Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Hepatic Disorders

Esophageal Varices - Hepatic Dysfunction

ESOPHAGEAL

VARICES

Bleeding

or hemorrhage from esophageal varices occurs in approx-imately one third of

patients with cirrhosis and varices. The mor-tality rate resulting from the

first bleeding episode is 45% to 50%; it is one of the major causes of death in

patients with cirrhosis (Pomier-Layrargues, Villeneuve, Deschenes et al.,

2001). The mor-tality rate increases with each subsequent bleeding episode.

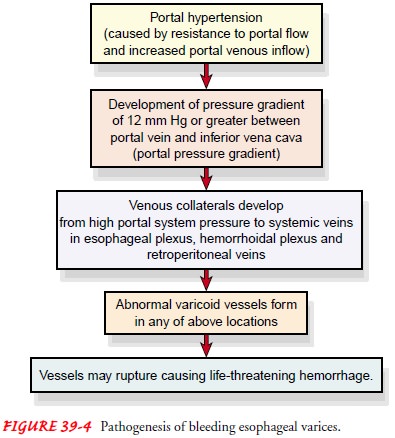

Pathophysiology

Esophageal

varices are dilated, tortuous veins usually found in the submucosa of the lower

esophagus, but they may develop higher in the esophagus or extend into the

stomach. This condition nearly always is caused by portal hypertension, which

in turn is due to ob-struction of the portal venous circulation within the

damaged liver.

Because

of increased obstruction of the portal vein, venous blood from the intestinal

tract and spleen seeks an outlet through collateral circulation (new pathways

of return to the right atrium). The effect is increased pressure, particularly

in the vessels in the submucosal layer of the lower esophagus and upper part of

the stomach. These collateral vessels are not very elastic but rather are

tortuous and fragile and bleed easily (Fig. 39-6). Less common causes of

varices are abnormalities of the circulation in the splenic vein or superior

vena cava and hepatic venothrombosis.

Bleeding

esophageal varices are life-threatening and can result in hemorrhagic shock,

producing decreased cerebral, hepatic, and renal perfusion. In turn, there is

an increased nitrogen load from bleeding into the GI tract and an increased

serum ammonia level, increasing the risk for encephalopathy. Usually the

dilated veins cause no symptoms unless the portal pressure increases sharply

and the mucosa or supporting structures become thin. Then massive hemorrhage

takes place.

Factors

that contribute to hemorrhage are muscular exertion from lifting heavy objects;

straining at stool; sneezing, coughing, or vomiting; esophagitis; irritation of vessels

by poorly chewed foods or irritating fluids; or reflux of stomach contents

(especially alcohol). Salicylates and any medication that erodes the esophageal

mucosa or interferes with cell replication also may contribute to bleeding.

Clinical Manifestations

The patient with bleeding esophageal varices may present with hematemesis, melena, or general deterioration in mental or phys-ical status and often has a history of alcohol abuse. Signs and symptoms of shock (cool clammy skin, hypotension, tachycardia) may be present.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Endoscopy

is used to identify the bleeding site, along with barium swallow,

ultrasonography, CT, and angiography.

ENDOSCOPY

Immediate

endoscopy is indicated to identify the cause and the site of bleeding; at least

30% of patients suspected of bleeding from esophageal varices bleed from other

sources (gastritis, ulcers). Nursing support can be effective in relieving

anxiety during this often-stressful experience. Careful monitoring can detect

early signs of cardiac dysrhythmias, perforation, and hemorrhage.

After

the examination, fluids are not given until the gag reflex returns. Lozenges

and gargles may be used to relieve throat dis-comfort if the patient’s physical

condition and mental status per-mit. If the patient is actively bleeding, oral

intake will not be permitted and the patient will be prepared for further

diagnostic and therapeutic procedures.

PORTAL HYPERTENSION MEASUREMENTS

Portal

hypertension may be suspected if dilated abdominal veins and hemorrhoids are

detected. A palpable enlarged spleen (splenomegaly) and ascites may also be

present. Portal venous pressure can be measured directly or indirectly.

Indirect mea-surement of the hepatic vein pressure gradient is the most com-mon

procedure; it requires insertion of a fluid-filled balloon catheter into the

antecubital or femoral vein. The catheter is ad-vanced under fluoroscopy to a

hepatic vein. A “wedged” pressure (similar to pulmonary artery wedge pressure)

is obtained by oc-cluding the blood flow in the blood vessel; pressure in the

unoc-cluded vessel is also measured. Although the values obtained may

underestimate portal pressure, this measurement may be ob-tained several times

to evaluate the results of therapy.

Direct

measurement of portal vein pressure can be obtained by several methods. During

laparotomy, a needle may be intro-duced into the spleen; a manometer reading of

more than 20 mL saline is abnormal. Another direct measurement requires

inser-tion of a catheter into the portal vein or one of its branches.

En-doscopic measurement of pressure within varices is used only in conjunction

with endoscopic sclerotherapy.

LABORATORY TESTS

Laboratory

tests may include various liver function tests, such as serum aminotransferase,

bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and serum proteins. Splenoportography, which

involves serial or segmental x-rays, is used to detect extensive collateral

circulation in esoph-ageal vessels, which would indicate varices. Other tests

are hepato-portography and celiac angiography. These are usually performed in

the operating room or radiology department.

Medical Management

Bleeding

from esophageal varices can quickly lead to hemor-rhagic shock and is an

emergency. This patient is critically ill, requiring aggressive medical care

and expert nursing care, and is usually transferred to the intensive care unit

for close moni-toring and management.

The

extent of bleeding is evaluated and vital signs are monitored continuously when

hematemesis and melena are present. Signs of potential hypovolemia are noted,

such as cold clammy skin, tachy-cardia, a drop in blood pressure, decreased

urine output, restless-ness, and weak peripheral pulses. Blood volume is

monitored by a central venous pressure or arterial catheter. Oxygen is administered

to prevent hypoxia and to maintain adequate blood oxygenation.

Because

patients with bleeding esophageal varices have intra-vascular volume depletion

and are subject to electrolyte imbal-ance, intravenous fluids with electrolytes

and volume expanders are provided to restore fluid volume and replace

electrolytes. Trans-fusion of blood components also may be required. An

indwelling urinary catheter is usually inserted to permit frequent monitoring

of urine output.

A

variety of pharmacologic, endoscopic, and surgical approaches are used to treat

bleeding esophageal varices, but none is ideal and most are associated with

considerable risk to the patient. Non-surgical treatment of bleeding esophageal

varices is preferable be-cause of the high mortality rate of emergency surgery

for control of bleeding esophageal varices and because of the poor physical

condition of the patient with severe liver dysfunction.

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

In an actively bleeding patient, medications

are administered ini-tially because they can be obtained and administered

quickly; other therapies take longer to initiate. Vasopressin (Pitressin) may

be the initial mode of therapy because it produces constriction of the

splanchnic arterial bed and a resulting decrease in portal pressure. It may be

administered intravenously or by intra-arterial infusion (Menon & Kamath,

2000). Either method requires close moni-toring by the nurse. Vital signs and

the presence or absence of blood in the gastric aspirate indicate the

effectiveness of vasopressin. Monitoring of fluid intake and output and

electrolyte levels is nec-essary because hyponatremia may occur and vasopressin

may have an antidiuretic effect. Coronary artery disease is a contraindication

to the use of vasopressin, because coronary vasoconstriction is a side effect

that may precipitate myocardial infarction.

The

combination of vasopressin and nitroglycerin (adminis-tered by the intravenous,

sublingual, or transdermal route) has been effective in reducing or preventing

the side effects (constriction of coronary vessels and angina) caused by

vasopressin alone.

Somatostatin

and octreotide (Sandostatin) have been reported to be more effective than

vasopressin in decreasing bleeding from esophageal varices without the

vasoconstrictive effects of vaso-pressin. These medications cause selective

splanchnic vasoconstric-tion. Propranolol (Inderal) and nadolol (Corgard),

beta-blocking agents that decrease portal pressure, have been shown to prevent

bleeding from esophageal varices in some patients; however, it is recommended

that they be used only in combination with other treatment modalities such as

sclerotherapy, variceal banding, or balloon tamponade. Nitrates such as

isosorbide (Isordil) lower por-tal pressure by venodilation and decreased cardiac

output. Further studies of these and other medications are necessary to

evaluate their use in the treatment and prevention of bleeding episodes.

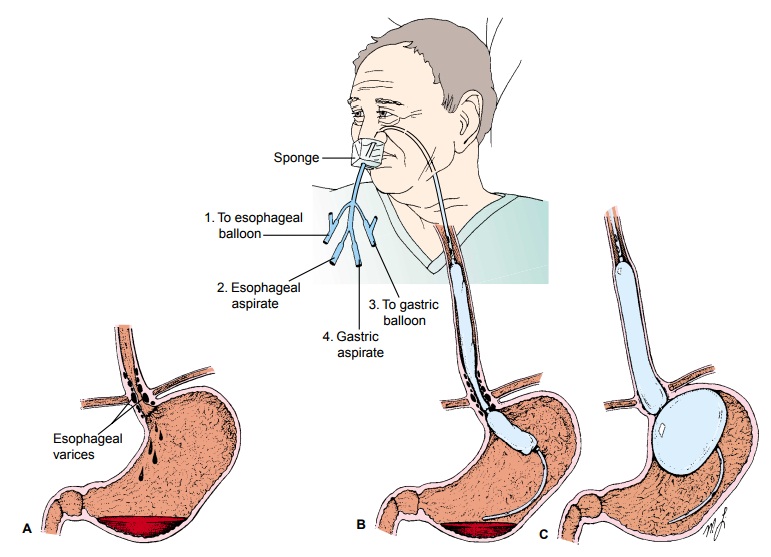

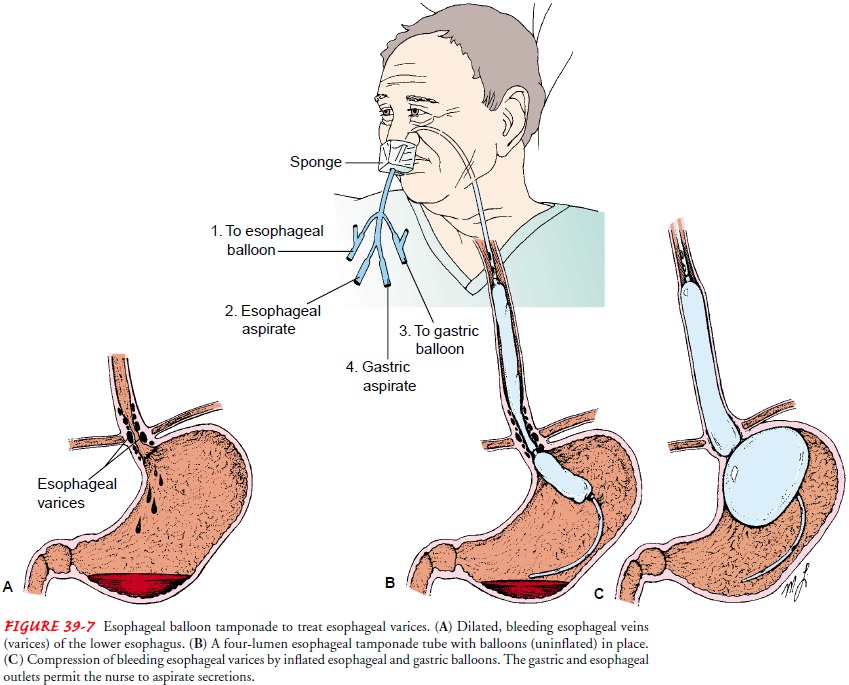

BALLOON TAMPONADE

To

control hemorrhage in certain patients, balloon

tamponade may be used. In this procedure, pressure is exerted on the cardia

(upper orifice of the stomach) and against the bleeding varices by a

double-balloon tamponade (Sengstaken-Blakemore tube) (Fig. 39-7). The tube has

four openings, each with a specific pur-pose: gastric aspiration, esophageal

aspiration, inflation of the gastric balloon, and inflation of the esophageal

balloon.

The balloon in the stomach is inflated with 100 to 200 mL of air. An x-ray confirms proper positioning of the gastric balloon. Then the tube is pulled gently to exert a force against the gastric cardia.

Traction may be applied with weights or by attachment to a football helmet.

Irrigation of the tubing is performed to de-tect bleeding; if returns are

clear, the esophageal balloon is not in-flated. If bleeding continues, the

esophageal balloon is inflated. The desired pressure in the esophageal and

gastric balloons is 25 to 40 mm Hg, as measured by the manometer. There is a

possi-bility of injury or rupture of the esophagus with inflation of the

esophageal balloon, so constant nursing surveillance is necessary.

Gastric

suction is provided by connecting the gastric catheter outlet to suction. The

tubing is irrigated hourly, and drainage will indicate whether bleeding has

been controlled. Room-temperature lavage or irrigation may be used in the

gastric balloon. The pressure within the esophageal balloon is measured and

recorded every 2 to 4 hours via the manometer to detect underinflation or

over-inflation with potential for esophageal injury. When it appears that

bleeding has stopped, the balloons are carefully and sequentially deflated. The

esophageal balloon is deflated first and the patient is monitored for recurrent

bleeding. After several hours without bleeding, the gastric balloon may be

deflated safely. If there is still no bleeding, the tamponade tube is removed.

The therapy is used for as short a time as possible to control bleeding while

emergency treatment is completed and definitive therapies are instituted (no

longer than 24 hours).

Although

balloon tamponade has been fairly successful, there are some inherent dangers.

Displacement of the tube and the in-flated balloon into the oropharynx can

cause life-threatening ob-struction of the airway and asphyxiation. This may

occur if a patient pulls on the tube because of confusion or discomfort. It may

also result from rupture of the gastric balloon, allowing the esophageal

balloon to move into the oropharynx. Sudden rupture of the balloon causes

airway obstruction and aspiration of gastric contents into the lungs. The tube

is tested before insertion to minimize this risk. Aspiration of blood and

secretions into the lungs is frequently associated with balloon tamponade,

especially in the stuporous or comatose patient. Endotracheal intubation before

insertion of the tube protects the airway and minimizes the risk of aspiration.

Ulceration and necrosis of the nose, the mu-cosa of the stomach, or the

esophagus may occur if the tube is left in place or inflated too long or at too

high a pressure.

These

potential complications necessitate intensive and expert care. A confused or

restless patient with this tube in place and bal-loons inflated requires close

monitoring to prevent its displacement. Nursing measures include frequent mouth

and nasal care. For se-cretions that accumulate in the mouth, tissues should be

within easy reach of the patient. Oral suction may be necessary to re-move oral

secretions. Because of the many potential complications, balloon tamponade

tubes are used only as a temporary measure.

The

patient with esophageal hemorrhage is usually extremely anxious and frightened.

Knowing that the nurse is nearby and will respond immediately can help

alleviate some of this anxiety. Tube insertion is uncomfortable and never

pleasant. Explana-tions during the procedure and while the tube is in place may

be reassuring to the patient.

Although

the use of balloon tamponade stops the bleeding in 90% of patients, bleeding

recurs in 60% to 70%, necessitating other treatment modalities (eg,

sclerotherapy or banding) (Menon Kamath, 2000). Once the balloons are deflated

or the tube is re-moved, the patient must be assessed frequently because of the

high risk for recurrent bleeding.

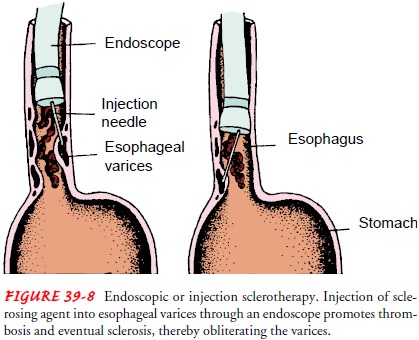

ENDOSCOPIC SCLEROTHERAPY

In

endoscopic sclerotherapy (Fig. 39-8)

(also referred to as injec-tion sclerotherapy), a sclerosing agent is injected

through a fiberop-tic endoscope into the bleeding esophageal varices to promote

thrombosis and eventual sclerosis. The procedure has been used suc-cessfully to

treat acute GI hemorrhage (Menon & Kamath, 2000; O’Grady et al., 2000).

Endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy has been used in the primary prophylaxis of

variceal bleeding, but the results are poorer than those of pharmacotherapy

(Sarin, Lamba, Kumar et al., 1999).

After

treatment, the patient must be observed for bleeding, per-foration of the

esophagus, aspiration pneumonia, and esophageal stricture. Antacids may be

administered after the procedure to counteract the effects of peptic reflux.

ESOPHAGEAL BANDING THERAPY (VARICEAL BAND LIGATION)

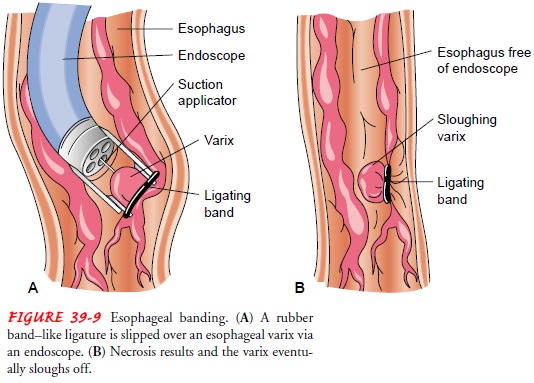

In variceal banding (Fig. 39-9), a

modified endoscope loaded with an elastic rubber band is passed through an

overtube directly onto the varix (or varices) to be banded. After suctioning

the bleeding varix into the tip of the endoscope, the rubber band is slipped

over the tissue, causing necrosis, ulceration, and eventual sloughing of the

varix.

Variceal

banding is comparable to endoscopic sclerotherapy in the effective control of

bleeding. Compared with sclerotherapy, variceal banding also significantly

reduces rebleeding rates, mortal-ity, procedure-related complications, and the

number of sessions needed to eradicate varices. Complications include

superficial ul-ceration and dysphagia, transient chest discomfort, and rarely

esophageal strictures (Menon & Kamath, 2000). Recently, en-doscopic

variceal band ligation has been shown to be safe and more effective than

propanolol for preventing a first bleeding episode (Sarin et al., 1999).

TRANSJUGULAR INTRAHEPATIC PORTOSYSTEMIC SHUNTING

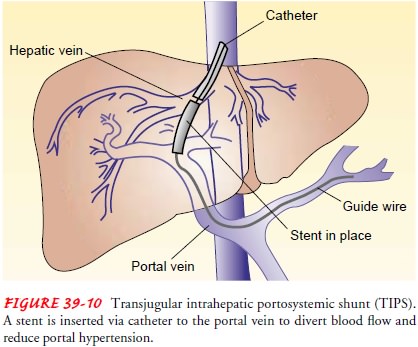

Transjugular

intrahepatic portosystemic shunting (TIPS) is a method of treating esophageal

varices in which a cannula is threaded into the portal vein by the transjugular

route. An expandable stent is inserted and serves as an intrahepatic shunt

between the portal circulation and the hepatic vein (Fig. 39-10), reducing

portal hypertension.

Creation

of a TIPS is indicated for the treatment of recurrent variceal bleeding

refractory to pharmacologic or endoscopic ther-apy. It has also been indicated

for the control of refractory ascites. This technique is also used as a bridge

to liver transplantation. Complications may include bleeding, sepsis, heart

failure, organ perforation, shunt thrombosis, and progressive liver failure

(Pomier-Layrargues et al., 2001).

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

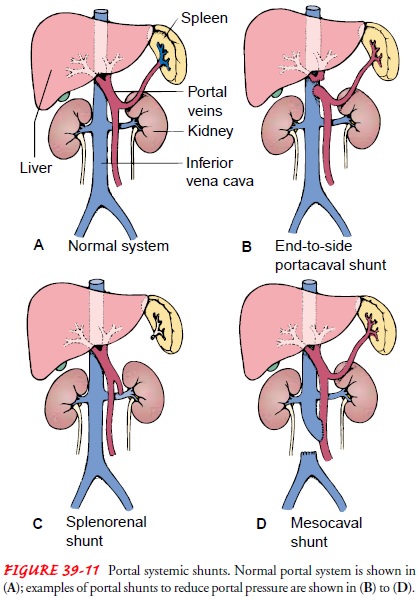

Several surgical procedures have been

developed to treat esophageal varices and to minimize rebleeding, but they are

often accompa-nied by significant risk. Procedures that may be used for

esophageal varices are direct surgical ligation of varices; splenorenal,

meso-caval, and portacaval venous shunts to relieve portal pressure; and

esophageal transection with devascularization. Use of these pro-cedures is

controversial, and studies regarding their effectiveness and outcomes are

ongoing (Bacon & Di Bisceglie, 2000).

Surgical Bypass Procedures.

Surgical

decompression of the por-tal circulation can prevent variceal bleeding if the

shunt remains patent (Bacon & Di Bisceglie, 2000). One of the various

surgical shunting procedures (Fig. 39-11) is the distal splenorenal shunt made

between the splenic vein and the left renal vein after splenectomy. A mesocaval

shunt is created by anastomosing the superior mesenteric vein to the proximal

end of the vena cava or to the side of the vena cava using grafting material.

The goal of distal splenorenal and mesocaval shunts is to drain only a portion

of venous blood from the portal bed to decrease portal pressure; thus, they are

considered selective shunts. The liver continues to receive some portal flow,

and the incidence of encephalopathy may be reduced. Portacaval shunts divert

all portal flow to the vena cava via end-to-side or side-to-side approaches, so

they are considered nonselective shunts.

These procedures are extensive and are not always successful be-cause of secondary thrombosis in the veins used for the shunt as well as complications (eg, encephalopathy, accelerated liver failure). The efficacy of these procedures has been studied extensively. The most recent studies have found that all shunts are equally effective in preventing recurrent variceal bleeding but may cause further im-pairment of liver function and encephalopathy. Partial portacaval shunts with interposition grafts are as effective as other shunts but are associated with a lower rate of encephalopathy (de Franchis, 2000; Krige & Beckingham, 2001; Orozco & Mercado, 2000).

The severity of the disease (by Child’s classification) and the potential

for future liver transplantation guide the physician’s choice of intervention.

If the cause of portal hypertension is the rare Budd-Chiari syndrome or other venous obstructive disease,

aportacaval or a mesoatrial shunt may be performed (see Fig. 39-11). The

mesoatrial shunt is required when the infrahepatic vena cava is thrombosed and

must be bypassed.

Devascularization and Transection.

Devascularization and staple-gun transection procedures to separate the bleeding site from the high-pressure portal system have been used in the emergency management of variceal bleeding. The lower end of the esopha-gus is reached through a small gastrostomy incision; a staple gun permits anastomosis of the transected ends of the esophagus. Re-bleeding is a risk, and the outcomes of these procedures vary among patient populations.

Nursing Management

Overall

nursing assessment includes monitoring the patient’s phys-ical condition and

evaluating emotional responses and cognitive sta-tus. The nurse monitors and

records vital signs and assesses the patient’s nutritional and neurologic

status. This assessment will as-sist in identifying hepatic encephalopathy

resulting from the break-down of blood in the GI tract and a rising serum

ammonia level. Manifestations range from drowsiness to encephalopathy and coma.

Complete rest of the esophagus may be indicated with bleed-ing, so parenteral nutrition is initiated. Gastric suction usually is initiated

to keep the stomach as empty as possible and to prevent straining and vomiting.

The patient often complains of severe thirst, which may be relieved by frequent

oral hygiene and moist sponges to the lips. The nurse closely monitors the

blood pres-sure. Vitamin K therapy and multiple blood transfusions often are

indicated because of blood loss. A quiet environment and calm reassurance may

help to relieve the patient’s anxiety and reduce agitation.

Bleeding

anywhere in the body is anxiety-provoking, resulting in a crisis for the

patient and family. If the patient has been a heavy user of alcohol, delirium

secondary to alcohol withdrawal can complicate the situation. The nurse

provides support and ex-planations regarding medical and nursing interventions.

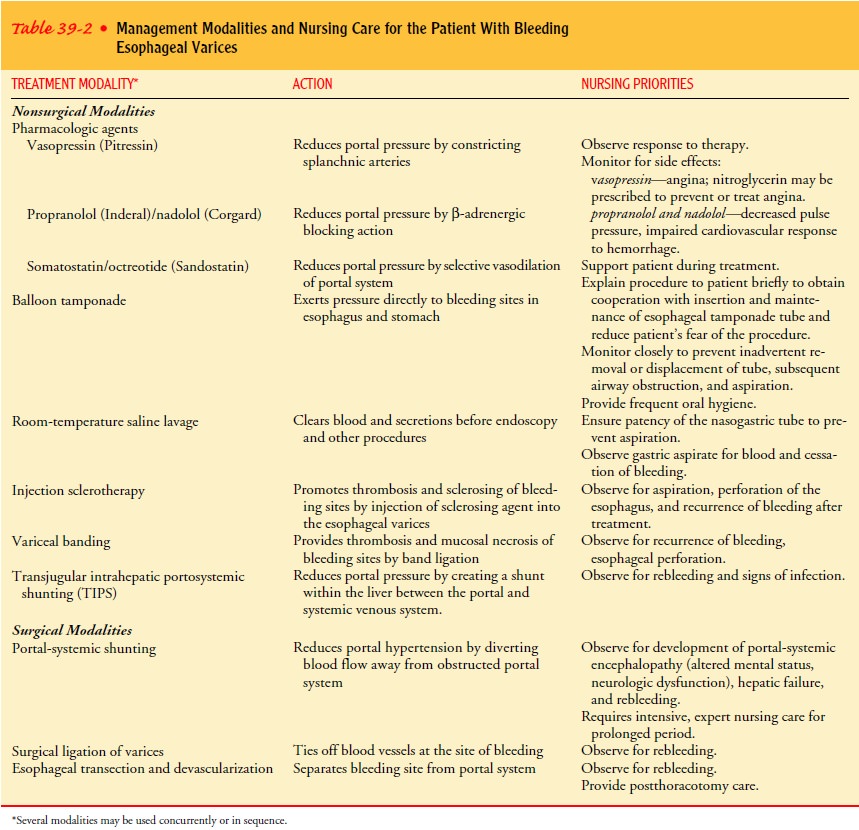

Moni-toring the patient closely will help in detecting and managing complications.Management

modalities and nursing care of the patient with bleeding esophageal varices are

summarized in Table 39-2.

Related Topics