Chapter: Biochemistry: The Three-Dimensional Structure of Proteins

Prions and Disease

Prions and Disease

It has

been established that the causative agent of mad-cow disease (also known as

bovine spongiform encephalopathy or BSE), as well as the related diseases

scrapie in sheep, chronic wasting disease (CWD) in deer and elk, and human

spongiform encephalopathy (kuru and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease) in humans, is a

small (28-kDa) protein called a prion. (Note that biochemists tend to call the

unit of atomic mass the dalton,

abbreviated Da.) Prions are natural glycoproteins found in the cell membranes

of nerve tissue. Recently the prion protein has been found in the cell membrane

of hematopoietic stem cells, precursors to the cells of the bloodstream, and

there is some evidence that the prion helps guide cell maturation. The disease

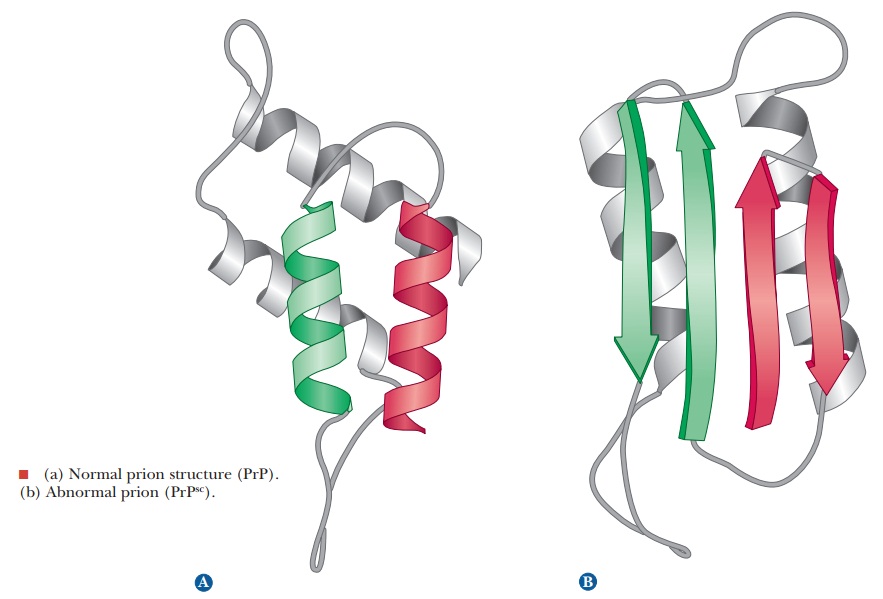

state comes about when the normal form of the prion protein, PrP (Figure a),

folds into an incorrect form called PrPsc (Figure

b). The abnormal form of the prion protein is able to convert other, normal

forms into abnormal forms. As was recently discovered, this change can be

propagated in nervous tissue. Scrapie had been known for years, but it had not

been known to cross species barriers. Then an outbreak of mad-cow disease was

shown to have followed the inclusion of sheep remains in cattle feed. It is now

known that eating tainted beef from animals with mad-cow disease can cause

spongiform encephalopathy, now known as new variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

(vCJD), in humans. The normal prions have a large percentage of α-helix, but

the abnormal forms have more β-pleated sheets. Notice that in this case the

same protein (a single, well-defined sequence) can exist in alternative forms.

These β-pleated sheets in the abnormal proteins interact between protein

molecules and form insoluble plaques, a fate also seen in Alzheimer’s disease.

Ingested abnormal prions use macrophages from the immune system to travel in

the body until they come in contact with nerve tissue. They can then propagate

up the nerves until they reach the brain.

This

mechanism was a subject of considerable controversy when it was first proposed.

A number of scientists expected that a slow-acting virus would be found to be

the ultimate cause of these neurological diseases. A susceptibility to these

diseases can be inherited, so some involvement of DNA (or RNA) was also

expected. Some went so far as to talk about “heresy” when Stanley Prusiner

received the 1997 Nobel Prize in medicine for his discovery of prions, but

substantial evidence shows that prions are themselves the infectious agent and

that no virus or bacteria are involved. It now appears that genes for

susceptibility to the incorrect form exist in all vertebrates, giving rise to

the observed pattern of disease transmission, but many individuals with the

genetic susceptibility never develop the disease if they do not come in contact

with abnormal prions from another source.

Further

studies have shown that all of the humans who showed symptoms of vCJD had the

same amino acid substitution in their prions, a substitution of a methionine at

position 129, now known to confer extreme sensitivity to the disease. While the

cases of vCJD are decreasing, some scientists warn that the lag between the

increase in mad-cow disease in Europe and the peak in human infections was too

short. They feel that the peak that is now declining represents the population

of humans that had the most severe mutation leading to the extreme sensitivity.

It is possible that other populations of humans have different muta-tions and

lesser sensitivities. These other populations could have longer incubation

times, so the vCJD threat may not be over yet.

Related Topics