Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Diabetes Mellitus

Implementing the Plan - Nursing Management of Patients With Diabetes Mellitus

IMPLEMENTING

THE PLAN

Teaching Experienced Diabetic Patients

The

nurse should continue to assess the skills of patients who have had diabetes

for many years, because it is estimated that up to 50% of patients may make

errors in self-care. Assessment of these patients must include direct

observation of skills, not just their self-report of self-care behaviors. In

addition, these patients must be fully aware of preventive measures related to

foot care, eye care, and risk factor management. If patients are experienc-ing

long-term diabetic complications for the first time, they may go through the

grieving process again. Some of these patients may have a renewed interest in

diabetes self-care in the hope of delay-ing further complications. Other

patients may be overwhelmed by feelings of guilt and depression. The patient is

encouraged to discuss feelings and fears related to complications; the nurse

meanwhile provides appropriate information regarding diabetic complications.

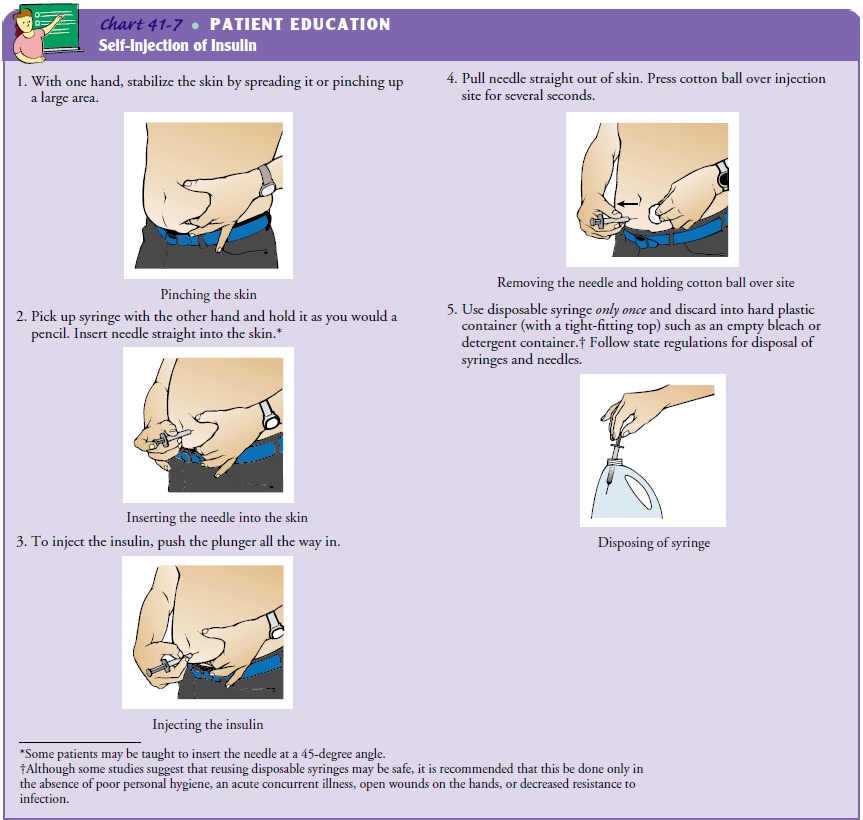

Teaching Patients to Self-Administer Insulin

Insulin

injections are administered into the subcutaneous tissue with the use of

special insulin syringes. A variety of syringes and injection-aid devices are

available. Chart 41-7 provides important information to include and evaluate

when teaching patients about insulin. Basic information includes explanation of

the equipment, insulins, syringes, and mixing insulin.

STORING INSULIN

Cloudy

insulins should be thoroughly mixed by gently inverting the vial or rolling it

between the hands before drawing the solu-tion into a syringe or a pen.

Whether

insulin is the short- or long-acting preparation, the vials not in use should

be refrigerated and extremes of tempera-ture should be avoided; insulin should

not be allowed to freeze and should not be kept in direct sunlight or in a hot

car. The insulin vial in use should be kept at room temperature to reduce local

irritation at the injection site, which may occur when cold insulin is injected.

If a vial of insulin will be used up in 1 month, it may be kept at room

temperature. Patients should be instructed to always have a spare vial of the

type or types of insulin they use (ADA, Insulin Administration, 2003). Spare

vials should be refrigerated.

Insulin

bottles should also be inspected for flocculation, which is a frosted, whitish

coating inside the bottle of intermediate- or long-acting insulins. This occurs

most commonly with human insulins that are not refrigerated. If a frosted,

adherent coating is present, some of the insulin is bound and should not be

used.

SELECTING SYRINGES

Syringes must be matched with the insulin concentration (eg, U-100). Currently, three sizes of U-100 insulin syringes are available:

•

1-mL (cc) syringes that hold 100 units

•

0.5-mL syringes that hold 50 units

•

0.3-mL syringes that hold 30 units

The

concentration of insulin used in the United States is U-100; that is, there are

100 units per milliliter (or cubic cen-timeter). Syringe size varies. Small

syringes allow patients who re-quire small amounts of insulin to measure and

draw up the amount of insulin accurately. Patients who require large amounts of

insulin would use larger syringes. Although there is a U-500 (500 units/mL)

concentration of insulin available by special order for patients who have

severe insulin resistance and require mas-sive doses of insulin, it is rarely

used. (Individuals who travel out-side of the United States should be aware

that insulin is available in 40-U concentration to avoid dosing errors.)

Most

insulin syringes have a disposable 27- to 29-gauge nee-dle that is

approximately 0.5 inch long. The smaller syringes are marked in 1-unit

increments and may be easier to use for patients with visual deficits or patients

taking very small doses of insulin. The 1-mL syringes are marked in 2-unit

increments. A small dis-posable insulin needle (29- to 30-gauge, 8 mm long) is

available for very thin patients and children.

PREPARING THE INJECTION: MIXING INSULINS

When

rapid- or short-acting insulins are to be given simultane-ously with

longer-acting insulins, they are usually mixed together in the same syringe;

the longer-acting insulins must be mixed thoroughly before use. There is some

question as to whether the two insulins are stable if the mixture is kept in

the syringe for more than 5 to 15 minutes. This may depend on the ratio of the

insulins as well as the time between mixing and injecting. When regular insulin

is mixed with long-acting insulin, there is a bind-ing reaction that slows the

action of the regular insulin. This may also occur to a greater degree when

mixing regular insulin with one of the Lente insulins. Patients are advised to

consult their health care provider for advice on this matter. The most impor-tant

issue is that patients be consistent in how they prepare their insulin

injections from day to day.

While

there are varying opinions regarding which type of insulin (short- or

longer-acting) should be drawn up into the syringe first when they are going to

be mixed, the ADA recom-mends that the regular insulin be drawn up first. The

most impor-tant issues are, again, that patients be consistent in technique so

as not to draw up the wrong dose accidentally or the wrong type of insulin, and

that patients not inject one type of insulin into the bottle containing a

different type of insulin (ADA, Insulin Administration, 2003).

For

patients who have difficulty mixing insulins, two options are available: they

may use a premixed insulin, or they may have prefilled syringes prepared.

Premixed insulins are available in sev-eral different ratios of NPH insulin to

regular insulin. The ratio of 70/30 (70% NPH and 30% regular insulin in one

bottle) is the most common and is available as Novolin 70/30 (Novo Nordisk) and

Humulin 70/30 (Lilly). Other ratios available in-clude 80/20, 60/40, and 50/50.

The ratio of 75% NPL and 25% insulin lispro is also available (ADA, Insulin

Administration, 2002). NPL is used only to mix with Humalog; its action is the

same as NPH. The appropriate initial dosage of premixed insulin must be

calculated so that the ratio of NPH to regular insulin most closely

approximates the separate doses needed.

For

patients who can inject insulin but who have difficulty drawing up a single or

mixed dose, syringes can be prefilled with the help of home care nurses or

family and friends. A 3-week supply of insulin syringes may be prepared and

kept in the refriger-ator. The prefilled syringes should be stored with the

needle in an upright position to avoid clogging of the needle (ADA, Insulin

Administration, 2003).

WITHDRAWING INSULIN

Most

(if not all) of the printed materials available on insulin dose preparation

instruct patients to inject air into the bottle of insulin equivalent to the

number of units of insulin to be withdrawn. The rationale for this is to

prevent the formation of a vacuum in-side the bottle, which would make it

difficult to withdraw the proper amount of insulin. Some nurses who specialize

in diabetes report that some patients (who have been taking insulin for many

years) have stopped injecting air before withdrawing the insulin. These

patients found that the extra step was not necessary for ac-curately drawing up

the insulin dose. Most patients find it easier to withdraw the insulin by

eliminating the step and report no dif-ficulty in preparing the proper insulin

dose.

Eliminating

this step (or alternating it by, for instance, inject-ing a syringe full of air

into the vial once per week) facilitates the teaching process for some patients

learning to draw up insulin for the first time. Some patients become confused

with the sequence of steps involved in injecting air into two separate bottles

in two different amounts before drawing up a mixed dose. For many in-dividuals,

including elderly ones, simplifying the procedure for preparing insulin

injections may help them maintain indepen-dence in daily living.

As

with other variations in insulin injection technique, the most important

factors are that the patient maintain consistency in the procedure and that the

nurse be flexible when teaching new patients or assessing the skills of

experienced patients.

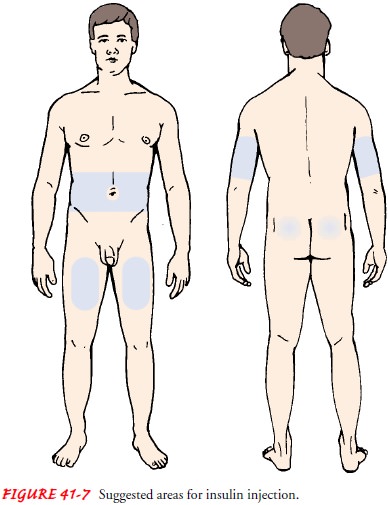

SELECTING AND ROTATING THE INJECTION SITE

The

four main areas for injection are the abdomen, arms (poste-rior surface),

thighs (anterior surface), and hips (Fig. 41-7). In-sulin is absorbed faster in

some areas of the body than others. The speed of absorption is greatest in the

abdomen and decreases pro-gressively in the arm, thigh, and hip.

Systematic

rotation of injection sites within an anatomic area is recommended to prevent

localized changes in fatty tissue (lipodystrophy). In addition, to promote

consistency in insulin absorption, patients should be encouraged to use all

available in-jection sites within one area rather than randomly rotating sites

from area to area (ADA, Insulin Administration, 2002). For ex-ample, some

patients almost exclusively use the abdominal area, administering each

injection 0.5 to 1 inch away from the previ-ous injection. Another approach to

rotation is always to use the same area at the same time of day. For example,

patients may in-ject morning doses into the abdomen and evening doses into the

arms or legs.

A few

general principles apply to all rotation patterns. First, patients should try

not to use the same site more than once in 2 to 3 weeks. In addition, if the

patient is planning to exercise, in-sulin should not be injected into the limb

that will be exercised, because it will be absorbed faster, and this may result

in hypo-glycemia.

In the past, patients were taught to rotate injections from one area to the next (eg, injecting once in the right arm, then once in the right abdomen, then once in the right thigh). Patients who still use this system must be taught to avoid repeated injec-tions into the same site within an area. However, as previously stated, it is preferable for the patient to use the same anatomic area at the same time of day consistently; this reduces day-to-day variation in blood glucose levels because of different absorption rates.

PREPARING THE SKIN

Use of

alcohol to cleanse the skin is not recommended, but pa-tients who have learned

this technique often continue to use it. They should be cautioned to allow the

skin to dry after cleansing with alcohol. If the skin is not allowed to dry

before the injection, the alcohol may be carried into the tissues, resulting in

a localized reddened area.

INSERTING THE NEEDLE

There

are varying approaches to inserting the needle for insulin injections. The

correct technique is based on the need for the in-sulin to be injected into the

subcutaneous tissue. Injection that is too deep (eg, intramuscular) or too

shallow may affect the rate of absorption of the insulin. Aspiration (inserting

the needle and then pulling back on the plunger to assess for blood being drawn

into the syringe) is generally not recommended with self-injection of insulin.

Many patients who have been using insulin for an ex-tended period have

eliminated this step from their insulin injec-tion routine with no apparent

adverse effects.

PROMOTING HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED CARE

Teaching Patients Self-Care.

Adherence to

the therapeutic planis the most important goal of self-care the patient must

master. Patients who are having difficulty adhering to the diabetes treatment

plan must be approached with care and understand-ing. Using scare tactics (such

as threats of blindness or ampu-tation if the patient does not adhere to the

treatment plan) or making

the patient feel guilty is not productive and may inter-fere with establishing

a trusting relationship with the patient. Judgmental actions, such as asking

the patient if he or she has “cheated” on the diet, only promote feelings of

guilt and low self-esteem.

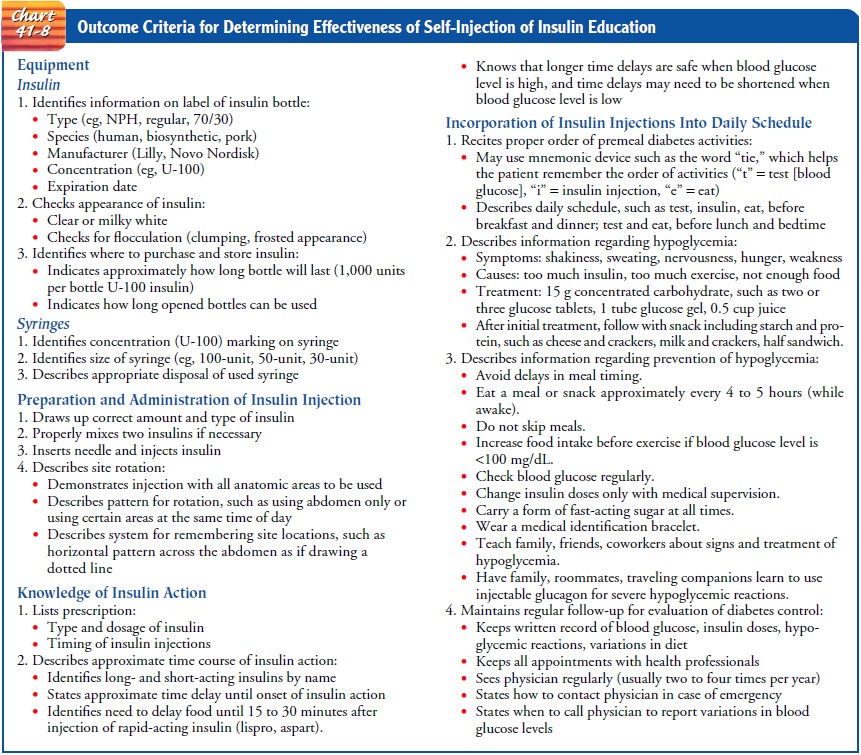

If

problems exist with glucose control or with the develop-ment of preventable

complications, it is important to distinguish among nonadherence, knowledge

deficit, and self-care deficit. It should not be assumed that problems with

diabetes management are related to nonadherence. The patient may simply have for-gotten

or never learned certain information. The problem may be correctable simply

through providing complete information and ensuring that the patient

comprehends the information. Chart 41-8 details how to evaluate the

effectiveness of self-injection of insulin.

If

knowledge deficit is not the problem, certain physical or emotional factors may

be impairing the patient’s ability to per-form self-care skills. For example,

decreased visual acuity may impair the patient’s ability to administer insulin

accurately, measure the blood glucose level, or inspect the skin and feet. In

addition, decreased joint mobility (especially in the elderly) im-pairs the

ability to inspect the bottom of the feet. Emotional factors such as denial of

the diagnosis or depression may impair the patient’s ability to carry out

multiple daily self-care mea-sures. In other circumstances, family, personal,

or work prob-lems may be of higher priority to the patient. The patient facing

competing demands for time and attention may benefit from assistance in

establishing priorities. It is also important to assess the patient for

infection or emotional stress that may lead to el-evated blood glucose levels

despite adherence to the treatment regimen.

The

following approaches by the nurse are helpful for pro-moting self-care

management skills:

•

Address any underlying factors (eg, knowledge

deficit, self-care deficit, illness) that may affect diabetic control.

•

Simplify the treatment regimen if it is too

difficult for the patient to follow.

•

Adjust the treatment regimen to meet patient

requests (eg, adjust diet or insulin schedule to allow increased flexi-bility

in meal content or timing).

•

Establish a specific plan or contract with the

patient with simple, measurable goals.

•

Provide positive reinforcement of self-care

behaviors per-formed instead of focusing on behaviors that were neglected (eg,

positively reinforce blood glucose tests that were per-formed instead of

focusing on the number of missed tests).

•

Help the patient to identify personal motivating

factors rather than focusing on wanting to please the doctor or nurse.

•

Encourage the patient to pursue life goals and

interests; dis-courage an undue focus on diabetes.

Continuing Care.

As discussed, continuing care of the patientwith diabetes is critical in managing and preventing complica-tions. The degree to which the client interacts with health care providers to obtain ongoing care depends on many factors. Age, socioeconomic level, existing complications, type of diabetes, and comorbid conditions all may dictate the frequency of follow-up vis-its. Many patients with diabetes may be seen by home health nurses for diabetic education, wound care, insulin preparation, or assistance with glucose monitoring. Even patients who achieve excellent glucose control and have no complications can expect to see their primary health care provider at least twice a year for ongoing evaluation.

In

addition to follow-up care with health professionals, par-ticipation in support

groups is encouraged for those who have had diabetes for many years as well as

those who are newly diag-nosed. Such participation may assist the patient and

family in coping with changes in lifestyle that occur with the onset of

diabetes and with its complications. Those who participate in support groups

often have an opportunity to share valuable in-formation and experiences and to

learn from others. Support groups provide an opportunity for discussion of

strategies to deal with diabetes and its management and to clarify and verify

infor-mation with the nurse or other health care professionals. Partici-pation

in support groups may help patients and their families to become more

knowledgeable about diabetes and its management and may promote adherence to the

management plan. Another very important role of the nurse is to remind the

patient about the importance of participating in other health promotion

activ-ities and recommended health screening.

Related Topics