Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Regional Anesthesia & Pain Management: Chronic Pain Management

Evaluation of the Patient with Chronic Pain

Evaluation of the Patient with Chronic Pain

The evaluation of any patient with pain

should include several key components. Informationabout location, onset, and

quality of pain, as well as alleviating and exacerbating factors, should be

obtained, along with a pain history that includes pre-vious therapies and

changes in symptoms over time. In addition to physical symptoms, chronic pain

usu-ally involves a psychological component that should be addressed as well.

Questionnaires, diagrams, and pain scales are useful tools in helping patients

ade-quately describe the characteristics of their pain and how it affects their

quality of life. Information gath-ered during the physical examination can help

dis-tinguish pain location, type, and systemic sequelae, if any. Imaging

studies such as plain radiographs, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI), and bone scans can often suggest physiological causes. All

components are necessary for a comprehensive evaluation of the pain patient prior

to determining appropriate treatment options.

PAIN MEASUREMENT

Reliable quantitation of pain severity helps deter-mine therapeutic

interventions and evaluate the efficacy of treatments. This is a challenge,

however, because pain is a subjective experience that is influ-enced by

psychological, cultural, and other variables. Clear definitions are necessary,

because pain may be described in terms of tissue destruction or bodily or

emotional reaction.

The numerical rating scale, Wong-Baker FACES rating scale, visual analog

scale (VAS), and McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) are most commonly used. In the

numerical scale, 0 corresponds to no pain and 10 is intended to reflect the worst possible pain. The Wong-Baker FACES pain scale, designed for

children 3 years of age and older, is useful in patients with whom

communication may be difficult. The patient is asked to point to various facial

expressions rang-ing from a smiling face (no pain) to an extremely unhappy one

that expresses the worst possible pain. The VAS is a 10-cm horizontal line

labeled “no pain” at one end and “worst pain imaginable” on the other end. The

patient is asked to mark on this line where the intensity of the pain lies. The

distance from “no pain” to the patient’s mark numerically quantifies the pain.

The VAS is a simple and efficient method that correlates well with other

reliable methods.

The MPQ is a checklist of words describ-ing symptoms. Unlike other pain

rating methods that assume pain is one-dimensional and describe intensity but

not quality, the MPQ attempts to define the pain in three major dimensions:

(1) sensory–discriminative

(nociceptive pathways), (2) motivational–affective (reticular and limbic

structures), and (3) cognitive–evaluative (cerebral cortex). It contains 20

sets of descriptive words that are divided into four major groups: 10 sensory,

5 affective, 1 evaluative, and 4 miscellaneous. The patient selects the sets

that apply to his or her pain and circles the words in each set that best

describe the pain. The words in each class are given rank according to severity

of pain. A pain rating index is derived based on the words chosen.

PSYCHOLOGICAL EVALUATION

Psychological evaluation is useful whenever

medical evaluation fails to reveal an apparentcause for pain, when pain

intensity, characteristics, or duration are disproportionate to disease or

injury, or when depression or other psychological issues are apparent. These

types of evaluations help define the role of psychological or behavioral

factors. The most commonly used tests are the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality

Inventory (MMPI) and Beck Depression Inventory.

The MMPI is a 566-item true–false

question-naire that attempts to define the patient’s personality on 10 clinical

scales. Three validity scales serve to identify patients deliberately trying to

hide traits or alter the results. Cultural differences can affect

scores.Moreover, the test is lengthy and some patients find its questions

insulting. The MMPI is used primar-ily to confirm clinical impressions about the

role of psychological factors; it cannot reliably distinguish between “organic”

and “functional” pain.

Depression is very common in patients with chronic pain. It is often

difficult to determine the relative contribution of depression to the suffering

associated with pain. The Beck Depression Inven-tory is a useful test for

identifying patients with major depression.

Several tests have been developed to assess functional limitations or

impairment (disability). These include the Multidimensional Pain Inventory

(MPI), Medical Outcomes Survey 36-Item Short Form (SF-36), Pain Disability

Index (PDI), and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI).

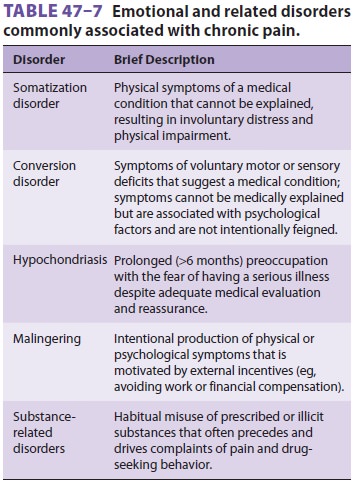

Emotional disorders are commonly associated

with complaints of chronic pain, and chronic pain often results in varying degrees

of psychological dis-tress. Determination of which came first is often

dif-ficult. In either case, both the pain and emotional distress need to be

treated. Table 47–7 lists emo-tional

disorders in which treatment should be pri-marily directed at the emotional

disorder.

ELECTROMYOGRAPHY & NERVE CONDUCTION STUDIES

Electromyography and nerve conduction studies complement one another and

are useful for con-firming the diagnosis of entrapment syndromes, radicular

syndromes, neural trauma, and poly-neuropathies. They can often distinguish

between neurogenic and myogenic disorders. Patterns of abnormalities can

localize a lesion to the spinal cord, nerve root, limb plexus, or peripheral

nerve. In addi-tion, they may also be useful in excluding “organic” disorders

when psychogenic pain or a “functional” syndrome is suspected.

Electromyography employs needle electrodes to record potentials in individual muscles. Mus-cle potentials are recorded first while the muscle is at rest and then as the patient is asked to move the muscle. A triphasic motor unit action poten-tial is normally seen as the patient voluntarily moves the muscle. Abnormal findings suggestive of denervation include persistent insertion poten-tials, the presence of positive sharp waves, fibrillary activity, or fasciculation potentials. Abnormalities in muscles produce changes in amplitude and duration as well as polyphasic action potentials.

Peripheral nerve conduction studies employ supramaximal stimulations of

motor or mixed sen-sorimotor nerve, whereas muscle potentials are recorded over

the appropriate muscle. The time between the onset of the stimulation and the

onset of the muscle potential (latency) is a measurement of the fastest

conducting motor fibers in the nerve. The amplitude of the recorded potential

indicates the number of functional motor units, whereas its duration reflects

the range of conduction velocities in the nerve. Conduction velocity can be

obtained by stimulating the nerve from two points and com-paring the latencies.

When a pure sensory nerve is evaluated, the nerve is stimulated while action

potentials are recorded either proximally or distally (antidromic

conduction).Nerve conduction studies distinguish between mononeuropathies (due

to trauma, compression, or entrapment) and polyneuropathies. The latter include

systemic disorders that may produce abnor-malities that are widespread and

symmetrical or that are random (eg, mononeuropathy multiplex).

Related Topics