Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Hepatic Disorders

Ascites - Hepatic Dysfunction

ASCITES

Pathophysiology

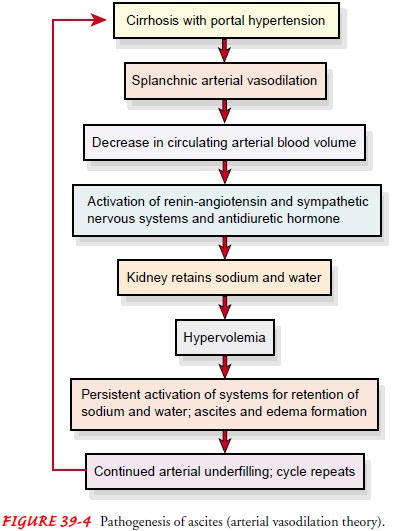

The

mechanisms responsible for the development of ascites are not completely

understood. Portal hypertension and the result-ing increase in capillary

pressure and obstruction of venous blood flow through the damaged liver are

contributing factors. The fail-ure of the liver to metabolize aldosterone

increases sodium and water retention by the kidney. Sodium and water retention,

increased intravascular fluid volume, and decreased synthesis of al-bumin by

the damaged liver all contribute to fluid moving from the vascular system into

the peritoneal space. Loss of fluid into the peritoneal space causes further

sodium and water retention by the kidney in an effort to maintain the vascular

fluid volume, and the process becomes self-perpetuating.

As a

result of liver damage, large amounts of albumin-rich fluid, 15 L or more, may

accumulate in the peritoneal cavity as ascites. With the movement of albumin

from the serum to the peritoneal cavity, the osmotic pressure of the serum

decreases. This, combined with increased portal pressure, results in move-ment

of fluid into the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 39-4).

Clinical Manifestations

Increased

abdominal girth and rapid weight gain are common presenting symptoms of

ascites. The patient may be short of breath and uncomfortable from the enlarged

abdomen, and striae and distended veins may be visible over the abdominal wall.

Fluid and electrolyte imbalances are common.

Assessment and Diagnostic Evaluation

The presence and extent of ascites are assessed by percussion of the abdomen. When fluid has accumulated in the peritoneal cavity, the flanks bulge when the patient assumes a supine position. The presence of fluid can be confirmed either by percussing for shift-ing dullness or by detecting a fluid wave (Fig. 39-5). A fluid wave is likely to be found only when a large amount of fluid is present.

Daily

measurement and recording of abdominal girth and body weight are essential to

assess the progression of ascites and its re-sponse to treatment.

Medical Management

DIETARY MODIFICATION

The

goal of treatment for the patient with ascites is a negative sodium balance to

reduce fluid retention. Table salt, salty foods, salted butter and margarine,

and all ordinary canned and frozen foods (foods that are not specifically

prepared for low-sodium diets) should be avoided. It may take 2 to 3 months for

the patient’s taste buds to adjust to unsalted foods. In the meantime, the

taste of un-salted foods can be improved by using salt substitutes such as

lemon juice, oregano, and thyme. Commercial salt substitutes need to be approved

by the physician because those containing ammonia could precipitate hepatic

coma. Most salt substitutes contain potas-sium and should be avoided if the

patient has impaired renal func-tion. The patient should make liberal use of

powdered, low-sodium milk and milk products. If fluid accumulation is not

controlled with this regimen, the daily sodium allowance may be reduced

fur-ther to 500 mg, and diuretics may be administered.

Dietary

control of ascites via strict sodium restriction is diffi-cult to achieve at

home. The likelihood that the patient will fol-low even a 2-g sodium diet

increases if the patient and the person preparing meals understand the

rationale for the diet and receive periodic guidance about selecting and

preparing appropriate foods. Approximately 10% of patients with ascites respond

to these measures alone. Nonresponders and those who find sodium restriction

difficult require diuretic therapy.

DIURETICS

Use of diuretics along with sodium

restriction is successful in 90% of patients with ascites. Spironolactone

(Aldactone), an aldosterone-blocking agent, is most often the first-line

therapy in patients with ascites from cirrhosis. When used with other diuretics,

spirono-lactone helps prevent potassium loss. Oral diuretics such as furosemide

(Lasix) may be added but should be used cautiously because with long-term use

they may also induce severe sodium depletion (hyponatremia).

Ammonium

chloride and acetazolamide (Diamox) are con-traindicated because of the

possibility of precipitating hepatic coma. Daily weight loss should not exceed

1 to 2 kg (2.2 to 4.4 lb) in patients with ascites and peripheral edema or 0.5

to 0.75 kg (1.1 to 1.65 lb) in patients without edema. Fluid restriction is not

attempted unless the serum sodium concentration is very low.

Possible

complications of diuretic therapy include fluid and electrolyte disturbances

(including hypovolemia, hypokalemia, hyponatremia, and hypochloremic alkalosis)

and encephalopathy. Encephalopathy may be precipitated by dehydration and hypo-volemia.

Also, when potassium stores are depleted, the amount of ammonia in the systemic

circulation increases, which may cause impaired cerebral functioning and

encephalopathy.

BED REST

In

patients with ascites, an upright posture is associated with ac-tivation of the

renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and sympa-thetic nervous system (Porth,

2002). This results in reduced renal glomerular filtration and sodium excretion

and a decreased re-sponse to loop diuretics. Bed rest may be a useful therapy, espe-cially

for patients whose condition is refractory to diuretics.

PARACENTESIS

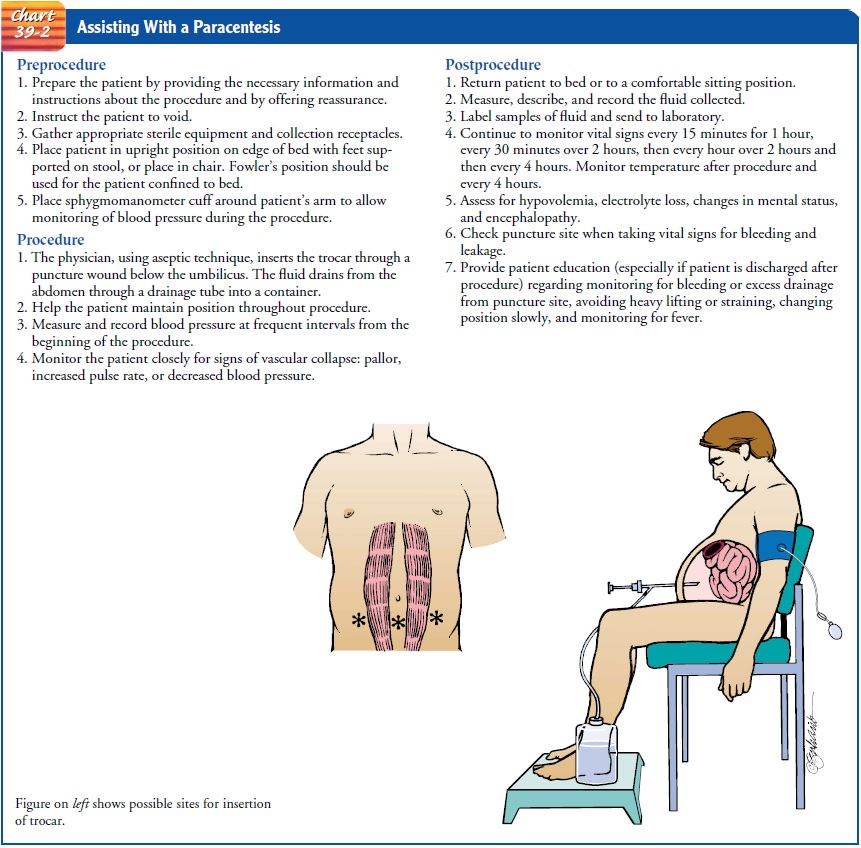

Paracentesis

is the removal of fluid (ascites) from the peritoneal cavity through a small

surgical incision or puncture made through the abdominal wall under sterile

conditions. Ultrasound guid-ance may be indicated in some patients at high risk

for bleeding because of an abnormal coagulation profile or in those who have

had previous abdominal surgery and who may have adhesions. Paracentesis was

once considered a routine form of treatment for ascites but is now performed

primarily for diagnostic examination of ascitic fluid, for treatment of massive

ascites that is resistant to nutritional and diuretic therapy and that is

causing severe problems to the patient, and as a prelude to diagnostic imaging

studies, peritoneal dialysis, or surgery. A sample of the ascitic fluid may be

sent to the laboratory for analysis. Cell count, albumin and total protein

levels, culture, and occasionally other tests are performed.

Use of

large-volume (5 to 6 liters) paracentesis has been shown to be a safe method

for treating patients with severe ascites. This technique, in combination with

the intravenous infusion of salt-poor albumin or other colloid, has become the

standard treatment for refractory, massive ascites (Krige & Beckingham,

2001; Menon Kamath, 2000). The salt-poor albumin helps reduce edema by causing

the ascitic fluid to be drawn back into the bloodstream and ultimately

eliminated by the kidneys. The procedure pro-vides only temporary removal of

fluid; it rapidly recurs, necessi-tating repeated removal. Nursing care of the

patient undergoing paracentesis is presented in Chart 39-2.

OTHER METHODS OF TREATMENT

Insertion of a peritoneovenous shunt to redirect ascitic fluid from the peritoneal cavity into the systemic circulation is a treatment modality for ascites, but this procedure is seldom used because of the high complication rate and high incidence of shunt failure. The shunt is reserved for those who are resistant to diuretic ther-apy, are not candidates for liver transplantation, have abdominal adhesions, or are ineligible for other procedures because of severe medical conditions, such as cardiac disease.

Nursing Management

If a

patient with ascites from liver dysfunction is hospitalized, nursing measures

include assessment and documentation of in-take and output, abdominal girth,

and daily weight to assess fluid status. The nurse monitors serum ammonia and

electrolyte levels to assess electrolyte balance, response to therapy, and

in-dicators of encephalopathy.

PROMOTING HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED CARE

Teaching Patients Self-Care.

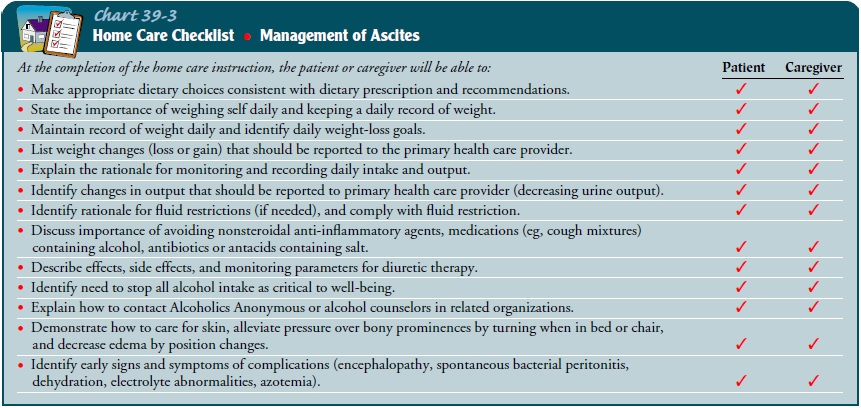

The patient

treated for ascites islikely to be discharged with some ascites still present.

Before hos-pital discharge, the nurse teaches the patient and family about the

treatment plan, including the need to avoid all alcohol intake, ad-here to a

low-sodium diet, take medications as prescribed, and check with the physician before taking any

new medications (Chart 39-3). Additional patient and family teaching addresses

skin care and the need to weigh the patient daily and to watch for and report

signs and symptoms of complications.

Continuing Care.

A referral for home care may be warranted,especially if the patient lives alone or cannot provide self-care. The home visit enables the nurse to assess changes in the patient’s condition and weight, abdominal girth, skin, and cognitive and emotional status. The home care nurse assesses the home envi-ronment and the availability of resources needed to adhere to the treatment plan (eg, a scale to obtain daily weights, facilities to pre-pare and store appropriate foods, resources to purchase needed medications). It is important to assess the patient’s adherence to the treatment plan and the ability to buy, prepare, and eat appropriate foods. The nurse reinforces previous teaching and emphasizes the need for regular follow-up and the importance of keeping scheduled health care appointments.

Related Topics