Chapter: Psychology: Motivation and Emotion

The Diversity of Motives

THE DIVERSITY

OF

MOTIVES

Some

of the wide range of motives we have discussed are well described in drive

terms. Other motives seem to have both a prominent avoidance (drive-reduction)

component and an approach component. As this list of motives grows, however,

one pressing ques-tion is how to organize the many motives that energize and

direct our behavior.

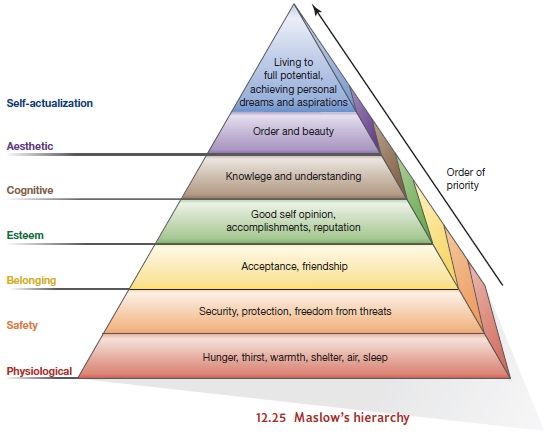

Maslow and the Hierarchy of Needs

One

approach was suggested by Maslow, who described a hierarchy of needs in which the lower-order physiological needs are

at the bottom of the hierarchy, safety needs are further up, the need for

belonging is still higher, and the desire for esteem is higher

yet. Higher still, toward the

top of the

hierarchy, is the striving

for self- actualization—the desire to realize oneself to the fullest

(Figure 12.25).

Maslow

believed that people will strive for higher-order needs (e.g., self-esteem or

artis- tic achievement) only when lower-order needs (e.g., hunger) are

satisfied. By and large this is plausible enough; the urge to write poetry gen-

erally takes a back seat if one has not eaten for days. But

as Maslow pointed

out, there are exceptions. Some

artists starve rather

than give up their

poetry or their

painting, and some martyrs

proclaim their faith

regardless of pain or

suffering. But to

the extent that Maslow’s

assumption holds, a motive

toward the top of his hierarchy—such as

the drive toward self-actualization—will become

pri- mary only when all other needs beneath it are satisfied.

The Twin Masters: Pain and Pleasure

A

second approach to organizing our many motives, rather than listing them

hierarchi-cally as Maslow did, is to dig deeper and look for a few common

principles that under-lie our diverse motives. This approach leads us to

consider the twin masters of pain and pleasure which may be said to govern much

of our behavior.

THE AVOIDANCE OF PAIN

What

do being too hot (or cold), being famished, being frightened, and being

sexually frustrated have in common? We sometimes speak of each as involving its

own type of pain, although this usage

of the word might seem metaphorical. After all, in discussing a specific

sensation typically associated with tissue injury or irritation. It turns out,

though, that there is no metaphor here, and various states of discomfort do

involve mechanisms overlapping with those associated with, say, stepping on a

nail or bumping your head.

As

we saw, pain is a “general purpose” signal that all is not well. There are

multiple pain pathways, including a fast pain pathway that detects localized

pain and relays this information quickly via the thalamus to the cortex using

thick, myelinated fibers, as well as a slow pain pathway that carries less

localized sensations of burning or aching via the thalamus to subcortical brain

structures such as the amygdala using thinner unmyelinated fibers. These

pathways differ in important ways, but they both carry information that allows

us to distinguish different types of painful stimulation, and an awareness of

these differences is important, because this is what allows us to know what

steps to take to decrease the pain we are feeling.

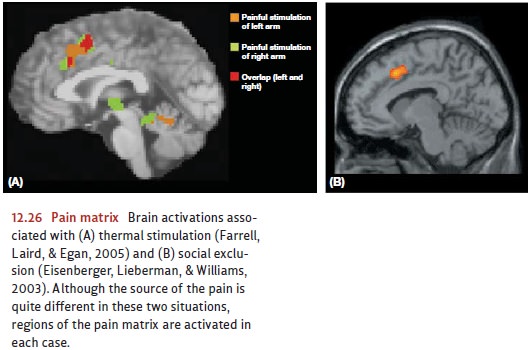

At

the same time, researchers are beginning to appreciate that many different

types of stimulation activate a common brain network, referred to as the pain matrix. The pain matrix consists

of a distributed set of regions including the thalamus and the anterior cingulate

cortex. The physical pain of accidentally touching a hot stove acti-vates this

matrix, but so does the psychological pain that comes with being socially

snubbed, and this is what tells us that these various forms of discomfort

really do have elements in common—both functionally and neurally. Figure 12.26

shows the similar brain activations associated with thermal stimulation (Panel

A) as well as social exclu-sion (Panel B).

What’s

important here is to appreciate that pain in all of its forms has both a

specific and a general motivational role. Some pain signals provide specific

information about what is happening (there’s a burning sensation in my right

hand) and motivate a specific response (I need to move my hand away from the

stove). Other pain signals alert us to different, broader kinds of problems,

and suggest different types of responses, such as a departure from a socially

awkward situation.

This

overlap among very different types of “pain” is important for another reason.

It provides a “common currency” in which to express a wide range of undesirable

states. The function of this common currency becomes clear when we realize that

many motives typically operate at a time, ranging from tight shoes to thirst to

fatigue. In such settings, the generic aspect of pain allows us to decide which

of these quite different states to attend to now and which can be handled

later.

THE PURSUIT OF PLEASURE

Efforts

to avoid or reduce painful states of tension govern many of our behaviors.

However, as Maslow pointed out, reducing these states is not our only motive.

We also have positive goals, and seek out pleasurable states.

Such

states involve incentives, or positive goals that we seek to obtain. We

therefore do not just feel “pushed” by an internal state of tension. Instead,

the incentive seems to “pull” us in a certain direction. As we have seen,

though, these incentives come in different types. Some are an inherent part of

the activity or object to which we are drawn (e.g., playing the guitar because the

experience itself is fun). In such

cases, the activity or object is said to be intrinsically rewarding. Other incentives, by contrast, are not an

integral part of the activity or object to which we are drawn, but are instead

arti-ficially associated with it (e.g., getting paid for painting a picture).

In this case, we say that the activity or object is extrinsically rewarding.

Historically,

research on incentives has focused on external determinants of behavior— the

specific rewards available to us and their influence on our behavior. It is

becoming clear, however, that internal states of pleasure have a role in

supporting incentives that parallels the role of the internal states of pain in

supporting drives. This realization has directed researchers’ attention to

examining two different aspects of our responses to rewarding stimuli, namely,

wanting and liking.

Wanting refers to the organism’s

motivation to obtain a reward and is measured bythe amount of effort the

organism will exert to obtain it. Because wanting is defined behaviorally, it

can be assessed in any organism whose behavior we can measure. With rats, we

can ask how many times they will press the bar to dispense a food pellet. In a

similar fashion, we can see how hard people will work to obtain a reward: If

you want brownies, do you want them badly enough to go through the trouble of

making them? And if you don’t have the ingredients, do you want brownies badly

enough to first go shopping and then make them?

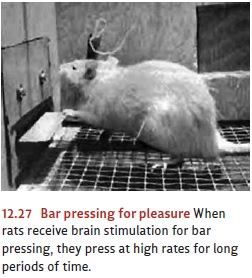

In

contrast to wanting, liking refers

to the pleasure that follows receiving the reward, like the pleasure deriving

from the luscious taste of the warm brownies. We all know the sensation of

liking, but unlike wanting, liking is difficult to define behaviorally.

However, we can explore the neural basis of this experience. Research on this

point dates back more than half a century to work by Olds and Milner, who

electrically stimulated rats’ brains in different regions. They found that

stimulation in some regions led rats to engage in behaviors such as returning

repeatedly to the location at which they were ini-tially stimulated, seemingly

in an attempt to repeat the stimulation. To understand this phenomenon, Olds

and Milner made the brain stimulation contingent upon bar presses, and found

that rats would bar press at very high rates for long periods of time, and to

the exclusion of other activities, in order to obtain this stimulation (Figure

12.27). One par-ticularly important spot for this effect—in rats and

humans—appears to be the medial forebrain bundle, a nerve tract consisting of

neurons with cell bodies in the midbrain which synapse in the nucleus accumbens (in the striatum).

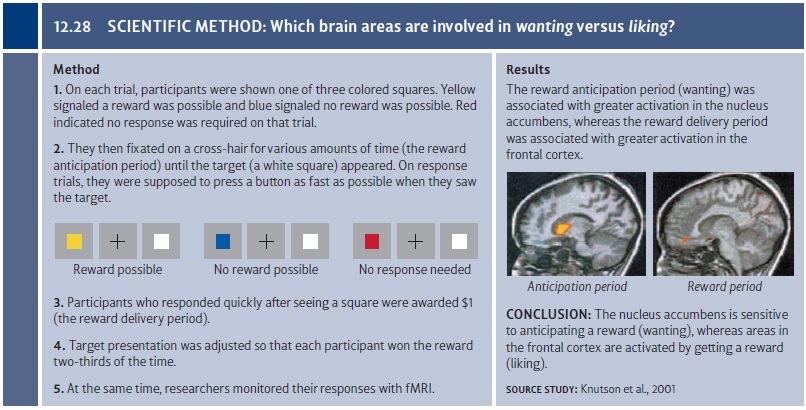

Apparently,

stimulation in this brain area is strongly rewarding—but why? Is this area involved in wanting

or in liking? Modern neuroimaging

research suggests an answer, and indicates that different brain regions are

engaged by reward anticipation (wanting) and reward delivery (liking) (Schultz,

Tremblay, & Hollerman, 2000). In particular, regions in the frontal cortex

are activated by liking, whereas the nucleus accumbens is especially sensitive

to wanting. In one of the first studies to demonstrate this dissociation in

humans, Knutson and colleagues used fMRI during a task in which participants

were shown various types of cues and were asked to respond to a target

(Knutson, Fong, Adams, Varner, & Hommer, 2001). If participants responded

quickly enough, they were able to win one dollar, and target presentation was

adjusted for each individual so that each participant succeeded approximately

two-thirds of the time. As shown in Figure 12.28, the period of anticipation and

wanting was associated with greater activation in the nucleus accumbens,

whereas the period of liking the reward was associated with activation in the

frontal cortex. These activation patterns suggest that the processes of wanting and liking have separate bases in the brain.

Additional

evidence that wanting and liking depend on separable brain systems comes from

studies of the neurotransmitters that underlie reward processing. When

animals

are trained to bar press for a reward, their neurons release dopamine into the

nucleus accumbens neurons during anticipation but not during receipt of reward

(Phillips et al., 2003). When dopamine antagonists are introduced, which

interfere with the effects of dopamine, the animals will continue to engage in

incentive-driven behavior for a time, but they will not work to receive rewards

that are not present (Berridge & Robinson, 2003). These and other findings

suggest that dopamine release plays a central role in wanting. Complementary

studies have examined the neurotrans-mitters that are responsible for liking.

These studies suggest that endorphins are released into the nucleus accumbens

when rewards are delivered. When endorphin antagonists are administered (in humans),

these appear to diminish the subjective pleasure associated with consuming the

rewards (Yeomans & Gray, 1996).

Related Topics