Chapter: Psychology: Motivation and Emotion

Motivational States

MOTIVATIONAL STATES

Questions

about why we act in a certain way, or why we feel as we do, can be answered in

various ways. Some answers emphasize what we referred as ultimate causes,

including the powerful influence, over thousands and thousands of years, of

natural selection. This reflects the key fact that, as we saw in that earlier,

evo-lutionary forces have shaped not only our physical features but also our

psychological features.

Other

answers about why we act or feel as we do focus on causes that are specific to

the individual, but are nonetheless fairly remote from the present situation.

For exam-ple, why do some people prefer to take psychology courses, while

others prefer astro-physics? Here, the cause may be rooted in the person’s

childhood. Perhaps the person happened to experience unusual events, and this

triggered a lifelong interest in human behavior and mental processes. Or

perhaps the person is seeking to distance herself from her parents, and her

parents have always been skeptical about psychology. In either case, these

decades-past circumstances are now shaping the person’s behavior.

Important

as these remote causes are, they do not tell us everything we need to know.

After all, we do not eat because we think, “Natural selection requires that I

eat.” Likewise, we usually do not choose courses by reasoning through “Will

this selection help me to be different from my mother?” We need to ask,

therefore, what the bridge is between remote causes, on the one side, and

actual behaviors, on the other. What are the more immediate causes of our

behavior?

The

answer to this question can take many forms, because, quite simply, we are

moti-vated by different forces in different circumstances. Early theorists

emphasized the bio-logical roots of our motivation, describing our diverse

motivational states as all arising from genetically endowed instincts. Early theorists such as

William James (1890) thought humans were impelled by innate motives that were

activated by features of the environment, much as spiders spin webs and birds

build nests (Figure 12.1). Following James’s lead, early psychologists drew up

lists of instincts that they believed governed human behavior. Thus, for

example, William McDougal (1923) asserted that humans have 13 instincts,

including parenting, food seeking, repulsion, curiosity, and gregari-ousness

(i.e., a tendency to seek out social contact).

Unfortunately,

different theorists came up with quite different lists of instincts, and in

1924, sociologist Luther Bernard counted over 5,000 instincts that had been

proposed by one scholar or another. This meant that instinct theory was—at

best— inelegant, but, worse, commentators increasingly wondered what work the

theory was actually doing. What did it mean to “explain” the impulse to parent

one’s children by postulating a “parenting instinct”? We could, on this model,

“explain” why people vote by asserting that there is a “self-governance

instinct,” and explain why they go shop-ping by asserting a “shopping

instinct.” In each case, our “explanation” merely provides a new bit of jargon

that offers us no new information.

A different conception of motivation turns out to be more productive. More than a century ago, the French physiologist Claude Bernard (1813–1878) noted that every organism has both an external environment and an internal one. The external environment includes the other creatures that the organism interacts with, and also the organism’s physical surrounding—the temperature, the topography, the avail-ability of shelter and water, and so on. But the organism’s internal environment is just as important, and includes the concentrations of various salts in the body’s flu-ids, the dissolved oxygen levels and pH, and the quantities of nutrients like glucose, the sugar that most organisms use as their body’s main fuel.

Moreover,

Bernard noted that even with large-scale fluctuations in the outside

environment, there is a striking constancy in the organism’s internal state.

All of the internal conditions we just listed fluctuate only within narrow

limits, and, indeed, they must stay within these limits, because otherwise the

organism is at severe risk. Apparently, therefore, the organism is capable of

making substantial changes in order to compensate for the variations it

encounters in the world.

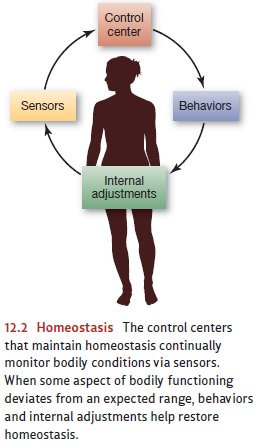

The

maintenance of this internal equilibrium involves a process known as homeostasis (Figure 12.2). Homeostasis

involves many mechanisms, including inter-nal adjustments (e.g., mechanisms in

the kidneys that control the concentration of sodium in the bloodstream), and

also a diverse set of behaviors (e.g., eating when you are low on calories,

seeking shelter when you are cold), and this returns us to our discussion of

motives. Deviations from homeostasis can create an internal state of

bio-logical and psychological tension called a drive—a drive to eat, a drive to sleep, and so on. The resulting

behavior then reduces the drive and thus returns us to equilibrium.

Drive-reduction

allows us to explain many of our motivated behaviors—including behaviors

essential for our survival. As we will see later, though, some behaviors cannot

be explained in this fashion, and so we will need a broader concep-tion of

motivation before we are through. Even so, drive-reduction plays a central role

in governing the behavior of humans and many other species.

Related Topics