Chapter: Psychology: Motivation and Emotion

Emotion Regulation

Emotion Regulation

Plainly,

then, emotions have many functions—preparing the body for action, directing our

attention, facilitating social interactions, and more (Levenson, 1999). But

emotions can hurt us, too, if they happen at the wrong time or at the wrong

intensity level. Indeed, inappropriate emotional responses are involved in many

forms of psychopathology and even many

forms of physical illness.

For

all these reasons, humans need to experience their emotions, but they also

some-times need to regulate their emotions. Emotion regulation means influencing which emotions we have, when

we have them, and how we experience or express them (J. J. Gross, 1998b, 2007).

Emotion regulation may involve decreasing, increasing, or simply maintaining

experiential, behavioral, or physiological aspects of emotion, depending on our

goals. The most common forms of emotion regulation, though, involve efforts at

decreasing the experience or behavior associated with anxiety, sadness, and

anger (J. J. Gross, Richards, & John, 2006).

TWO FORMS OF EMOTION REGULATION

Two

forms of emotion regulation have received the most attention (J. J. Gross,

2001). The first is called cognitive reappraisal,

which occurs when someone tries to decrease her emotional response by changing

the meaning a situation has. For example, instead of thinking of a job

interview as a matter of life or death, a person might think about the

interview as a chance to learn more about the company, to see whether it would

be fun to work there. The second kind of emotion regulation is called suppression, which occurs when someone

tries to decrease the emotion he shows on his face or in his behavior. For

example, instead of bursting into tears upon receiving disappointing news, a

person might bite his lip and put on a brave face.

While both strategies can decrease emotional behavior, reap- praisal seems to be a more effective way to regulate emotions. In part, this is because someone who suppresses an emotional reac- tion might block the display of emotion but does not make the feel- ings go away (J. J. Gross & Levenson, 1997). In fact, physiologically, suppression leads to even greater sympathetic nervous system acti- vation, presumably because the individual must exert herself to keep her emotions from showing (J. J. Gross, 1998a). There is also a cognitive cost to suppression. When participants in an experiment were asked about material that had been presented while they were trying to suppress their emotions, they made more errors than they did when they had not been suppressing their emo-tions (Richards & Gross, 2000). Indeed, when asked to suppress their emotions, par-ticipants performed as badly on later memory tasks as participants who had been encouraged not to pay attention at all to the material that was being presented (Richards & Gross, 2006).

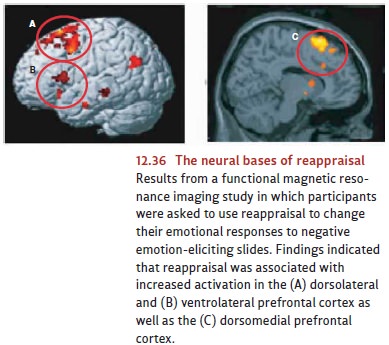

In

contrast, reappraisal can make one feel better, and it does not have cognitive

or physiological costs (J. J. Gross, 1998a). In one study, researchers showed

participants neutral or negative emotion-eliciting slides during an fMRI study

(Ochsner et al., 2004; Figure 12.36). In the critical conditions, participants

were asked either to view the nega-tive emotion-eliciting slides or to

reappraise them by altering their meaning. For exam-ple, a participant might

see a picture of women crying in front of a church. Instead of thinking of a

funeral scene, the participant might try to think of it as a wedding scene that

brought the woman to tears of joy. The reappraisal had many effects.

Participants reported feeling less negative emotion when reappraising than they

did when just watch-ing the negative slides. Reappraisal also activated the

prefrontal regions in the brain, which are associated with other kinds of

self-regulation, and decreased activation in the amygdala and other brain

regions associated with negative emotion.

The

key message from these studies is that different forms of emotion regulation

have quite different consequences. This is not to say one should always

reappraise or never suppress. Both processes have their place. But it is

becoming clear that compared with keeping a stiff upper lip by means of

suppression, reappraisal is generally more adaptive.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF EMOTION REGULATION

How

do the emotion regulation skills that are so necessary in adulthood develop? We

know that children respond emotionally from an early age. From birth, babies

cry when they are distressed and cease crying when they are comforted. Newborns

and young infants also display facial responses when they are interested,

distressed, disgusted, or contented (Izard et al., 1995; Figure 12.37). Smiles

appear—to parents’ delight—a bit

later.

Fleeting smiles are visible in 1-month-old infants; smiles directed toward

other people appear when most infants are 2 or 3 months old. Fear arrives later

still. The first clear signs of fear typically emerge only when the child is 6

or 7 months old (Witherington, Campos, & Hertenstein, 2001).

Of

course, very young infants show little ability to control their emotions, and

so it is up to the caregiver to soothe, distract, or reassure them. Soon,

though, infants start showing the rudiments of regulation, so that

6-month-olds, for example, are likely to turn their bodies away from unpleasant

stimuli (Mangelsdorf, Shapiro, & Marzolf, 1995). By their first birthday,

infants regulate their feelings by rocking themselves, or chewing on objects,

or clinging tightly to some beloved toy or blanket.

Children

also begin to use display rules—and so begin expressing their emotions in a

socially acceptable way—at an early age, so that, for example, 11-month-old

American infants are more expressive of their feelings than Chinese babies

(Freedman & Freedman, 1969). However, their self-control is limited at this

early age, and clear adherence to display rules is usually not evident until

the child is age 3 or so (Lewis, Stanger, & Sullivan, 1989)—and even then,

children’s attempts at disguising their emo-tions are often unsuccessful. It is

clear, though, that children learn relatively early the value of managing one’s

expressions—sometimes to gain the response one wants from others, sometimes to

protect others, and sometimes to deceive them (Vrij, 2002).

The

real progress in emotion regulation, however, comes later, when the child is

age 4 or 5. By that age, children seem to understand, for example, that they

can diminish their fear by fleeing from, or removing, the scary object; they

learn that they can dimin-ish their sadness by seeking out an adult’s aid or by

reassuring self-talk (Harris, Guz, Lipian, & Man-Shu, 1985; Lagattuta,

Wellman, & Flavell, 1997). These early skills are limited, but gradually

grow and strengthen. Where do these skills come from?

Part

of the answer lies in the child’s conversational experience, because children’s

efforts in emotion regulation are influenced by the examples they have observed

and the instructions they have received (R. A. Thompson, 1994, 1998). In fact,

these conver-sations convey a range of strategies to children, including

distraction (“Try thinking of something happy”), compensation (“Why don’t we

get ice cream after the appointment with the doctor?”), and reappraisal

(“Dumbledore didn’t really die; it’s just pretend”). Conversations with

children about emotion also convey when emotions should or should not be

expressed, and the consequences of expressing or not expressing them

(Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998).

Related Topics