Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Regional Anesthesia & Pain Management: Chronic Pain Management

Low Back Pain & Related Syndromes

LOW BACK PAIN & RELATED SYNDROMES

Back pain is an extremely common complaint

and a major cause of work disability worldwide. Lum-bosacral strain,

degenerative disc disease, and myo-fascial syndromes are the most common

causes. Low back pain, with or without associated leg pain, may also have

congenital, traumatic, degenerative, inflammatory, infectious, metabolic,

psychologi-cal, and neoplastic causes. Moreover, back pain can be due to

disease processes in the abdomen andpelvis, particularly those affecting

retroperitoneal structures (pancreas, kidneys, ureters, and aorta), the uterus

and adnexa, the prostate, and the recto-sigmoid colon. Disorders of the hip can

also mimic back disorders. A positive Patrick’s sign (or Patrick’s test)—ie,

the elicitation of pain in the hip or sacro-iliac joint when the examiner

places the ipsilateral heel of the supine patient on the contralateral knee and

presses down on the ipsilateral knee—helps identify back pain due to hip or

sacroiliac joint dis-orders. This sign is also referred to by an acronym, FABERE

(sign), because the movement of the leg involves flexion, abduction, external rotation, and extension.

1. Applied Anatomy of the Back

The back can be described in terms of anterior and posterior elements. The anterior elements consist ofcylindrical vertebral

bodies interconnected by inter-vertebral discs and supported by anterior and

poste-rior longitudinal ligaments. The posterior elements are bony arches

extending from each vertebral body, consisting of two pedicles, two transverse

processes, two laminae, and a spinous process. The transverse and spinous

processes provide points of attachment for the muscles that move and protect

the spinal col-umn. Adjacent vertebrae also articulate posteriorly by two

gliding facet joints.

Spinal structures are innervated by the sinu-vertebral branches and

posterior rami of spinal nerves. The sinuvertebral nerve arises before each

spinal nerve divides into anterior and posterior rami, and reenters the

intervertebral foramen to innervate the posterior longitudinal ligament, the

posterior annulus fibrosus, periosteum, dura, and epidural vessels. Paraspinal

structures are supplied by the posterior primary ramus. Each facet joint is

innervated by the medial branch of the posterior primary rami of the spinal

nerves above and below the joint.

As lumbar spinal nerve roots exit the dural

sac, they travel down 1–2 cm laterally before exit-ing through their respective

intervertebral foramina; thus, for example, the L5 nerve root leaves the dural

sac at the level of the L4–L5 disc (where it is more likely to be compressed)

but leaves the spinal canal beneath the L5 pedicle opposite the L5–S1 disc.

2.Paravertebral Muscle & Lumbosacral Joint Sprain/Strain

Approximately 80–90% of low back pain is due

to sprain or strain associated with lifting heavy objects, falls, or sudden

abnormal movements of the spine. The term sprain

is generally used when the pain is related to a well-defined acute injury,

whereas strain is used when the pain

is more chronic and is likely related to repetitive minor injuries.

Injury to paravertebral muscles and ligaments

results in reflex muscle spasm, which may or may not be associated with trigger

points. The pain is usually dull and aching, and occasionally radiates down the

buttocks or hips. Sprain is a self-limited benign pro-cess that resolves in 1–2

weeks. Symptomatic treat-ment consists of rest and oral analgesics.

The sacroiliac joint is particularly vulnerable to rotational injuries.

It is one of the largest joints in the body and functions to transfer weight

from the upper body to the lower extremities. Acute or chronic injury can cause

slippage, or subluxation, of the joint. Pain originating from this joint is

char-acteristically located along the posterior ilium and radiates down the

hips and posterior thigh to the knees. The diagnosis is suggested by tenderness

on palpation, particularly on the medial aspect of the posterior superior iliac

spine, and by compression of the joints. Pain relief following injection of the

joint with local anesthetic (3 mL) is diagnostic and may also be therapeutic.

Injection of intraarticular steroid medication may be considered. For

poten-tially longer duration of analgesia, radiofrequency ablation may be

performed at the dorsal ramus of L5 as well as the lateral branches of the S1,

S2, and S3 nerves if the patient responded well to local anes-thetic injections

of the sacroiliac joint or to diagnos-tic injections of these nerves.

3. Buttock Pain

Buttock pain may be due to several different fac-tors, and can be quite

debilitating. Coccydynia (or, coccygodynia) may the result of trauma to the

coc-cyx or surrounding ligaments. It may resolve by means of physical therapy,

coccygeal nerve blocks to the lateral aspects of the coccyx, or ablative or

neuromodulatory techniques. Piriformis syndromepresents as pain in the buttock,

which can be accom-panied by numbness and tingling in distribution of the

sciatic nerve. The nerve may or may not be entrapped. Injection of local

anesthetic into the belly of this muscle or into trigger points located at the

origin and insertion of the muscle may help relieve the pain.

4. Degenerative Disc Disease

Intervertebral discs bear at least one third of the weight of the spinal

column. Their central portion, the nucleus pulposus, is composed of gelatinous

material early in life. This material degenerates and becomes fibrotic with

advancing age and follow-ing trauma. The nucleus pulposus is ringed by the

annulus fibrosus, which is thinnest posteriorly and bounded superiorly and

inferiorly by cartilaginous plates. Disc (discogenic) pain may be due to one of

two major mechanisms: (1) protrusion or extru-sion of the nucleus pulposus

posteriorly or (2) loss of disc height, resulting in the reactive formation of

bony spurs (osteophytes) from the rims of the ver-tebral bodies above and below

the disc. Degenera-tive disc disease most commonly affects the lumbar spine

because it is subjected to the greatest motion and because the posterior

longitudinal ligament is thinnest at L2–L5. Factors such as increased body

weight and cigarette smoking may play a role in the development of lumbar disc

disease. The role of the disc in producing chronic back pain is not clearly

understood. In patients with persistent axial low back pain, the history and

physical examination may provide clues. If the patient has pain when sitting or

standing, or maintaining a certain position for an extended period of time,

there may be an element of discogenic pain.

Discography is a procedure that is often used

to try to provide some objective evidence of the role of a given disc in

producing a patient’s back pain. After a needle is inserted into the disc, the

opening pressure can be assessed; a subsequent injection of radiocontrast

material produces increased pressure that may reproduce the patient’s pain and

may pro-vide radiographic identification of anatomic abnor-malities within the

disc (eg, a rent or tear). It the pain produced with injection is similar to

that which the patient experiences on a daily basis, it is deemed concordant pain. If

not, it is deemed discordant. Insome

circumstances, the pressure in the disc fol-lowing injection is not

significantly higher than the opening pressure. This may be due to the presence

of a fissure in the disc that tracks to the epidural space. Risks of

discography include infection and discitis, which may be difficult to treat

because the disc is relatively avascular.

Treatment options for discogenic pain include conservative therapy,

steroid injections into the disc, intradiscal biacplasty, involving heating the

poste-rior annulus of the disc by way of radiofrequency ablation, and surgical

fusion with bone graft or hardware placement; each has shown mixed degrees of

success. The evaluation and treatment of disco-genic pain is an area of significant

controversy and ongoing research.

Herniated (Prolapsed) Intervertebral Disc

Weakness and degeneration of the annulus

fibrosus and posterior longitudinal ligament can cause her-niation of the

nucleus pulposus posteriorly into the spinal canal. Ninety percent of disc

hernia-tions occur at L5–S1 or L4–L5. Symptoms usually develop following

flexion injuries or heavy lifting and may be associated with bulging,

protru-sion, or extrusion of the disc. Disc herniations usu-ally occur

posterolaterally and often result in compression of adjacent nerve roots,

producing pain that radiates along that dermatome (radiculopathy). Sciatica describes pain along the

sciatic nerve due tocompression of the lower lumbar nerve roots. When disc

material is extruded through the annulus fibro-sus and posterior longitudinal

ligament, free frag-ments can become wedged in the spinal canal or the

intervertebral foramina. Less commonly a large disc bulges or large fragments

extrude posteriorly, compressing the cauda equina in the dural sac; in these

instances patients can experience bilateral pain, urinary retention, or, less

commonly, fecal incontinence.

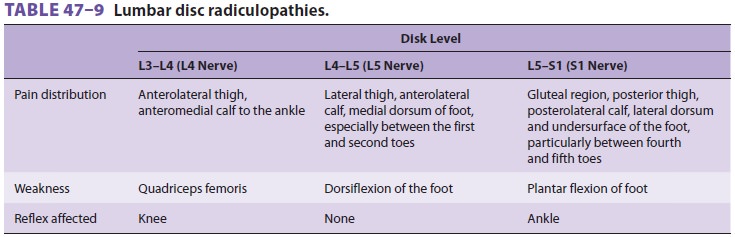

Pain associated with disc disease is

aggravated by bending, lifting, prolonged sitting, or anything that increases

intraabdominal pressure, such as sneezing, coughing, or straining. It is

usually relieved by lying down. Numbness or weakness is indicative

of radiculopathy (Table 47–9). Bulging of the disc through

the posterior longitudinal ligament can also produce low back pain that

radiates to the hips or buttocks. Straight leg-raising tests may be used to

assess nerve root compression. With the patient supine and the knee fully

extended, the leg on the affected side is raised and the angle at which the

pain develops is noted; dorsiflexion of the ankle with the leg raised typically

exacerbates the pain by further stretching the lumbosacral plexus. Pain while

raising the contralateral leg is an even more reliable sign of nerve

compression.

The use of MRI has increased dramatically in

the past decade in association with a two- to three-fold increase in back

surgeries, although this has not correlated with improved patient outcome. The

American Pain Society’s clinical practice guidelines for low back pain do not

recommend routine imag-ing or other diagnostic tests for patients with

nonspe-cific low back pain. Up to 30–40% of asymptomatic persons have

abnormalities of spinal structures on CT or MRI. In addition, the patient’s

awareness of his or her imaging abnormalities may influence self-perception of

health and functional ability.

Imaging studies and further tests should be

acquired when severe or progressive neurological deficits are present, or when

serious underlying con-ditions are suspected. CT myelography is the most

sensitive test for evaluating subtle neural compres-sion. Discography may be

considered when the pain pattern does not match the clinical findings. A

centrally herniated disc will usually cause pain at the lower level, and a

laterally protruded disc will cause pain at the same level as the disc. For

example, a centrally located disc herniation at L4–L5 may compress the L5 nerve

root whereas a laterally located disc herniation at this level may compress the

L4 nerve root.

The natural course of herniated disc

disor-ders is generally benign and the duration of pain is usually less than 2

months. Over 75% of patients treated nonsurgically, even those with

radiculopa-thy, have complete or near-complete pain relief. The goals of

treatment should therefore be to allevi-ate the pain and rehabilitate the

patient to return to a functional quality of life. Acute back pain due to a

herniated disc can be initially managed with modification of activity and with

medications such as NSAIDs and acetaminophen. A short course of opioids may be

considered for patients with severe pain. After the acute symptoms subside, the

patient can be referred to a physical therapist for instruc-tion on exercises

to improve lower back health. Patients who smoke tobacco should be advised to

stop smoking, not only for the obvious health ben-efits but also because

nicotine further compromises blood flow to the relatively avascular

intervertebral disc. Percutaneous disc decompression involving extraction of a

small amount of nucleus pulposus may help to decompress the nerve root. For

patients with acute-onset weakness correlating with the level of the disc

herniation, surgical management should be considered.

When symptoms persist beyond 3 months,

the pain may be considered chronic and may require a multidisciplinary

approach. Physical therapy continues to be a very important component of

rehabilitation. NSAIDs and antidepressants are also helpful, and percutaneous

interventions may be con-sidered. Of note, back supports should be discour-aged

because they may weaken paraspinal muscles.

Spinal Stenosis

Spinal stenosis is a disease of advancing

age. Degen-eration of the nucleus pulposus reduces disc height and leads to

osteophyte formation (spondylosis) at the endplates of adjoining vertebral

bodies. In con-junction with facet joint hypertrophy and with liga-mentum

flavum hypertrophy and calcification, this process leads to progressive

narrowing of the neural foramina and spinal canal. Neural compression may cause

radiculopathy that mimics a herniated disc. Extensive osteophyte formation may

compress multiple nerve roots and cause bilateral pain. The back pain usually

radiates into the buttocks,thighs, and legs. It is characteristically worse

with exercise and relieved by rest, particularly sitting with the spine flexed

(the “shopping cart sign”). The terms pseudoclaudication

and neurogenic claudication areused

to describe such pain that develops with pro-longed standing or ambulation. The

diagnosis is sug-gested by the clinical presentation and is confirmed by MRI,

CT, or myelography. Electromyography and nerve conduction studies may be useful

in evaluat-ing neurological compromise.

Patients with mild to moderate stenosis and

radicular symptoms may obtain benefit from epi-dural steroid injections via a

transforaminal, inter-laminar, or caudal approach. This may help these

individuals tolerate physical therapy. Those with moderate to severe stenosis

may be amenable to more recently developed procedures, such as the minimally

invasive lumbar decompression (MILD) procedure, which involves percutaneously

sculpting the lamina and ligamentum flavum to reduce central canal compression.

Severe multilevel symptoms may warrant surgical decompression.

5. Facet Syndrome

Degenerative changes in the facet

(zygapophyseal) joints may also produce back pain. Pain may be near the

midline; may radiate to the gluteal region, thigh,and knee; and may be

associated with muscle spasm. Hyperextension and lateral rotation of the spine

usually exacerbate the pain. The diagnosis may be confirmed if pain relief is

obtained following intraar-ticular injection of local anesthetic solution into

affected joints or by blockade of the medial branch of the posterior division

(ramus) of the spinal nerves that innervate them. Long-term studies suggest

that medial branch nerve blocks are more effective than facet joint injections.

Medial branch rhizotomy may provide long-term analgesia for patients with facet

joint disease.

6. Cervical Pain

Although most spine-related pain due to disc

dis-ease, spinal stenosis, or degenerative changes in the zygapophyseal joints

is felt in the low back and lower extremities, patients may have cervical pain

attrib-uted to these processes. A key anatomic difference is that the cervical

nerve roots, unlike those in the thoracic and lumbar spine, exit the foramina

above the vertebral bodies for which they are named. This occurs until the

level of C7, where the extra cervi-cal nerve roots, C8, exit below the pedicles

of C7, thus transitioning to the nomenclature of the tho-racic- and

lumbar-level vertebral bodies and nerve root denominations. The clinical

examination may help to identify the nerve root that is affected with

confirmation by a selective nerve root block. Risks inherent with percutaneous

cervical procedures include accidental intravascular injection of local

anesthetic or steroid. Particulate steroid injections in the neck have been

associated with devastating outcomes such as spinal cord injury and death and

should be avoided.

For primarily axial pain in the neck with extension into the head or to

the shoulders, cervi-cal medial branch blocks may clarify the diagnosis.

Long-term analgesia may be obtained with radiofre-quency ablation of the medial

branches innervating the zygapophyseal joints.

7. Congenital Abnormalities

Congenital abnormalities of the back are often asymptomatic and remain

occult for many years. Abnormal spinal mechanics can

make the patient prone to back pain, and in some instances, pro-gressive

deformities. Relatively common anomalies include sacralization of L5 (the

vertebral body is fused to the sacrum), lumbarization of S1 (it func-tions as a

sixth lumbar vertebra), spondylolysis (a disruption of the pars

interarticularis), spondylolis-thesis (displacement anteriorly of one vertebral

body on the next due to disruption of the posterior ele-ments, usually the

pars), and spondyloptosis (sub-luxation of one vertebral body on another

resulting in one body in front of the next). The diagnosis is made

radiographically. Spinal fusion may be nec-essary in patients with progressive

symptoms and spinal instability.

8. Tumors

Benign primary tumors of the spine include hem-angiomas, osteomas,

aneurysmal bone cysts, and eosinophilic granulomas. Malignant spine tumors

include osteosarcomas, Ewing’s sarcoma, and giant cell tumors. In addition,

breast, lung, prostate, renal, gastrointestinal, and thyroid carcinomas,

lympho-mas, and multiple myelomas frequently metasta-size to the lumbar spine.

Pain is usually constant and may be associated with localized tenderness over

involved vertebrae. Bony destruction, with or without neural or vascular

compression, produces the pain. Intradural tumors such as meningiomas,

schwannomas, ependymomas, and gliomas can present with a radiculopathy and may

rapidly prog-ress to flaccid paralysis. The primary site may be asymptomatic or

difficult to localize, thus requiring imaging studies for diagnosis. Treatment

options usually involve surgical decompression, chemo-therapy, radiation

therapy, and palliative symptom relief.

9. Infection

Bacterial infections of the spine usually

begin as dis-citis before progressing to osteomyelitis, and can be due to

pyogenic as well as tuberculous organisms. Patients may present with chronic

back pain with-out fever or leukocytosis (eg, spinal tuberculosis). Those with

acute discitis, osteomyelitis, or epidural abscess present with acute pain,

fever, leukocytosis, elevated sedimentation rate, and elevated C-reactive

protein, warranting immediate initiation of antibiot-ics. Urgent surgical

intervention is indicated when the patient also suffers from acute weakness.

10. Arthritides

Ankylosing spondylitis is a familial disorder

that is associated with histocompatibility antigen HLA-B27. It typically

presents as low back pain associated with early morning stiffness in a young

patient, usu-ally male. The pain has an insidious onset and may initially

improve with activity. After a few months to years, the pain gradually

intensifies and is associated with progressively restricted movement of the

spine. Diagnosis may be difficult early in the disease, but radiographic

evidence of sacroiliitis is usually pres-ent. As the disease progresses, the

spine develops a characteristic “bamboo-like” radiographic appear-ance. Some

patients develop arthritis of the hips and shoulders, as well as extraarticular

inflamma-tory manifestations. Treatment is primarily directed at functional

preservation of posture. NSAIDs, particularly indomethacin, are effective

analge-sics that reduce the early morning stiffness. Anti– tumor necrosis

factor-α agents have been shown

to decrease the progression of ankylosing spondylitis when administered early

in the course of therapy. These agents include infliximab (Remicaid),

etan-ercept (Enbrel), adalimumab (Humira), and golim-umab (Simponi). Although

this treatment approach shows promise, patients may be at an increased risk for

infection and the development of lymphoma.

Patients with Reiter’s syndrome, psoriatic arthritis, or inflammatory

bowel disease may also present with low back pain, but extraspinal

mani-festations are usually more prominent. Rheumatoid arthritis usually spares

the spine except for the zyg-apophyseal joints of the cervical spine.

Related Topics