Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetes Management: Exercise

EXERCISE

Benefits

Exercise

is extremely important in managing diabetes because of its effects on lowering

blood glucose and reducing cardiovascular risk factors. Exercise lowers the

blood glucose level by increasing the uptake of glucose by body muscles and by

improving insulin utilization. It also improves circulation and muscle tone.

Resis-tance (strength) training, such as weight lifting, can increase lean

muscle mass, thereby increasing the resting metabolic rate. These effects are

useful in diabetes in relation to losing weight, easing stress, and maintaining

a feeling of well-being. Exercise also alters blood lipid levels, increasing

levels of high-density lipoproteins and decreasing total cholesterol and

triglyceride levels. This is es-pecially important to the person with diabetes

because of the in-creased risk of cardiovascular disease (Creviston &

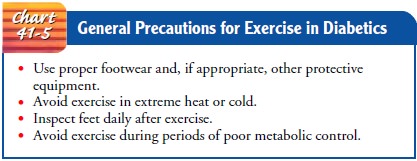

Quinn, 2001). General guidelines for exercise in diabetes are presented in

Chart 41-5.

Exercise Precautions

Patients

who have blood glucose levels exceeding 250 mg/dL (14 mmol/L) and who have

ketones in their urine should not begin exercising until the urine tests

negative for ketones and the blood glucose level is closer to normal.

Exercising with elevated blood glu-cose levels increases the secretion of

glucagon, growth hormone, and catecholamines. The liver then releases more

glucose, and the result is an increase in the blood glucose level (ADA,

Phys-ical Activity/Exercise and Diabetes Mellitus, 2003).

The physiologic decrease in circulating insulin that normally occurs with exercise cannot occur in patients treated with insulin. Initially, the patient who requires insulin should be taught to eat a 15-g carbohydrate snack (a fruit exchange) or a snack of com-plex carbohydrate with a protein before engaging in moderate ex-ercise, to prevent unexpected hypoglycemia. The exact amount of food needed varies from person to person and should be de-termined by blood glucose monitoring. Some patients find that they do not require a pre-exercise snack if they exercise within 1 to 2 hours after a meal. Other patients may require extra food re-gardless of when they exercise. If extra food is required, it need not be deducted from the regular meal plan.Another potential problem for patients who take insulin is hypoglycemia that occurs many hours after exercise. To avoid postexercise hypoglycemia, especially after strenuous or prolonged exercise, the patient may need to eat a snack at the end of the ex-ercise session and at bedtime and monitor the blood glucose level more frequently.

In addition, it may be necessary to have the pa-tient reduce the

dosage of insulin that peaks at the time of exer-cise. Patients who are

capable, knowledgeable, and responsible can learn to adjust their own insulin

doses. Others need specific instructions on what to do when they exercise.

Patients

participating in extended periods of exercise should test their blood glucose

levels before, during, and after the exercise pe-riod, and they should snack on

carbohydrates as needed to main-tain blood glucose levels (ADA, Physical

Activity/Exercise and Diabetes Mellitus, 2003). Other participants or observers

should be aware that the person exercising has diabetes, and they should know

what assistance to give if severe hypoglycemia occurs.

In

obese people with type 2 diabetes, exercise in addition to dietary management

both improves glucose metabolism and en-hances loss of body fat. Exercise

coupled with weight loss im-proves insulin sensitivity and may decrease the

need for insulin or oral agents. Eventually, the patient’s glucose tolerance

may return to normal. The patient with type 2 diabetes who is not taking

in-sulin or an oral agent may not need extra food before exercise.

Exercise Recommendations

People

with diabetes should exercise at the same time (preferably when blood glucose

levels are at their peak) and in the same amount each day. Regular daily

exercise, rather than sporadic exercise, should be encouraged. Exercise

recommendations must be altered as necessary for patients with diabetic

complications such as retinopathy, autonomic neuropathy, sensorimotor

neuropathy, and cardiovascular disease (ADA, Physical Activity/Exercise and

Dia-betes Mellitus, 2003). Increased blood pressure associated with ex-ercise

may aggravate diabetic retinopathy and increase the risk of a hemorrhage into

the vitreous or retina. Patients with ischemic heart disease risk triggering

angina or a myocardial infarction, which may be silent. Avoiding trauma to the

lower extremities is especially important in the patient with numbness related

to neuropathy.

In

general, a slow, gradual increase in the exercise period is en-couraged. For

many patients, walking is a safe and beneficial form of exercise that requires

no special equipment (except for proper shoes) and can be performed anywhere.

People with diabetes should discuss an exercise program with their physician

and un-dergo a careful medical evaluation with appropriate diagnostic studies

before beginning an exercise program (ADA, Physical Activity/Exercise and

Diabetes Mellitus, 2003; Creviston & Quinn, 2001; Flood & Constance,

2002).

For

patients who are older than 30 years and who have two or more risk factors for

heart disease, an exercise stress test is rec-ommended. Risk factors for heart

disease include hypertension, obesity, high cholesterol levels, abnormal

resting electrocardio-gram, sedentary lifestyle, smoking, male gender, and a

family his-tory of heart disease.

Gerontologic Considerations

Physical

activity that is consistent and realistic is beneficial to the elderly person

with diabetes. Physical fitness in the elderly popu-lation with diabetes may

lead to less chronic vascular disease and an improved quality of life (ADA,

Physical Activity/Exercise and Diabetes Mellitus, 2003). Advantages of exercise

in this popula-tion include a decrease in hyperglycemia, a general sense of

well-being, and the use of ingested calories, resulting in weight reduction.

Because there is an increased incidence of cardiovascu-lar problems in the

elderly, a pattern of gradual, consistent exer-cise should be planned that does

not exceed the patient’s physical capacity. Physical impairment from other

chronic diseases must also be considered. In some cases a physical therapy

evaluation may be warranted with the goal of determining exercises specific to

the patient’s needs and abilities. Tools such as the “Armchair Fitness” video

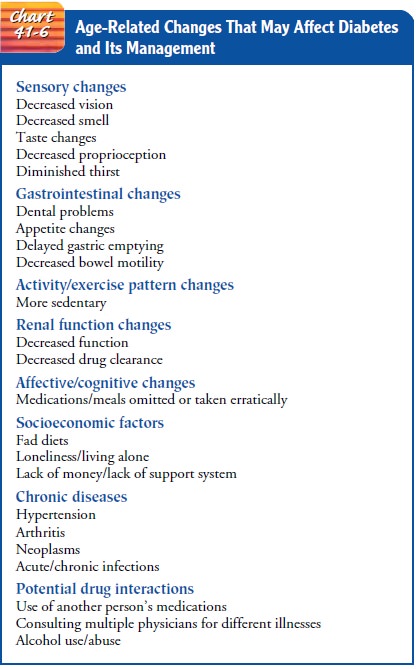

may be helpful. For more information about age-related changes that affect

diabetes management see Chart 41-6.

Related Topics