Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Eye and Vision Disorders

Impaired Vision: Refractive Errors, Low Vision and Blindness

Impaired Vision

REFRACTIVE ERRORS

In refractive errors, vision is impaired because a

shortened or elongated eyeball prevents light rays from focusing sharply on the

retina. Blurred vision from refractive error can be corrected with eyeglasses

or contact lenses. The appropriate eyeglass or contact lens is determined by refraction. Refraction ophthalmology

con-sists of placing various types of lenses in front of the patient’s eyes to

determine which lens best improves the patient’s vision.

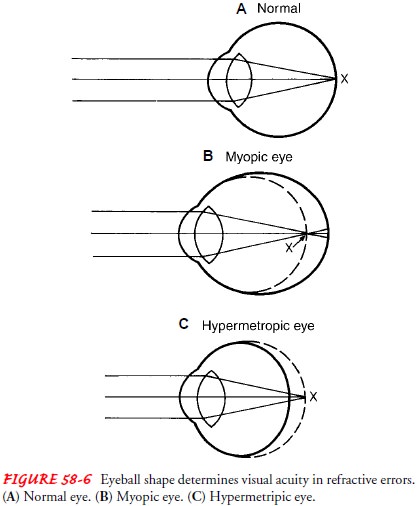

The depth of the eyeball is important in

determining refractive error (Fig. 58-6). Patients for whom the visual image

focuses pre-cisely on the macula and who do not need eyeglasses or contact

lenses are said to have emmetropia

(normal vision). People who have myopia

are said to be nearsighted. They have deeper eye-balls; the distant visual

image focuses in front of, or short of, the retina. Myopic people experience

blurred distance vision. When people have a shorter depth to their eyes, the

visual image focuses beyond the retina; the eyes are shallower and are called

hyperopic. People with hyperopia are

farsighted. These patients experience near vision blurriness, whereas their

distance vision is excellent.

Another important cause of refractive error is astigmatism, an irregularity in the curve of the cornea. Because astigmatism causes a distortion of the visual image, acuity of distance and near vision can be decreased. Eyeglasses with a cylinder correction or rigid or soft toric contact lenses are appropriate for these patients.

LOW VISION AND BLINDNESS

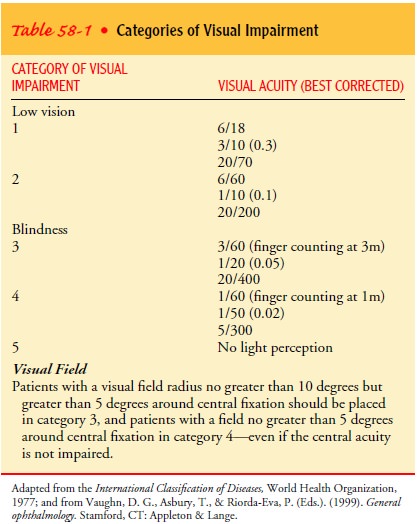

Low

vision is a general term

describing visual impairment that re-quires patients to use devices and

strategies in addition to correc-tive lenses to perform visual tasks. Low

vision is defined as a best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 20/70 to 20/200

(Table 58-1).

Blindness is

defined as a BCVA of 20/400 to no light per-ception. The clinical definition of

absolute blindness is the ab-sence of light perception. Legal blindness is a

condition of impaired vision in which an individual has a BCVA that does not

exceed 20/200 in the better eye or whose widest visual field di-ameter is 20

degrees or less. This definition does not equate with functional ability, nor

does it classify the degrees of visual im-pairment. Legal blindness ranges from

an inability to perceive light to having some vision remaining. An individual

who meets the criteria for legal blindness may obtain government financial

assistance. There are more than 1,046,000 legally blind Ameri-cans who are 40

years of age or older. African Americans have a higher rate of blindness than

do Caucasians (Preshel & Prevent Blindness America, 2002).

Impaired vision is accompanied by difficulty in performing functional activities. Individuals with visual acuity of 20/80 to 20/100 with a visual field restriction of 60 degrees to greater than 20 degrees can read at a nearly normal level with optical aids. Their visual orientation is near normal but requires increased scanning of the environment (ie, systematic use of head and eye movements). In a visual acuity range of 20/200 to 20/400 with a 20-degree to greater than 10-degree visual field restriction, the individual can read slowly with optical aids.

His or her visual orientation

is slow, with constant scanning of the environment; individuals in this

category have travel vision. Individuals with hand motion vision or no vision

may benefit from the use of mo-bility devices (eg, cane, guide dog) and should

be encouraged to learn Braille and to use computer aids.

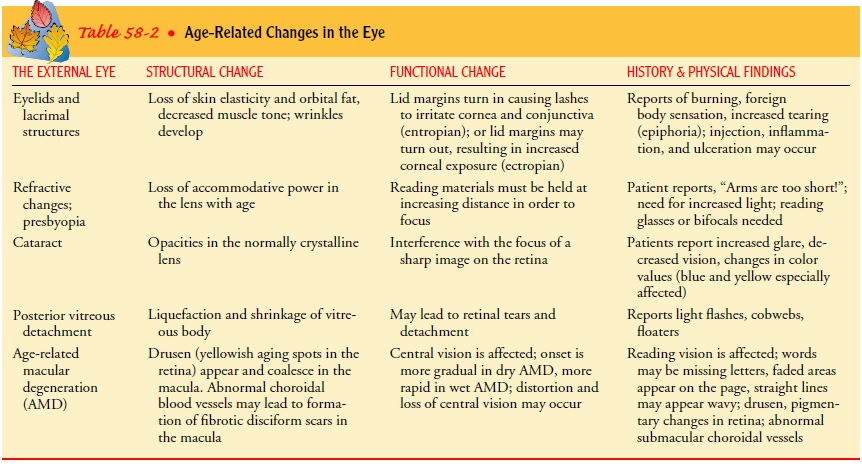

The

most common causes of blindness and visual impairment among adults 40 years of

age or older are diabetic retinopathy, macular degeneration, glaucoma, and

cataracts, (Preshel & Pre-vent Blindness America, 2002). Macular

degeneration is more prevalent among Caucasians, whereas glaucoma is more

preva-lent among African Americans. Age-related changes in the eye are

described in Table 58-2.

Low-Vision Assessment

The assessment of low vision includes a thorough

history and the examination of distance and near visual acuity, visual field,

contrast sensitivity, glare, color perception, and refraction. Specially

de-signed, low-vision visual acuity charts are used to evaluate patients.

PATIENT INTERVIEW

During history taking, the cause and duration of

the patient’s vi-sual impairment are identified. Patients with retinitis

pigmentosa, for example, have a genetic abnormality. Patients with diabetic macular

edema typically have fluctuating visual acuity. Patients with macular

degeneration have central acuity problems. Central acuity problems cause

difficulty in performing activities that re-quire finer vision, such as

reading. People with peripheral field defects have more difficulties with

mobility. The patient’s cus-tomary activities of daily living, medication

regimen, habits (eg, smoking), acceptance of the physical limitations brought

about by the visual impairment, and realistic expectations of low-vision aids

must also be identified. These aspects of the patient’s activi-ties are

important indicators for planning care that will include guidelines for safety

and referrals to social services.

ASSESSMENT

Contrast-sensitivity

testing measures visual acuity in different de-grees of contrast. The initial

test may take the form of simply turning on the lights while testing the

distance acuity. If the pa-tient can read better with the lights on, the

patient can benefit from magnification. Glare testing enables the examiner to

obtain a more realistic evaluation of the patient’s ability to function in his

or her environment. Glare can reduce a person’s ability to see, especially in

patients with cataracts. Devices that test glare, such as the Brightness Acuity

Tester, produce three degrees of bright light to create a dazzle effect while

the patient is viewing a target, such as Snellen letters on the wall. The

lights have been calibrated to imitate certain objects that create glare, such

as the brightness of a car’s headlights at night.

Medical Management

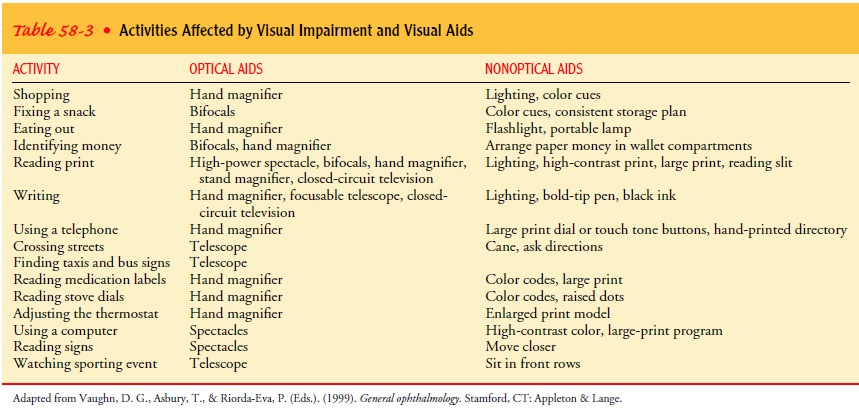

Managing low vision involves magnification and

image enhance-ment through the use of low-vision aids and strategies and

through referrals to social services and community agencies serv-ing the

visually impaired. The goals are to enhance visual func-tion and assist

patients with low vision to perform customary activities. Low-vision aids

include optical and nonoptical devices (Table 58-3). The optical devices

include convex lens aids, such as magnifiers and spectacles; telescopic

devices; anti-reflective lenses that diminish glare; and electronic reading

systems, such as closed-circuit television and computers with large print.

Contin-uing advances in computer software provide very useful products for

patients with low vision. Scanners teamed with the appro-priate software enable

the user to scan printed data into the computer and have it read by computer

voice or to increase the magnification for reading. Magnifiers can be hand-held

or at-tached to a stand with or without illumination. Telescopic de-vices can

be spectacle telescopes or clip-on or hand-held loupes.

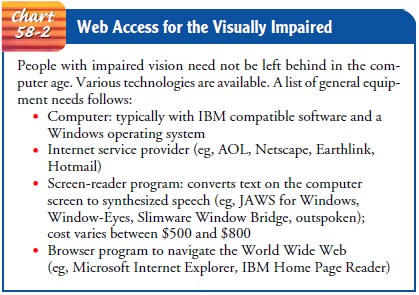

Nonoptical aids include large-print publications and a variety of writing aids. The Internet continues to expand, and a tele phone system has been developed that allows access to the Inter-net and e-mail using voice commands (see Chart 58-2).

Strategies that enhance the performance of visual tasks in-clude modification of body movements and illumination and training for independent living skills. Head movements and positions can be modified to place images in functional areas of the visual field. Illumination is an added feature in magnifiers. Adjusting the lighting helps with reading and other activities. Simple optical and nonoptical aids are available in low-vision clinics.

Referrals

to community agencies may be necessary for low-vision patients living alone who

are unable to self-administer their medications. Community agencies, such as

The Lighthouse National Center for Vision and Aging, offer services to

low-vision patients that include training in independent living skills and the

provision of occupational and recreational activities and a wide variety of

assistive devices for vision enhancement and orienta-tion and mobility.

VISION RESTORATION FOR THE BLIND

Ophthalmologists

have worked toward visual restoration for blind individuals for years, and

computer technology now pro-vides opportunities for restoring sight. For

example, a multiple-unit artificial retina chipset (MARC) has been devised for

implanting within the eye. The MARC can be enabled to receive signals from an

external camera mounted in a glasses frame. The acquired image is wirelessly

transmitted to the chip, which pro-vides a type of artificial vision and which,

with training, allows the patient to achieve some useful vision. Although the

device is still experimental, some work has been done with patients who have

lost vision from retinitis pigmentosa and age-related macu-lar degeneration

(Humayan et al., 1999).

Nursing Management

Coping

with blindness involves three types of adaptation: emo-tional, physical, and

social. The emotional adjustment to blind-ness or severe visual impairment

determines the success of the physical and social adjustments of the patient.

Successful emo-tional adjustment means acceptance of blindness or severe visual

impairment.

PROMOTING COPING EFFORTS

Effective coping may not occur until the patient

recognizes the permanence of the blindness. Clinging to false hopes of

regain-ing vision hampers effective adaptation to blindness. A newly blind

patient and his or her family members (especially those who live with the

patient) undergo the various steps of grieving: de-nial and shock, anger and

protest, restitution, loss resolution, and acceptance. The ability to accept

the changes that must come with visual loss and willingness to adapt to those

changes influence the successful rehabilitation of the patient who is blind.

Additional aspects to consider are value changes, independence–dependence

conflicts, coping with stigma, and learning to function in social settings

without visual cues and landmarks.

PROMOTING SPATIAL ORIENTATION AND MOBILITY

People

who are blind detect and incorporate less information about their environment

than do sighted people. The blind per-son relies on egocentric, sequential, and

positional information, which centers on the person and his or her relationship

to the ob-jects in the environment. For example, the topographic concepts of

front, back, left, right, above, and below and measures of dis-tances are most

useful in determining the exact position, se-quence, and location of objects in

relation to the person who is blind. Although their basis of information may be

different from that of sighted people, people who are blind can comprehend

spa-tial concepts.

The goal of orientation and mobility training is to

foster in-dependence in the environment. Training may be accomplished by using

auditory and tactile cues and by providing anticipatory information. Having a

concept of the spatial composition of the environment (ie, cognitive map)

enhances independence of those who are blind. Orientation and mobility training

programs are offered by community agencies serving the blind or visually

im-paired. Training includes using mobility devices for travel, the long cane,

electronic travel aids, dog guides, and orientation aids. The basic orientation

and mobility techniques used by a sighted person to assist a person who is

blind or visually impaired to am-bulate safely and efficiently are called

sighted-guide techniques.

Spatial Orientation and

Mobility in Institutional Settings.A blindor severely visually impaired patient requires strategies for

adapt-ing to the environment. The monocular postoperative patient whose

functioning eye is restricted by a surgical patch or by post-operative

inflammation requires early ambulation just like any postoperative patient. The

activities of daily living, such as walking to a chair from a bed, require

spatial concepts. The patient needs to know where he or she is in relation to

the rest of the room, to understand the changes that may occur, and how to

approach the desired location safely. This requires a collaborative effort

be-tween the patient and the nurse, who serves as the sighted guide.

Patients

whose visual impairment results from a chronic pro-gressive eye disorder, such

as glaucoma, have better cognitive mapping skills than the suddenly blinded

patient. They have de-veloped the use of spatial and topographic concepts early

and gradually; hence, remembering a room layout is easier for them. Suddenly

blinded patients have more difficulty in adjusting; and emotional and

behavioral issues of coping with blindness may hinder their learning. These

patients require intensive emotional support. The nurse must assess the degree

of physical assistance the patient with a visual deficit requires and

communicate this to other health care personnel.

The food tray’s composition is likened to the face

of a clock. For example, the main plate may be described as being at 12 o’clock

or the coffee cup at 3 o’clock. In the hospital, the bedside table and the call

button must always be within reach. The parts of the call button are explained,

and the patient is encouraged to touch and press the buttons or dials until the

activity is mastered. The patient must be familiarized with the location of the

telephone, water pitcher, and other objects on the bedside table. All articles

and furniture must be replaced in the same positions. Introducing oneself on

entering a patient’s room is always a polite gesture and helps in the

orientation of a blind patient.

The nurse should be aware of the importance of

technique in providing physical assistance, developing independence, and

en-suring safety. The readiness of the patient and his or her family to learn

must be assessed before initiating orientation and mobil-ity training.

Teaching Patients Self-Care.The nurse, social workers,

family,and others collaborate to assess the patient’s home condition and

support system. If available, a low-vision specialist should be con-sulted

before discharge, particularly for patients for whom iden-tifying and

administering medications pose problems. The level of visual acuity and patient

preference help to determine appro-priate interventions. For example, a plastic

pill container with di-viders that has been prefilled with a week’s supply of

medication can make medication administration easier for some patients, whereas

others may prefer to have medication bottles marked with textured paints. Many

patients require referral to social ser-vices. Patients with habits that may

jeopardize safety, such as smoking, need to be cautioned and assisted to make

their envi-ronment safe.

Community Programs and

Services.In the United States,

lawssuch as the Rehabilitation Act, the Civil Rights Act, and the Americans

With Disabilities Act support assistance of the blind. Governmental services

include income assistance through Social Security Disability Income and

Supplemental Security Income; health insurance through Medicaid and Medicare

programs; support services, such as vocational rehabilitation programs of-fered

by the Division of Blind Services; tax exemptions and tax deductions;

Department of Veterans Affairs programs for visually impaired veterans; and

U.S. Postal Service reduced postage for Braille materials and talking books.

Related Topics