Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Eye and Vision Disorders

Retinal Detachment - Retinal Disorders

Retinal Disorders

Although the retina is composed of multiple

microscopic layers, the two innermost layers, the sensory retina and the

retinal pig-ment epithelium (RPE), are the most relevant to common retinal

disorders. Just as the film in a camera captures an image, so does the retina,

the neural tissue of the eye. The rods and cones, the photoreceptor cells, are

found in the sensory layer of the retina. Beneath the sensory layer lies the

RPE, the pigmented layer. When the rods and cones are stimulated by light, an

electrical impulse is generated, and the image is transmitted to the brain.

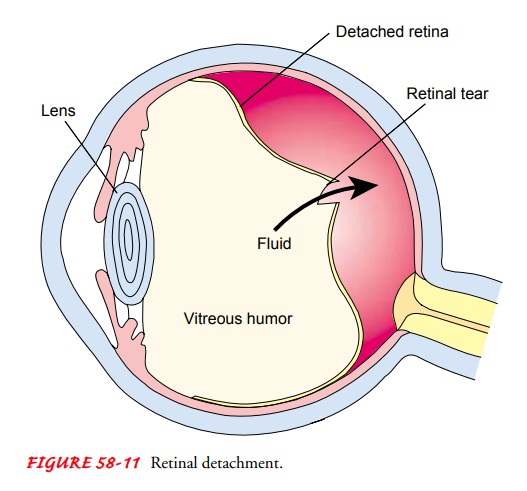

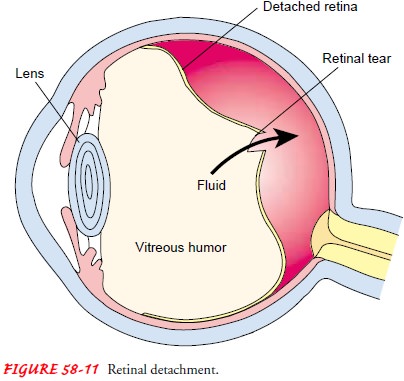

RETINAL DETACHMENT

Retinal

detachment refers to the separation of the RPE from the sensory layer. The four

types of retinal detachment are rheg-matogenous, traction, a combination of

rhegmatogenous and traction, and exudative. Rhegmatogenous

detachment is the most common form. In this condition, a hole or tear

develops in the sen-sory retina, allowing some of the liquid vitreous to seep

through the sensory retina and detach it from the RPE (Fig. 58-11). People at

risk for this type of detachment include those with high myopia or aphakia after cataract surgery. Trauma

may also play a role in rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Between 5% and 10%

of all rhegmatogenous retinal detachments are associated with proliferative

retinopathy, a retinopathy associated with dia-betic neovascularization.

Tension,

or a pulling force, is responsible for traction

retinaldetachment. An ophthalmologist must ascertain all of the areas

ofretinal break and identify and release the scars or bands of fibrous material

providing traction on the retina. Generally, patients with this condition have

developed fibrous scar tissue from conditions such as diabetic retinopathy,

vitreous hemorrhage, or the retinopa-thy of prematurity. The hemorrhages and

fibrous proliferation as-sociated with these conditions exert a pulling force

on the delicate retina.

Patients

can have both rhegmatogenous and traction retinal detachment. Exudative retinal detachments are the

result of the production of a serous fluid under the retina from the choroid.

Conditions such as uveitis and macular degeneration may cause the production of

this serous fluid.

Clinical Manifestations

Patients

may report the sensation of a shade or curtain coming across the vision of one

eye, cobwebs, bright flashing lights, or the sudden onset of a great number of

floaters. Patients do not com-plain of pain.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

After visual acuity is determined, the patient must have a dilated fundus examination using an indirect ophthalmoscope and a Goldmann three-mirror examination. This examination is detailed and prolonged, and it can be very uncomfortable for the patient. Many patients describe this as looking directly into the sun. All retinal breaks, all fibrous bands that may be causing traction on the retina, and all degenerative changes must be identified. A de-tailed retinal drawing is made by the ophthalmologist.

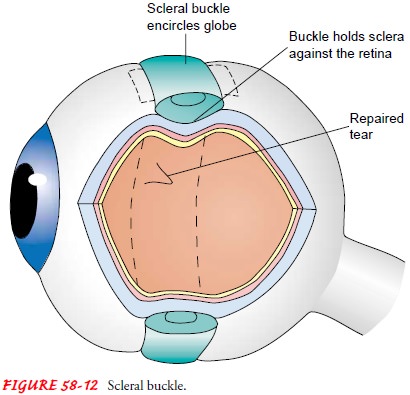

Surgical Management

In

rhegmatogenous detachment, an attempt is made to reattach the sensory retina to

the RPE surgically. The retinal surgeon com-presses the sclera (often with a

scleral buckle or a silicone band; Fig. 58-12) to indent the scleral wall from

the outside of the eye and bring the two retinal layers in contact with each

other. Gas bubbles, silicone oil, or perfluorocarbon and liquids may also be

injected into the vitreous cavity to help push the sensory retina up against

the RPE. Argon laser photocoagulation or cryotherapy is also used to

“spot-weld” small holes.

In traction retinal detachment, a vitrectomy is

performed. A vit-rectomy is an intraocular procedure in which 1- to 4-mm

incisions are made at the pans plana. One incision allows the introduction of a

light source (ie, endoilluminator), and another incision serves as the portal

for the vitrectomy instrument. The surgeon dissects preretinal membranes under

direct visualization while the retina is stabilized by an intraoperative

vitreous substitute. Technologic advances, including the use of operating

microscopes, micro-instrumentation, irrigating contact lenses, and instruments

that combine vitreous cutting, aspiration, and illumination capabili-ties into

one device, have allowed tremendous progress in vitre-oretinal surgery. The

techniques of vitreoretinal surgery can be used in various procedures,

including the removal of foreign bodies, vitreous opacities such as blood, and

dislocated lenses. Traction on the retina may be relieved through vitrectomy

and may be combined with scleral buckling to repair retinal breaks. Treatment

of macular holes includes vitrectomy, laser photo-coagulation, air-fluid-gas

exchanges, and the use of growth factor.

Nursing Management

For the most part, nursing interventions consist of educating the patient and providing supportive care.

PROMOTING COMFORT

If

gas tamponade is used to flatten the retina, the patient may have to be

specially positioned to make the gas bubble float into the best position. Some

patients must lie face down or on their side for days. Patients and family

members should be made aware of these special needs beforehand, so that the

patient can be made as comfortable as possible.

TEACHING ABOUT COMPLICATIONS

In many cases, vitreoretinal procedures are

performed on an out-patient basis, and the patient is seen the next day for a

follow-up examination and closely monitored thereafter as required.

Post-operative complications in these patients may include increased IOP,

endophthalmitis, development of other retinal detach-ments, development of

cataracts, and loss of turgor of the eye. Pa-tients must be taught the signs

and symptoms of complications, particularly of increasing IOP and postoperative

infection.

Related Topics