Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Hepatic Disorders

Liver Transplantation

Liver Transplantation

Liver

transplantation is used to treat life-threatening, end-stage liver disease for

which no other form of treatment is available. The transplantation procedure

involves total removal of the dis-eased liver and its replacement with a healthy

liver in the same anatomic location (orthotopic

liver transplantation [OLT]). Removal of the liver leaves a space for the

new liver and permits anatomic reconstruction of the hepatic vasculature and

biliary tract as close to normal as possible.

The

success of liver transplantation depends on successful immunosuppression.

Immunosuppressants currently in use in-clude cyclosporine (Neoral),

corticosteroids, azathioprine (Imuran), mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept), OKT3

(a monoclonal anti-body), tacrolimus (FK506, Prograf), sirolimus (formerly

known as rapamycin [Rapamune]), and antithymocyte globulin. Studies are

underway to find the most effective combination of immuno-suppressive agents

and to identify new agents with fewer side effects (Hebert et al., 1999;

Watson, Friend & Jamieson, 1999).

Despite

the success of immunosuppression in reducing the incidence of rejection of

transplanted organs, liver transplan-tation is not a routine procedure and may

be accompanied by complications related to the lengthy surgical procedure,

immunosuppressive therapy, infection, and the technical diffi-culties

encountered in reconstructing the blood vessels and bil-iary tract.

Long-standing systemic problems resulting from the primary liver disease may

complicate the preoperative and postoperative course. Previous surgery of the

abdomen, in-cluding procedures to treat complications of advanced liver disease

(ie, shunt procedures used to treat portal hypertension and esophageal varices)

increase the complexity of the trans-plantation procedure.

The

indications for liver transplantation are not as limited today as they were

when the procedure was first introduced, due to advances in immunosuppressive

therapy, improvements in bil-iary tract reconstruction, and in some cases the

use of venovenous bypass. General indications for liver transplantation include

irre-versible advanced chronic liver disease, fulminant hepatic failure,

metabolic liver diseases, and some hepatic malignancies. Exam-ples of disorders

that are indications for liver transplantation in-clude hepatocellular liver

disease (eg, viral hepatitis, drug- and alcohol-induced liver disease, and

Wilson’s disease) and cholesta-tic diseases (primary biliary cirrhosis,

sclerosing cholangitis, and biliary atresia).

The

patient being considered for liver transplantation fre-quently has many

systemic problems that influence preopera-tive and postoperative care. Because

transplantation is more difficult when the patient has developed severe GI

bleeding and hepatic coma, efforts are made to perform the procedure before

this stage.

Liver

transplantation is now recognized as an established ther-apeutic modality

rather than an experimental procedure to treat these disorders. As a result,

the number of centers where liver transplantation is performed is increasing.

Patients requiring transplantation are often referred from distant hospitals to

these sites. To prepare the patient and family for liver transplantation,

nurses in all settings must understand the processes and proce-dures of liver

transplantation.

SURGICAL PROCEDURE

The

donor liver is freed from other structures, the bile is flushed from the

gallbladder to prevent damage to the walls of the bil-iary tract, and the liver

is perfused with a preservative andcooled. Before the donor liver is placed in

the recipient, it is flushed with cold lactated Ringer’s solution to remove

potas-sium and air bubbles.

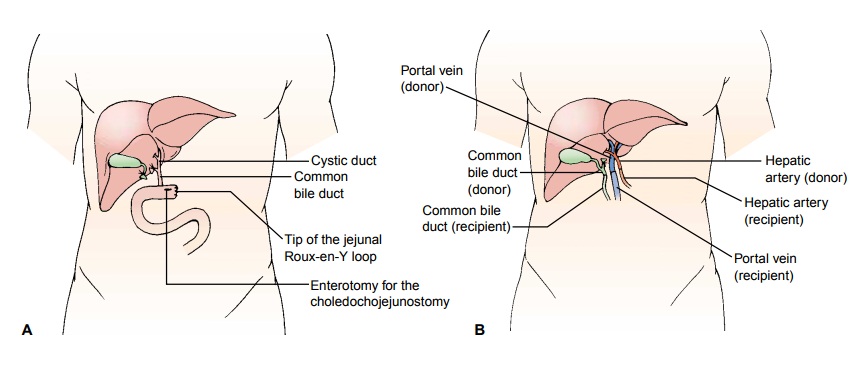

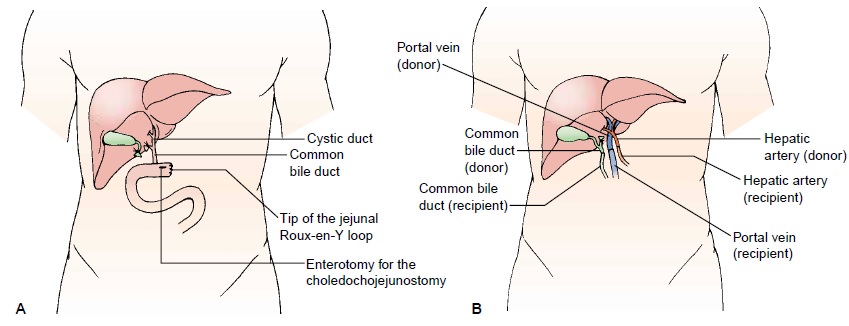

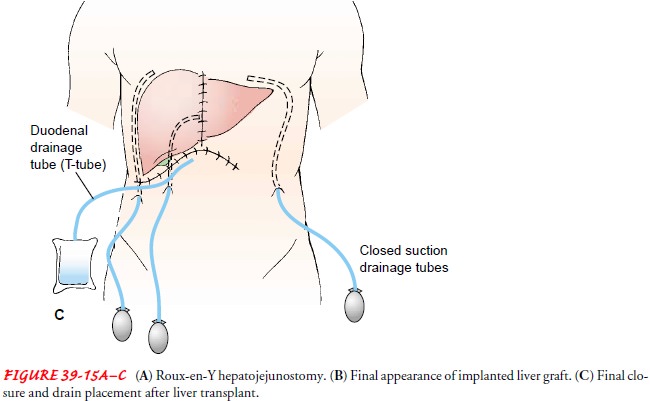

Anastomoses

(connections) of the blood vessels and bile duct are performed between the

donor liver and the recipient liver. Bil-iary reconstruction is performed with

an end-to-end anastomosis of the donor and recipient common bile ducts; a

stented T-tube is inserted for external drainage of bile. If an end-to-end

anastomosis is not possible because of diseased or absent bile ducts, an

end-to-side anastomosis is made between the common bile duct of the graft and a

loop (Roux-en-Y portion) of jejunum (Fig. 39-15A); in this case, bile drainage will be internal and a T-tube will

not be in-serted (Maddrey et al., 2001). Figure 39-15B and C illustrates the

final appearance of the grafted liver and final closure and drain placement.

Liver transplantation is a long surgical procedure, partly be-cause the patient with liver failure often has portal hypertension and

subsequently many venous collateral vessels that must be ligated. Blood loss

during the surgical procedure may be exten-sive. If the patient has adhesions

from previous abdominal surgery, lysis of adhesions is often necessary. If a shunt

proce-dure was performed previously, it must be surgically reversed to permit

adequate portal venous blood supply to the new liver. During the lengthy

surgery, providing regular updates to the family about the progress of the

operation and the patient’s sta-tus is helpful.

COMPLICATIONS

The

postoperative complication rate is high, primarily because of technical

complications or infection. Immediate postoperative complications may include

bleeding, infection, and rejection. Disruption, infection, or obstruction of

the biliary anastomosis and impaired biliary drainage may occur. Vascular

thrombosis and stenosis are other potential complications.

Bleeding

Bleeding

is common in the postoperative period and may result from coagulopathy, portal

hypertension, and fibrinolysis caused by ischemic injury to the donor liver.

Hypotension may occur in this phase secondary to blood loss. Administration of

platelets, fresh-frozen plasma, and other blood products may be necessary.

Hypertension is more common, but its cause is uncertain. Blood pressure

elevation that is significant or sustained is treated.

Infection

Infection

is the leading cause of death after liver transplantation. Pulmonary and fungal

infections are common; susceptibility to in-fection is increased by the

immunosuppression needed to prevent rejection (Maddrey et al., 2001).

Therefore, precautions must be taken to prevent nosocomial infections by strict

asepsis when ma-nipulating arterial lines and urine, bile, and other drainage

sys-tems; obtaining specimens; and changing dressings. Meticulous hand hygiene

is crucial.

Rejection

Rejection

is a key concern. A transplanted liver is perceived by the immune system as a

foreign antigen. This triggers an im-mune response, leading to the activation

of T lymphocytes that attack and destroy the transplanted liver.

Immunosuppressive agents are used long term to prevent this response and

rejection of the transplanted liver. These agents inhibit the activation of

immunocompetent T lymphocytes to prevent the production of effector T cells.

Although

the 1- and 5-year survival rates have increased dra-matically with the use of

new immunosuppressive therapies, these advances are not without major side

effects. A major side effect of cyclosporine, which is widely used in

transplantation, is nephrotoxicity; this problem seems to be dose-related, and

renal dysfunction can be reversed if the dose of cyclosporine is appropriately

decreased or if its use is not initiated immediately. Cyclosporine-related side

effects have caused many centers to use tacrolimus as first-line therapy

because of its efficacy and lower side effect profile.

Corticosteroids,

azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, rapa-mycin, antithymocyte globulin, and

OKT3 are also elements of the various regimens of immunosuppression and may be

used as the initial therapy to prevent rejection, or later to treat rejection.

Liver biopsy and ultrasound may be required to evaluate sus-pected episodes of

rejection.

Retransplantation

is usually attempted if the transplanted liver fails, but the success rate of

retransplantation does not approach that of initial transplantation.

Nursing Management

The

patient considering transplantation and the family have diffi-cult decisions to

make about treatment, use of financial resources, and relocation to another

area to be closer to the medical center. They also must cope with the patient’s

long-standing health prob-lems and perhaps social and family problems

associated with be-haviors that may be responsible for the patient’s liver

failure. Therefore, the time during which the patient and family are

con-sidering liver transplantation and awaiting the news that a liver is

available is often stressful. The nurse must be aware of these issues and

attuned to the emotional and psychological status of the pa-tient and family.

Referral of the patient and family to a psychiatric liaison nurse,

psychologist, psychiatrist, or spiritual advisor may be helpful to them as they

deal with the stressors associated with end-stage liver disease and liver

transplantation.

PREOPERATIVE NURSING INTERVENTIONS

If

irreversible, severe liver dysfunction has been diagnosed, the pa-tient may be

a candidate for transplantation. An extensive diag-nostic evaluation will be

carried out to determine whether the patient is a candidate. The nurse and

other health care team members provide the patient and family with full

explanations about the procedure, the chances of success, and the risks,

in-cluding the side effects of long-term immunosuppression. The need for close

follow-up and lifelong compliance with the thera-peutic regimen, including

immunosuppression, is explained to the patient and family.

Once

accepted as a candidate, the patient is placed on a wait-ing list at the

transplant center and patient information is entered into the United Network

for Organ Sharing (UNOS) computer system so that candidates may be matched with

appropriate or-gans as they become available.

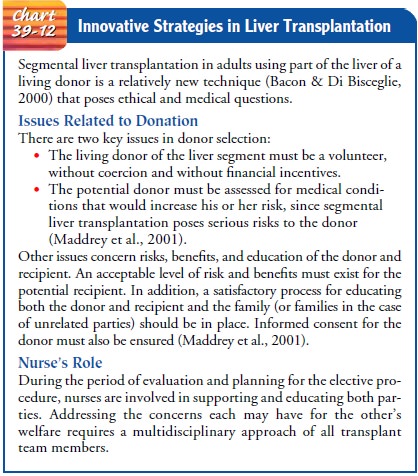

Unless

the patient is having a segmental liver transplanta-tion from a living donor (Chart

39-12), a liver becomes avail-able for transplantation only with the death of

another individual, who is usually healthy except for severe brain injury and

brain death. Thus, the patient and family undergo a stress-ful waiting period,

and the nurse is often the major source of support. The patient must be

accessible at all times in case an appropriate liver becomes available. During

this time, liver function may deteriorate further and the patient may

experi-ence other complications from the primary liver disease. Be-cause of the

current shortage of donor organs, many patients die awaiting transplantation.

Malnutrition,

massive ascites, and fluid and electrolyte distur-bances are treated before

surgery to increase the chance of a suc-cessful outcome. If the patient’s liver

dysfunction has a very rapid onset, as in fulminant hepatic failure, there is

little time or oppor-tunity for the patient to consider and weigh options and

their con-sequences; often this patient is in a coma, and the decision to proceed

with transplantation is made by the family.

The nurse coordinator is an integral member of the transplant team and plays an important role in preparing the patient for liver transplantation. The nurse serves as a patient and family advocate and assumes the important role of link between the patient and the other members of the transplant team. The nurse also serves as a resource to other nurses and health care team members involved in evaluating and caring for the patient.

POSTOPERATIVE NURSING INTERVENTIONS

The

patient is maintained in an environment as free from bac-teria, viruses, and

fungi as possible, because immunosuppressive medications reduce the body’s

natural defenses. In the imme-diate postoperative period, cardiovascular,

pulmonary, renal, neurologic, and metabolic functions are monitored

continu-ously. Mean arterial and pulmonary artery pressures are moni-tored

continuously. Cardiac output, central venous pressure, pulmonary capillary

wedge pressure, arterial and mixed venous blood gases, oxygen saturation,

oxygen demand and delivery, urine output, heart rate, and blood pressure are

used to evalu-ate the patient’s hemodynamic status and intravascular fluid

volume. Liver function tests, electrolyte levels, the coagulation profile,

chest x-ray, electrocardiogram, and fluid output, in-cluding urine, bile, and

drainage from Jackson-Pratt tubes, are monitored closely. Because the liver is

responsible for the stor-age of glycogen and the synthesis of protein and clotting

factors, these substances need to be monitored and replaced in the im-mediate

postoperative period.

Because

of the likelihood of atelectasis and an altered ventilation–perfusion ratio as

a result of the insult to the dia-phragm during the surgical procedure,

prolonged anesthesia, immobility, and postoperative pain, the patient will have

an en-dotracheal tube in place and will require mechanical ventilation during

the initial postoperative period. Suctioning is performed as required and

sterile humidification is provided.

As the

vital signs and condition stabilize, efforts are made to as-sist the patient to

recover from the trauma of this complex surgery. After removal of the

endotracheal tube, the nurse encourages the patient to use an incentive spirometer

to decrease the risk for atelectasis. Once the arterial lines and the urinary

catheter are removed, the patient is assisted to get out of bed, to ambulate as

tolerated, and to participate in self-care to prevent the compli-cations

associated with immobility. Close monitoring for signs and symptoms of liver

dysfunction and rejection will continue throughout the hospital stay. Plans

will be made for close follow-up after discharge as well. Teaching, initiated

during the pre-operative period, continues after surgery.

PROMOTING HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED CARE

Teaching Patients Self-Care.Teaching the

patient and familyabout long-term measures to promote health is crucial for

success of the transplant and represents an important role of the nurse. The

patient and family must understand why they should adhere continuously to the

therapeutic regimen, with special emphasis on the methods of administration,

rationale, and side effects of the prescribed immunosuppressive agents. The

nurse provides written as well as verbal instructions about how and when to

take the medications. To avoid running out of medication or skipping a dose,

the patient must make sure that an adequate supply of medication is available.

Instructions are also provided about the signs and symptoms that indicate

problems that require consul-tation with the transplant team. The patient with

a T-tube in place must be taught how to manage the tube.

Continuing Care.The nurse

emphasizes the importance offollow-up blood tests and visits to the transplant

team. Trough blood levels of immunosuppressive agents are obtained, along with

other blood tests that assess the function of the liver and kidneys. During the

first months, the patient is likely to require blood tests two or three times a

week. As the patient’s condition stabilizes, blood studies and visits to the

transplant team are less frequent. The importance of routine ophthalmologic

examina-tions is emphasized because of the increased incidence of cataracts and

glaucoma with the long-term corticosteroid therapy used with transplantation.

Regular oral hygiene and follow-up dental care, with administration of

prophylactic antibiotics before dental treatments, are recommended because of

the immunosuppression.

The

nurse reminds the patient that although a successful transplantation will not

return him or her to normal, it does in-crease the chances for survival and a

more normal life than before transplantation if rejection and infection can be

prevented. Many patients have lived successful and productive lives after

receiving a liver transplant. In fact, pregnancy can be considered 1 year after

transplantation. Successful outcomes have been reported, but these pregnancies

are considered high risk for mother and in-fant (Sherlock & Dooley, 2002).

Related Topics