Chapter: Biochemistry: The Three-Dimensional Structure of Proteins

Tertiary Structure of Proteins

Tertiary Structure of Proteins

The

tertiary structure of a protein is the three-dimensional arrangement of all the

atoms in the molecule. The conformations of the side chains and the positions

of any prosthetic groups are parts of the tertiary structure, as is the

arrangement of helical and pleated-sheet sections with respect to one another.

In a fibrous protein, the overall shape of which is a long rod, the secondary

structure also provides much of the information about the tertiary structure.

The helical backbone of the protein does not fold back on itself, and the only

important aspect of the tertiary structure that is not specified by the

secondary structure is the arrangement of the atoms of the side chains.

For a

globular protein, considerably more information is needed. It is neces-sary to

determine the way in which the helical and pleated-sheet sections fold back on each

other, in addition to the positions of the side-chain atoms and any prosthetic

groups. The interactions between the side chains play an important role in the

folding of proteins. The folding pattern frequently brings residues that are

separated in the amino acid sequence into proximity in the tertiary structure

of the native protein.

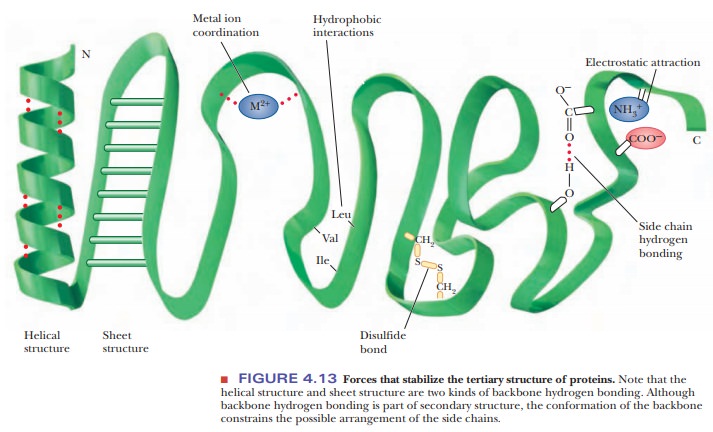

Forces Involved in Tertiary Structures

Many

types of forces and interactions play a role in holding a protein together in

its correct, native conformation. Some of these forces are covalent, but many

are not. The primary structure of a protein-the order of amino acids in the

polypeptide chain-depends on the formation of peptide bonds, which are

covalent. Higher-order levels of structure, such as the conformation of the

backbone (secondary structure) and the positions of all the atoms in the

protein (tertiary structure), depend on noncovalent interactions. If the

protein consists of several subunits, the interaction of the subunits also

depends on noncovalent interactions. Noncovalent stabilizing forces contribute

to the most stable structure for a given protein, the one with the lowest

energy.

Several

types of hydrogen bonding occur in proteins. Backbone hydrogen bonding is a major determinant of secondary

structure; hydrogen bonds between the

side chains of amino acids are also possible in proteins. Nonpolar

resi-dues tend to cluster together in the interior of protein molecules as a

result of hydrophobic interactions. Electrostatic attraction between

oppositely charged groups, which frequently occurs on the surface of the

molecule, results in such groups being close to one another. Several side

chains can be complexed to a single

metal ion. (Metal ions also occur in some prosthetic groups.)

In

addition to these noncovalent interactions, disulfide

bonds form covalent links between the side chains of cysteines. When such

bonds form, they restrict the folding patterns available to polypeptide chains.

There are specialized labo-ratory methods for determining the number and positions

of disulfide links in a given protein. Information about the locations of

disulfide links can then be combined with knowledge of the primary structure to

give the complete covalentstructure of

the protein. Note the subtle difference here: The primary structureis the order

of amino acids, whereas the complete covalent structure also speci-fies the

positions of the disulfide bonds (Figure 4.13).

Not

every protein necessarily exhibits all possible structural features of the

kinds just described. For instance, there are no disulfide bridges in myoglobin

and hemoglobin, which are oxygen-storage and transport proteins and classic

examples of protein structure, but they both contain Fe(II) ions as part of a

prosthetic group. In contrast, the enzymes trypsin and chymotrypsin do not

contain complexed metal ions, but they do have disulfide bridges. Hydrogen

bonds, electrostatic interactions, and hydrophobic interactions occur in most

proteins.

The three-dimensional conformation of a protein is the result of the inter-play of all the stabilizing forces. It is known, for example, that proline does not fit into an α-helix and that its presence can cause a polypeptide chain to turn a corner, ending an α-helical segment. The presence of proline is not, however, a requirement for a turn in a polypeptide chain. Other residues are rou-tinely encountered at bends in polypeptide chains. The segments of proteins at bends in the polypeptide chain and in other portions of the protein that are not involved in helical or pleated-sheet structures are frequently referred to as “random” or “random coil.” In reality, the forces that stabilize each protein are responsible for its conformation.

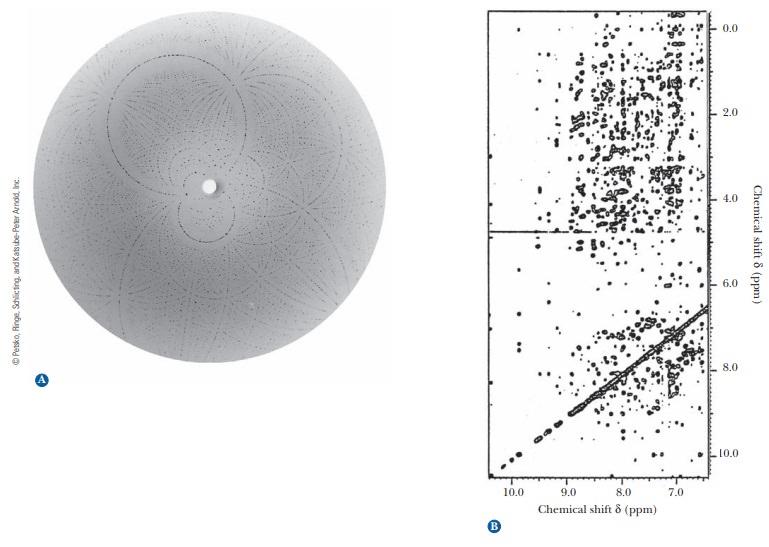

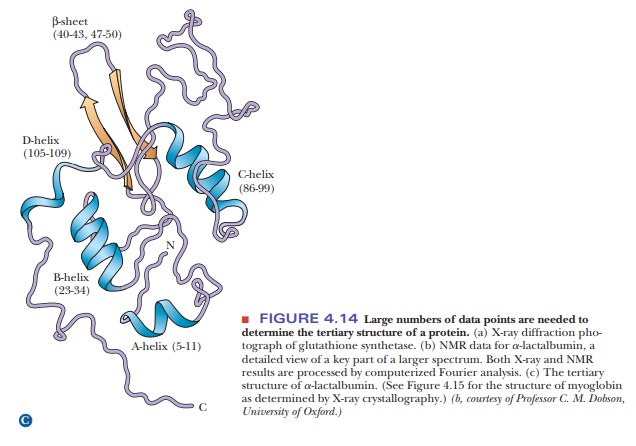

How can the three-dimensional structure of a protein be determined?

The

experimental technique used to determine the tertiary structure of a protein is

X-ray crystallography. Perfect

crystals of some proteins can be grown under carefully controlled conditions.

In such a crystal, all the individual protein molecules have the same

three-dimensional conformation and the same orientation. Crystals of this

quality can be formed only from proteins of very high purity, and it is not

possible to obtain a structure if the protein cannot be crystallized.

When a

suitably pure crystal is exposed to a beam of X rays, a diffraction pat-tern is produced on a photographic plate (Figure

4.14a) or a radiation counter.The pattern is produced when the electrons in

each atom in the molecule scat-ter the X rays. The number of electrons in the

atom determines the intensity of its scattering of X rays; heavier atoms scatter

more effectively than lighter atoms. The scattered X rays from the individual

atoms can reinforce each other or cancel each other (set up constructive or

destructive interference), giving rise to the characteristic pattern for each

type of molecule. A series of diffrac-tion patterns taken from several angles

contains the information needed to determine the tertiary structure. The

information is extracted from the diffrac-tion patterns through a mathematical

analysis known as a Fourier series.

Many thousands of such calculations are required to determine the structure of

a pro-tein, and even though they are performed by computer, the process is a

fairly long one. Improving the calculation procedure is a subject of active

research.

Another

technique that supplements the results of X-ray diffraction has come into wide

use in recent years. It is a form of nuclear

magnetic resonance(NMR) spectroscopy. In this particular application of

NMR, called2-D(twodimensional) NMR, large collections of data points

are subjected to computer analysis (Figure 4.14b). Like X-ray diffraction, this

method uses a Fourier series to analyze results. It is similar to X-ray

diffraction in other ways: It is a long pro-cess, and it requires considerable

amounts of computing power and milligram quantities of protein. One way in

which 2-D NMR differs from X-ray diffraction is that it uses protein samples in

aqueous solution rather than crystals. This environment is closer to that of

proteins in cells, and thus it is one of the main advantages of the method. The

NMR method most widely used in the deter-mination of protein structure

ultimately depends on the distances between hydrogen atoms, giving results

independent of those obtained by X-ray crystal-lography. The NMR method is

undergoing constant improvement and is being applied to larger proteins as

these improvements progress.

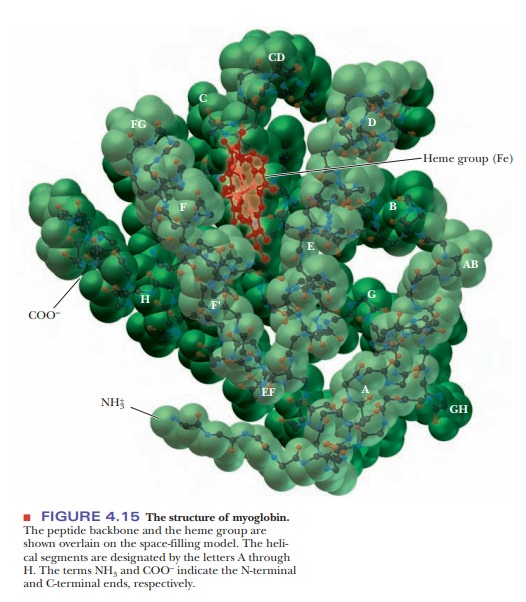

Myoglobin: An Example of Protein Structure

In many

ways, myoglobin is the classic example of a globular protein. We shall use it

here as a case study in tertiary structure. (We shall see the tertiary

structures of many other proteins in context when we discuss their roles in

biochemistry.) Myoglobin was the first protein for which the complete tertiary

structure (Figure 4.15) was determined by X-ray crystallography. The complete

myoglobin molecule consists of a single polypeptide chain of 153 amino acid

residues and includes a prosthetic group, the heme group, which also occurs in hemoglobin. The myoglobin molecule

(including the heme group) has a compact structure, with the interior atoms

very close to each other. This structure provides examples of many of the

forces responsible for the three-dimensional shapes of proteins.

Myoglobin has eight α-helical regions and no β-pleated sheet regions. Approximately 75% of the residues in myoglobin are found in these helical regions, which are designated by the letters A through H. Hydrogen bonding in the polypeptide backbone stabilizes the α-helical regions; amino acid side chains are also involved in hydrogen bonds. The polar residues are on the exterior of the molecule.

The interior of the protein contains almost exclu-sively

nonpolar amino acid residues. Two polar histidine residues are found in the

interior; they are involved in interactions with the heme group and bound

oxygen, and thus play an important role in the function of the molecule. The

planar heme group fits into a hydrophobic pocket in the protein portion of the

molecule and is held in position by hydrophobic attractions between heme’s

porphyrin ring and the nonpolar side chains of the protein. The presence of the

heme group drastically affects the conformation of the polypeptide: The apoprotein

(the polypeptide chain alone, without the prosthetic heme group) is not as

tightly folded as the complete molecule.

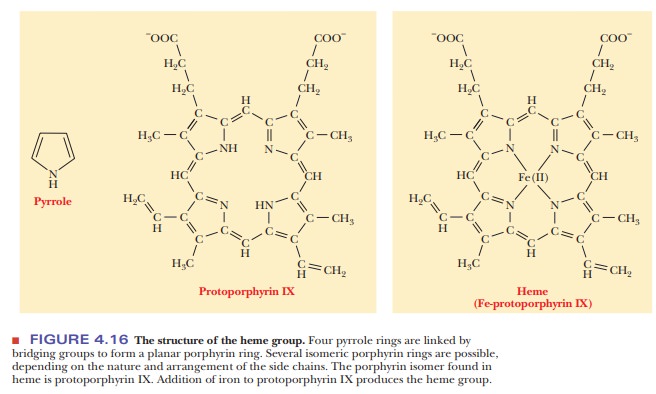

The heme

group consists of a metal ion, Fe(II), and an organic part, pro-toporphyrin IX

(Figure 4.16). (The notation Fe(II) is preferred to Fe2+ when

metal ions occur in complexes.) The porphyrin part consists of four

five-membered rings based on the pyrrole structure; these four rings are linked

by bridging methine (-CH==) groups to form a square planar structure. The

Fe(II) ion has six coordination sites, and it forms six metal–ion complexation

bonds. Four of the six sites are occupied by the nitrogen atoms of the four

pyr-role-type rings of the porphyrin to give the complete heme group. The

pres-ence of the heme group is required for myoglobin to bind oxygen.

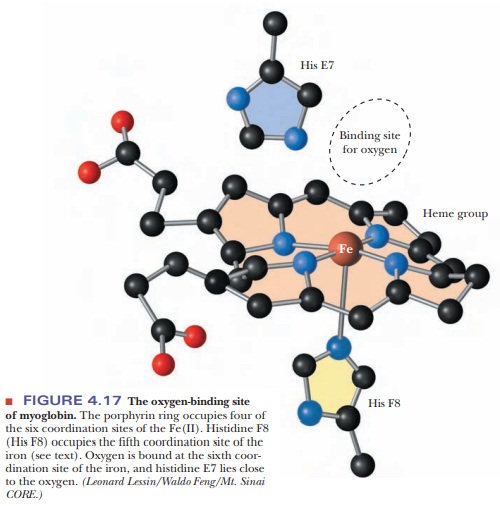

The

fifth coordination site of the Fe(II) ion is occupied by one of the nitrogen

atoms of the imidazole side chain of histidine residue F8 (the eighth residue

in helical segment F). This histidine residue is one of the two in the interior

of the molecule. The oxygen is bound at the sixth coordination site of the

iron. The fifth and sixth coordination sites lie perpendicular to, and on

opposite sides of, the plane of the porphyrin ring. The other histidine residue

in the interior of the molecule, residue E7 (the seventh residue in helical

seg-ment E), lies on the same side of the heme group as the bound oxygen

(Figure 4.17). This second histidine is not bound to the iron, or to any part

of the heme group, but it acts as a gate that opens and closes as oxygen enters

the hydro-phobic pocket to bind to the heme. The E7 histidine sterically

inhibits oxygen from binding perpendicularly to the heme plane, with

biologically important ramifications.

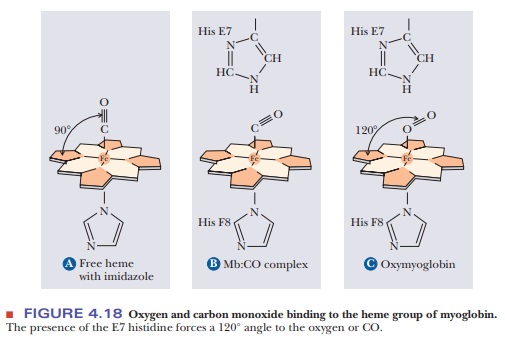

Why does oxygen have imperfect binding to the heme group?

At

first, it would seem counterintuitive that oxygen would bind imperfectly to the

heme group. After all, the job of both myoglobin and hemoglobin is to bind to

oxygen. Wouldn’t it make sense that oxygen should bind strongly? The answer

lies in the fact that more than one molecule can bind to heme. Besides oxygen,

carbon monoxide also binds to heme. The affinity of free heme for carbon

monoxide (CO) is 25,000 times greater than its affinity for oxygen. When carbon

monoxide is forced to bind at an angle in myoglobin because of the steric block

by His E7, its advantage over oxygen drops by two orders of magnitude (Figure

4.18). This guards against the possibility that traces of CO produced during

metabolism would occupy all the oxygen-binding sites on the hemes.

Nevertheless, CO is a potent poison in larger quantities because of its effect

both on oxygen binding to hemoglobin and on the final step of the electron

transport chain. It is also important to remember that although our metabolism

requires that hemoglobin and myoglobin bind oxygen, it would be equally

disastrous if the heme never let the oxygen go. Thus having binding be too

perfect would defeat the purpose of having the oxygen-carrying proteins.

In the

absence of the protein, the iron of the heme group can be oxidized to Fe(III);

the oxidized heme will not bind oxygen. Thus, the combination of both heme and

protein is needed to bind O2 for oxygen storage.

Denaturation and Refolding

The noncovalent interactions that maintain the three-dimensional structure of a protein are weak, and it is not surprising that they can be disrupted easily.

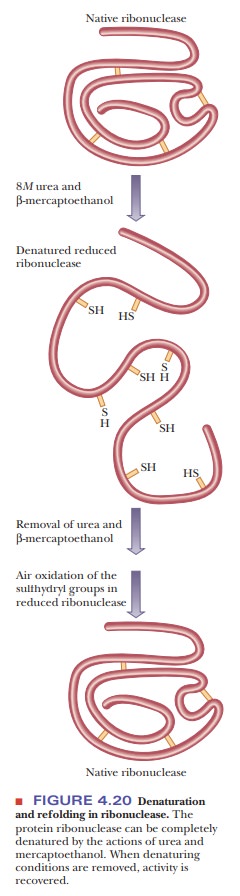

The

unfolding of a protein (i.e., disruption of the tertiary structure) is called denaturation. Reduction of disulfide

bonds leads to even moreextensive unraveling of the tertiary structure.

Denaturation and reduction of disulfide bonds are frequently combined when

complete disruption of the tertiary structure of proteins is desired. Under

proper experimental conditions, the disrupted structure can then be completely

recovered. This process of denaturation and refolding is a dramatic

demonstration of the relationship between the primary structure of the protein

and the forces that determine the tertiary structure. For many proteins,

various other factors are needed for complete refolding, but the important

point is that the primary structure determines the tertiary structure.

Proteins

can be denatured in several ways. One is heat.

An increase in tem-perature favors vibrations within the molecule, and the

energy of these vibra-tions can become great enough to disrupt the tertiary

structure. At either high or low extremes

of pH, at least some of the charges on the protein are missing, and so the

electrostatic interactions that would normally stabilize the native, active

form of the protein are drastically reduced. This leads to denaturation.

The

binding of detergents, such as sodium

dodecyl sulfate (SDS), also dena-tures proteins. Detergents tend to disrupt

hydrophobic interactions. If a deter-gent is charged, it can also disrupt

electrostatic interactions within the protein. Other reagents, such as urea and guanidine hydrochloride, form hydrogen bonds with the protein that

are stronger than those within the protein itself. These two reagents can also

disrupt hydrophobic interactions in much the same way as detergents (Figure

4.19).

b-Mercaptoethanol (HS-CH2-CH2-OH) is

frequently used to reduce disul-fide bridges to two sulfhydryl groups. Urea is

usually added to the reaction mixture to facilitate unfolding of the protein

and to increase the accessibility of the disulfides to the reducing agent. If

experimental conditions are properly chosen, the native conformation of the

protein can be recovered when both mercaptoethanol and urea are removed (Figure

4.20). Experiments of this type provide some of the strongest evidence that the

amino acid sequence of the protein contains all the information required to

produce the complete three-dimensional structure. Protein researchers are

pursuing with some interest the conditions under which a protein can be

denatured-including reduction of disulfides-and its native conformation later recovered.

Summary

Tertiary structure is the complete

three-dimensional arrangement of all the atoms in a protein.

The tertiary structure of proteins is

maintained by different types of cova-lent and noncovalent interactions.

Hydrogen bonding occurs between atoms on the

peptide backbone as well as atoms in the side chains.

Electrostatic attractions between positively

charged side chains and nega-tively charged side chains are also important.

The tertiary structure of proteins is

determined by the techniques of X-ray diffraction and nuclear magnetic

resonance.

Myoglobin, the first protein to have its

tertiary structure determined, is a globular protein for oxygen storage.

Myoglobin is a single polypeptide chain with 153

amino acids, 8 α-helical regions, and a prosthetic group called heme.

The heme has a coordinated iron ion at the

center that binds to oxygen.

Proteins can be denatured by heat, pH, and

chemicals. Denaturation causes the protein to lose its native tertiary

structure.

Some

types of denaturation can be reversed, while others are permanent.

Related Topics