Chapter: Biotechnology Applying the Genetic Revolution: RNA-Based Technologies

RNAi for Studying Mammalian Genes

RNAi

FOR STUDYING MAMMALIAN GENES

An important application for

RNAi is testing the individual roles of human proteins, which can reveal new

targets for curing diseases. Until recently, using RNAi to assess the function

of mammalian proteins was not possible. The application of dsRNA to cultured

mammalian cells or whole mice induces a potent antiviral response. Interferon

is produced, which triggered the cells to degrade all RNA transcripts and shut

down protein synthesis. Thus, the methods used in C. elegans and Drosophila

killed mammalian cells, and no alternatives were known until recently.

Recognizing that short interfering

RNA (siRNA) pieces mediated RNAi was the key to its application in mammalian

systems. Instead of using long dsRNA as in C. elegans and Drosophila, exposing

mammalian cells to dsRNA shorter than 30 nucleotides activated the mammalian

counterparts to Dicer and RISC. This in turn abolished expression of the target

mRNA. Such short dsRNA segments thus act as endogenously produced siRNA. As

described earlier, siRNAs made by Dicer are short double-stranded RNA about 21

to 23 base pairs in length. In addition, the siRNAs have a two-base 3′ overhang

that is more stable when it consists of two uracils. To study a particular

target mRNA in mammalian cells, chemically synthesized siRNAs with these

characteristics are designed to have the complementary sequence to the target.

Much like antisense oligonucleotides, these may have modifications to make them

more stable, such as methyl groups added to the 2′-OH of the ribose. The most important and the

most difficult aspect of in vitro

siRNA construction is determining an effective sequence. The sequence on the

target mRNA must be accessible to the siRNA, which may be challenging because

of RNA secondary structure. Many suitable siRNA are designed and synthesized,

and each is tested for activating RNAi. These siRNA are delivered to mammalian

cells much like antisense oligonucleotides, including transfection, liposomes,

and microinjection.

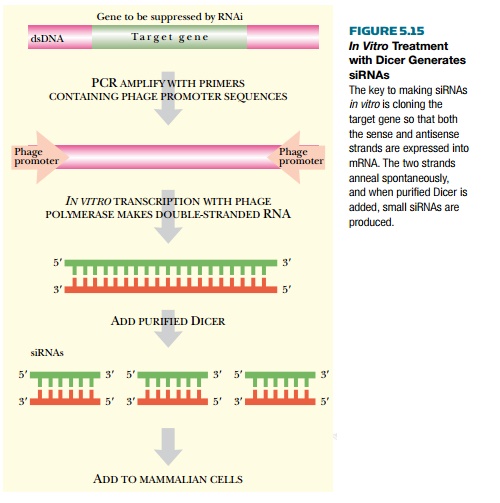

Rather than chemically

synthesizing siRNA, the target mRNA can be mixed with purified Dicer to cleave

the target mRNA into siRNA pieces (Fig. 5.15). Although the reaction occurs in

a tube, the purified Dicer can generate multiple siRNAs as it would in vivo. In order to create the target

mRNA, the chosen target gene is amplified with PCR using PCR primers that also

contain a promoter sequence for T7 RNA polymerase. The double-stranded DNA is

then converted into dsRNA by T7 RNA polymerase. The RNA pieces are allowed to

anneal spontaneously, and then they are mixed with purified Dicer, which

digests it into multiple different siRNAs. These are then transfected into

mammalian cells.

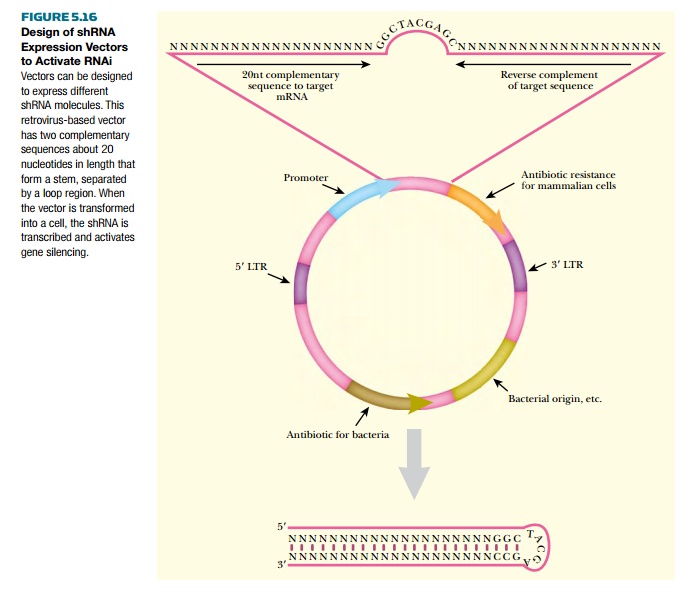

Additionally, mammalian cells can be induced to activate RNAi by expressing short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) that mimic the structure of microRNAs. A gene for the shRNA is constructed in a vector. The shRNA can be transcribed as two complementary strands by two different promoters facing in opposite directions, or simply made as one transcript with complementary ends interrupted by a sequence that forms a loop (Fig. 5.16). In both constructs, the complementary sequences come together to form a double-stranded RNA region. The most common promoter for expressing shRNA in vivo is the promoter for mammalian RNA polymerase III. (Note: This enzyme normally transcribes small noncoding RNAs.) RNA polymerase III starts transcription at a specific sequence and stops transcription when it encounters four to five consecutive thymidines. In addition, RNA polymerase III does not activate the enzymes that cap and add a poly(A) tail onto the transcript. This polymerase is precisely what is necessary to create an shRNA that mimics one found in eukaryotic cells.

Rather than designing the

shRNA constructs from scratch, another strategy uses preexisting microRNA.

First, the stem portion is

replaced with sequences that match the target mRNA. The newly designed microRNA

will trigger RNAi for the target mRNA rather than its endogenous target.

Vectors that express shRNAs

have some advantages over adding siRNA. When siRNA is added to mammalian

cultures, the effect is temporary. When the siRNA is gone, the effect ends

(unless heterochromatin formation was triggered, as seen in some organisms).

When an shRNA vector is transfected into a mammalian cell, the effect is more

sustained. The vector continues to produce shRNA for a considerable time. In

addition, expression of the shRNA may be controlled using promoters that are

inducible or tissue-specific. In a clinical setting, the ability to deliver the

siRNA only to those tissues that need it is crucial, and using a vector system

can accomplish this.

Related Topics