Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Regional Anesthesia & Pain Management: Chronic Pain Management

Epidural Injections

Epidural

Injections

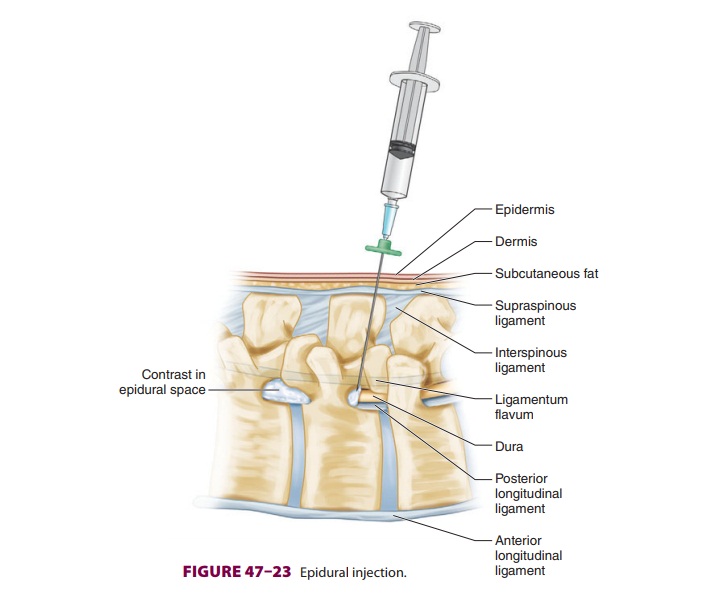

Epidural steroid injections ( Figure

47–23) are used for symptomatic relief of pain

associated with nerve root compression (radiculopathy). Pathological studies

often demonstrate inflammation following disc herniation. Clinical improvement

appears to be correlated with the resolution of nerve root edema. Epidural

steroid injections are clearly superior to local anesthetics alone. They are

most effective when given within 2 weeks of pain onset but appear to be of

little benefit in the absence of neural compres-sion or irritation. Long-term

studies have failed to show any persistent benefit after 3 months, and these

injections may change the time course of pain relief without changing long-term

outcomes.

The two most commonly used agents are meth-ylprednisolone

acetate (40–80 mg) and triamcino-lone diacetate (40–80 mg). Dexamethasone is

being used with increased frequency due to its smaller particulate size

(smaller than an erythrocyte). Intravascular injection of steroid suspension

with larger particulate size may lead to embolic compli-cations. The steroid

may be injected with diluent (saline) or local anesthetic in volumes of 6–10 mL

or 10–20 mL for lumbar and caudal injections, respec-tively. Simultaneous

injection of opioids offers no added benefit and may significantly increase

risks. The epidural needle should be cleared of the ste-roid prior to its

withdrawal to prevent formation of a fistula tract or skin discoloration.

Injection of local anesthetic along with the steroid can be help-ful if the

patient has significant muscle spasm, but it is associated with risks of

intrathecal, subdural, and intravascular injection. The presenting pain is

often transiently intensified following injection, and the local anesthetic

provides immediate pain relief until the steroidal antiinflammatory effects

take place, usually within 12–48 h.

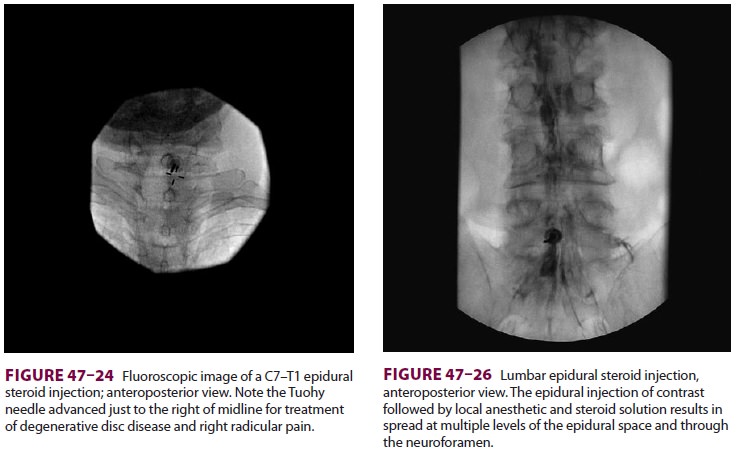

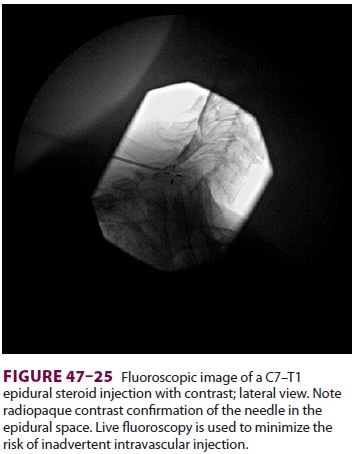

Epidural steroid injections may be most

effec-tive when the injection is at the site of injury. Only a single injection

is given if complete pain relief is achieved. If there is a good but temporary

response, a second injection may be given 2–4 weeks later. Larger or more

frequent doses increase the risk of adrenal suppression and systemic side

effects. Most pain practitioners utilize fluoroscopy for epidural injection and

confirm correct placement with injec-tion of radiopaque contrast ( Figures

47–24 through 47–26). A transforaminal epidural steroid injectionmay be more effective than

the standard interlami-nar epidural technique, especially for radicular pain.

The needle is directed under fluoroscopic guidance into the foramen of the

affected nerve root; contrast is then injected to confirm spread into the

epidural space and absence of intravascular injection prior to steroid

injection. This technique differs from a

selective nerve root block (SNRB) in two

important ways; with an SNRB, the needle does not enter the foramen and the

injected solution tracks along the nerve but not into the epidural space. The

SNRB may be helpful as a diagnostic procedure for the surgeon who is

considering a foraminotomy at a particular affected level based upon imaging,

clinical presenta-tion, and the results of the SNRB.

Caudal injection may be used in patients with

previous back surgery when scarring and anatomic distortion make lumbar

epidural injections more difficult. Unfortunately, migration of the steroid to

the site of injury may not be optimal. The use of a catheter to direct the

injection within the sacral and epidural canal may improve outcome.

However,above the level of S2, there is a risk of thecal perfora-tion with a

stylet-guided catheter. Intrathecal steroid injections are not recommended

because the ethyl-ene glycol preservative in the suspension has been implicated

in arachnoiditis following unintentional subarachnoid injections.

Related Topics