Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Hepatic Disorders

Management of Patients With Hepatitis B Virus (HBV)

HEPATITIS

B VIRUS (HBV)

Unlike

hepatitis A, which is transmitted primarily by the fecal–oral route, hepatitis

B is transmitted primarily through blood (percuta-neous and permucosal routes).

HBV has been found in blood, saliva, semen, and vaginal secretions and can be

transmitted through mucous membranes and breaks in the skin. HBV is also

trans-ferred from carrier mothers to their babies, especially in areas with a

high incidence (ie, Southeast Asia). The infection is usually not via the umbilical

vein, but from the mother at the time of birth and during close contact

afterward.

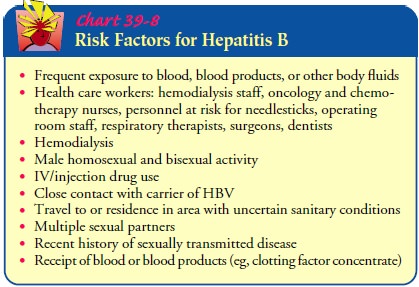

HBV

has a long incubation period. It replicates in the liver and remains in the

serum for relatively long periods, allowing transmission of the virus. Those at

risk for developing hepatitis B include surgeons, clinical laboratory workers,

dentists, nurses, and respiratory therapists. Staff and patients in

hemodialysis and oncology units and sexually active homosexual and bisexual men

and injection drug users are also at increased risk. Screening of blood donors

has greatly reduced the occurrence of hepatitis B after blood transfusion.

Most

people (>90%) who contract hepatitis B infections will develop antibodies

and recover spontaneously in 6 months. The mortality rate from hepatitis B has

been reported to be as high as 10%. Another 10% of patients who have hepatitis

B progress to a carrier state or develop chronic hepatitis with persistent HBV

infection and hepatocellular injury and inflammation. It remains a major cause

of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma world-wide (Chart 39-8).

Clinical Manifestations

Clinically,

the disease closely resembles hepatitis A, but the incu-bation period is much

longer (1 to 6 months). Signs and symp-toms of hepatitis B may be insidious and

variable. Fever and respiratory symptoms are rare; some patients have

arthralgias and rashes. The patient may have loss of appetite, dyspepsia,

abdom-inal pain, generalized aching, malaise, and weakness. Jaundice may or may

not be evident. If jaundice occurs, light-colored stools and dark urine

accompany it. The liver may be tender and enlarged to 12 to 14 cm vertically.

The spleen is enlarged and pal-pable in a few patients; the posterior cervical

lymph nodes may also be enlarged. Subclinical episodes also occur frequently.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

HBV is

a DNA virus composed of the following antigenic particles:

•

HBcAg—hepatitis B core antigen (antigenic material

in an inner core)

•

HBsAg—hepatitis B surface antigen (antigenic

material on surface of HBV)

•

HBeAg—an independent protein circulating in the

blood

•

HBxAg—gene product of X gene of HBV/DNA

Each

antigen elicits its specific antibody and is a marker for different stages of

the disease process:

•

anti-HBc—antibody to core antigen or HBV; persists

dur-ing the acute phase of illness; may indicate continuing HBV in the liver

•

anti-HBs—antibody to surface determinants on HBV;

de-tected during late convalescence; usually indicates recovery and development

of immunity

•

anti-HBe—antibody to hepatitis B e-antigen; usually

signi-fies reduced infectivity

•

anti-HBxAg—antibody to the hepatitis B x-antigen;

may indicate ongoing replication of HBV

HBsAg

appears in the circulation in 80% to 90% of infected pa-tients 1 to 10 weeks

after exposure to HBV and 2 to 8 weeks before the onset of symptoms or an

increase in transferase (transaminase) levels. Patients with HBsAg that

persists for 6 or more months after acute infection are considered HBsAg

carriers (Befeler & Di Bisceglie, 2000). HBeAg is the next antigen of HBV

to appear in the serum. It usually appears within a week of the appearance of

HBsAg and before changes in aminotransferase levels, disappearing from the

serum within 2 weeks. HBV DNA, detected by poly-merase chain reaction testing,

appears in the serum at about the same time as HBeAg. HBcAg is not always

detected in the serum in HBV infection.

About

15% of American adults are positive for anti-HBs, which indicates that they

have had hepatitis B. Anti-HBs may be positive in as many as two thirds of

IV/injection drug users.

Prevention

The

goals of prevention are to interrupt the chain of transmis-sion, to protect

people at high risk with active immunization through the use of hepatitis B

vaccine, and to use passive immu-nization for unprotected people exposed to

HBV.

PREVENTING TRANSMISSION

Continued

screening of blood donors for the presence of hepati-tis B antigens will

further decrease the risk of transmission by blood transfusion. The use of

disposable syringes, needles, and lancets and the introduction of needleless IV

administration sys-tems reduce the risk of spreading this infection from one

patient to another or to health care personnel during the collection of blood

samples or the administration of parenteral therapy. Good personal hygiene is

fundamental to infection control. In the clin-ical laboratory, work areas

should be disinfected daily. Gloves are worn when handling all blood and body

fluids as well as HBAg-positive specimens, or when there is potential exposure

to blood (blood drawing) or to patients’ secretions. Eating and smoking are

prohibited in the laboratory and in other areas exposed to se-cretions, blood,

or blood products. Patient education regarding the nature of the disease, its

infectiousness, and prognosis is a crit-ical factor in preventing transmission

and protecting contacts.

ACTIVE IMMUNIZATION: HEPATITIS B VACCINE

Active

immunization is recommended for individuals at high risk for hepatitis B (eg,

health care personnel and hemodialysis patients). In addition, individuals with

hepatitis C and other chronic liver diseases should receive the vaccine (CDC,

1999).

A

yeast-recombinant hepatitis B vaccine (Recombivax HB) is used to provide active

immunity. Long-term studies of healthy adults and children indicate that

immunologic memory remains intact for at least 5 to 10 years, although antibody

levels may be-come low or undetectable. Measurable levels of antibodies may not

be essential for protection. In those with normal immune sys-tems, booster

doses are not generally required. The CDC (2002) does not recommend booster

doses at this time except for he-modialysis patients. The need for booster

doses may be revisited if reports of hepatitis B increase or an increased

prevalence of the carrier state develops, indicating that protection is

declining.

A

hepatitis B vaccine prepared from plasma of humans chroni-cally infected with

HBV is used only rarely and in patients who are immunodeficient or allergic to

recombinant yeast-derived vaccines.

Both

forms of the hepatitis B vaccine are administered in-tramuscularly in three

doses, the second and third doses 1 and 6 months after the first dose. The

third dose is very important in producing prolonged immunity. Hepatitis B

vaccination should be administered to adults in the deltoid muscle. Antibody

response may be measured by anti-HBs levels 1 to 3 months after complet-ing the

basic course of vaccine, but this testing is not routine and not currently

recommended. Individuals who fail to respond may benefit from one to three

additional doses (Koff, 2001).

People

at high risk, including nurses and other health care per-sonnel exposed to

blood or blood products, should receive active immunization. Health care

workers who have had frequent con-tact with blood are screened for anti-HBs to

determine whether im-munity is already present from previous exposure. The

vaccine produces active immunity to HBV in 90% of healthy people (Koff, 2001).

It does not provide protection to those already exposed to HBV and provides no

protection against other types of viral hep-atitis. Side effects of

immunization are infrequent; soreness and redness at the injection site are the

most common complaints.

Because

hepatitis B infection is frequently transmitted sexually, hepatitis B

vaccination is recommended for all unvaccinated per-sons being evaluated for a

sexually transmitted disease (STD). It is also recommended for those with a

history of an STD, per-sons with multiple sex partners, those who have sex with

injection drug users, and sexually active men who have sex with other men (CDC,

2002).

Universal

childhood vaccination for hepatitis B prevention has been instituted in the

United States. Vaccination was initially targeted for select high-risk

populations, but the U.S. Public

Health

Service and the CDC (1999) have endorsed universal vac-cination of all infants.

Catch-up vaccination is also recommended for all children and adolescents up to

the age of 19 who were not previously immunized. Studies (Chang, 2000; Wu et

al., 1999) show that universal vaccination of all newborns in endemic areas has

dramatically reduced the carrier rate among children and the incidence of

childhood hepatocellular carcinoma. In the United States, studies regarding the

effectiveness of the vaccine are ongo-ing, but it is known that clinical

infection is rarely observed during long-term follow-up of known responders

(ie, health care workers) who seroconverted within 3 months of the third dose

of vaccine (Bircher et al., 1999). Development of chronic carrier states has

not been reported in adult responders to the vaccine.

PASSIVE IMMUNITY: HEPATITIS B IMMUNE GLOBULIN

Hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) provides passive immunity to

hepatitis B and is indicated for people exposed to HBV who have never had

hepatitis B and have never received hepatitis B vaccine. Specific indications

for postexposure vaccine with HBIG include: (1) inadvertent exposure to HBAg-positive blood

through percu-taneous (needlestick) or transmucosal (splashes in contact with

mu-cous membrane) routes, (2) sexual contact with people positive for HBAg, and

(3) perinatal exposure (babies born to HBV-infected mothers should receive HBIG

within 12 hours of delivery). HBIG, which provides passive immunity, is

prepared from plasma selected for high titers of anti-HBs. Prompt immunization

with HBIG (within hours to a few days after exposure to hepatitis B) increases

the likelihood of protection. Both active and passive immunization are

recommended for people exposed to hepatitis B through sexual contact or through

percutaneous or transmucosal routes. If HBIG and hepatitis B vaccine are

administered at the same time, separate sites and separate syringes should be

used. Prophylaxis with high doses of HBIG started at the time of liver

transplantation and con-tinued indefinitely improves survival by thwarting

recurrence of hepatitis B (Bacon & Di Bisceglie, 2000). There has been no

evi-dence that HIV infection can be transmitted by HBIG.

Gerontologic Considerations

The

elderly patient who contracts hepatitis B has a serious risk of severe liver

cell necrosis or fulminant hepatic failure, particularly if other illnesses are

present. The patient is seriously ill and the prog-nosis is poor, so efforts

should be undertaken to eliminate other factors (eg, medications, alcohol) that

may affect liver function.

Medical Management

The

goals of treatment are to minimize infectivity, normalize liver inflammation,

and decrease symptoms. Of all the agents that have been used to treat chronic

type B viral hepatitis, alpha in-terferon as the single modality of therapy

offers the most promise. This regimen of 5 million units daily or 10 million

units three times weekly for 4 to 6 months results in remission of disease in

approximately one third of patients (Befeler & Di Bisceglie, 2000). The

long-term benefits of this treatment are being as-sessed. Interferon must be

administered by injection and has sig-nificant side effects, including fever,

chills, anorexia, nausea, myalgias, and fatigue. Late side effects are more

serious and may necessitate dosage reduction or discontinuation. These include

bone marrow suppression, thyroid dysfunction, alopecia, and bacterial

infections.

Two

antiviral agents (lamivudine [Epvir] and adefovir [Hep-sera]) oral nucleoside

analogs, have been approved for use in chronic hepatitis B in the United

States. Viral resistance may be an issue with these agents, and studies of

their effectiveness alone and in combination with other therapies are ongoing

(Befeler & Di Bisceglie, 2000).

Bed

rest may be recommended, regardless of other treatment, until the symptoms of

hepatitis have subsided. Activities are re-stricted until the hepatic

enlargement and elevated levels of serum bilirubin and liver enzymes have

disappeared. Gradually increased activity is then allowed.

Adequate

nutrition should be maintained; proteins are re-stricted when the liver’s

ability to metabolize protein byproducts is impaired, as demonstrated by

symptoms. Measures to control the dyspeptic symptoms and general malaise

include the use of antacids and antiemetics, but all medications should be

avoided if vomiting occurs. If vomiting persists, the patient may require

hospitalization and fluid therapy. Because of the mode of transmission, the

patient is evaluated for other bloodborne diseases (eg, HIV infection).

Nursing Management

Convalescence

may be prolonged, with complete symptomatic recovery sometimes requiring 3 to 4

months or longer. During this stage, gradual resumption of physical activity is

encouraged after the jaundice has resolved.

The

nurse identifies psychosocial issues and concerns, partic-ularly the effects of

separation from family and friends if the pa-tient is hospitalized during the

acute and infective stages. Even if not hospitalized, the patient will be

unable to work and must avoid sexual contact. Planning is required to minimize

alterations in sensory perception. Planning that includes the family helps to

decrease their fears and anxieties about the spread of the disease.

PROMOTING HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED CARE

Teaching Patients Self-Care.

Because of

the prolonged period ofconvalescence, the patient and family must be prepared

for home care. Provision for adequate rest and nutrition must be ensured. The

nurse informs family members and friends who have had in-timate contact with

the patient about the risks of contracting he-patitis B and makes arrangements

for them to receive hepatitis B vaccine or hepatitis B immune globulin as

prescribed. Those at risk must be aware of the early signs of hepatitis B and

of ways to reduce risk to themselves by avoiding all modes of transmission.

Patients with all forms of hepatitis should avoid drinking alcohol.

Continuing Care.

Follow-up

visits by a home care nurse may beneeded to assess the patient’s progress and

answer family mem-bers’ questions about disease transmission. A home visit also

per-mits assessment of the patient’s physical and psychological status and the

patient and family’s understanding of the importance of adequate rest and

nutrition. The nurse also reinforces previous instructions. Because of the risk

of transmission through sexual intercourse, strategies to prevent exchange of

body fluids are ad-vised, such as abstinence or the use of condoms. The nurse

em-phasizes the importance of keeping follow-up appointments and participating

in other health promotion activities and recom-mended health screenings.

Related Topics