Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Diabetes Mellitus

Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar Nonketotic Syndrome - Acute Complications of Diabetes

HYPERGLYCEMIC

HYPEROSMOLAR NONKETOTIC SYNDROME

HHNS

is a serious condition in which hyperosmolarity and hyperglycemia predominate,

with alterations of the sensorium (sense of awareness). At the same time,

ketosis is minimal or absent. The basic biochemical defect is lack of effective

insulin (ie, insulin resistance). The patient’s persistent hyperglycemia causes

osmotic diuresis, resulting in losses of water and electrolytes. To maintain

osmotic equilibrium, water shifts from the intra-cellular fluid space to the

extracellular fluid space. With glucos-uria and dehydration, hypernatremia and

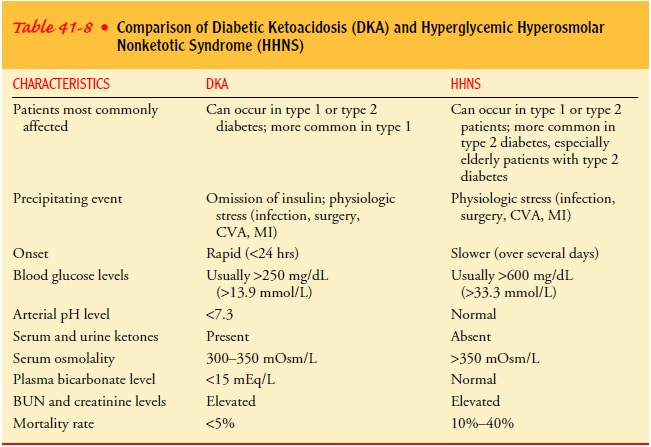

increased osmolarity occur. Table 41-8 compares DKA and HHNS.

This condition occurs most often in older people (ages 50 to 70 with no known history of diabetes or with mild type 2 dia-betes. HHNS can be traced to a precipitating event such as an acute illness (eg, pneumonia or stroke), medications that exacer-bate hyperglycemia (thiazides), or treatments, such as dialysis. The history includes days to weeks of polyuria with adequate fluid intake. What distinguishes HHNS from DKA is that keto-sis and acidosis do not occur in HHNS partly because of differ-ences in insulin levels. In DKA no insulin is present, and this promotes the breakdown of stored glucose, protein, and fat, which leads to the production of ketone bodies and ketoacidosis. In HHNS the insulin level is too low to prevent hyperglycemia (and subsequent osmotic diuresis), but it is high enough to pre-vent fat breakdown. Patients with HHNS do not have the ketosis-related GI symptoms that lead them to seek medical attention. Instead, they may tolerate polyuria and polydipsia until neuro-logic changes or an underlying illness (or family members or others) prompts them to seek treatment. Because of possible de-lays in therapy, hyperglycemia, dehydration, and hyperosmolarity may be more severe in HHNS (Quinn, 2001c).

Clinical Manifestations

The

clinical picture of HHNS is one of hypotension, profound dehydration (dry

mucous membranes, poor skin turgor), tachy-cardia, and variable neurologic

signs (eg, alteration of sensorium, seizures, hemiparesis). The mortality rate

ranges from 10% to 40%, usually related to an underlying illness.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Diagnostic

assessment includes a range of laboratory tests, in-cluding blood glucose,

electrolytes, BUN, complete blood count, serum osmolality, and arterial blood

gas analysis. The blood glu-cose level is usually 600 to 1,200 mg/dL, and the osmolality

ex-ceeds 350 mOsm/kg. Electrolyte and BUN levels are consistent with the

clinical picture of severe dehydration. Mental status changes, focal neurologic

deficits, and hallucinations are common secondary to the cerebral dehydration

that results from extreme hyperosmolality. Postural hypotension accompanies the

dehy-dration (ADA, Hyperglycemic Crises in Patients With Diabetes Mellitus,

2003).

Medical Management

The

overall approach to the treatment of HHNS is similar to that of DKA: fluid

replacement, correction of electrolyte imbalances, and insulin administration.

Because of the older age of the typi-cal patient with HHNS, close monitoring of

volume and elec-trolyte status is important for prevention of fluid overload,

heart failure, and cardiac dysrhythmias. Fluid treatment is started with 0.9%

or 0.45% NS, depending on the patient’s sodium level and the severity of volume

depletion. Central venous or arterial pres-sure monitoring guides fluid

replacement. Potassium is added to IV fluids when urinary output is adequate

and is guided by con-tinuous electrocardiographic monitoring and frequent

laboratory determinations of potassium.

Extremely

elevated blood glucose levels drop as the patient is rehydrated. Insulin plays

a less important role in the treatment of HHNS because it is not needed for

reversal of acidosis, as in DKA. Nonetheless, insulin is usually administered

at a continuous low rate to treat hyperglycemia, and replacement IV fluids with

dex-trose are administered (as in DKA) when the glucose level is de-creased to

the range of 250 to 300 mg/dL (13.8 to 16.6 mmol/L) (ADA, Hyperglycemic Crises

in Patients With Diabetes Mellitus, 2003).

Other

therapeutic modalities are determined by the underly-ing illness of the patient

and the results of continuing clinical and laboratory evaluation. Treatment is

continued until metabolic abnormalities are corrected and neurologic symptoms

clear. It may take 3 to 5 days for neurologic symptoms to resolve; thus,

treatment of HHNS usually continues well beyond the time when metabolic

abnormalities are resolved.

After

recovery from HHNS, many patients can control their diabetes with diet alone or

with diet and oral antidiabetic agents. Insulin may not be needed once the

acute hyperglycemic com-plication is resolved.

Nursing Management

Nursing

care of the patient with HHNS includes close monitor-ing of vital signs, fluid

status, and laboratory values. In addition, strategies are implemented to

maintain safety and prevent injury related to changes in the patient’s

sensorium secondary to HHNS. Fluid status and urine output are closely

monitored because ofthe high risk for renal failure secondary to severe

dehydration. In addition, the nurse must direct nursing care to the condition

that may have precipitated the onset of HHNS. Because HHNS tends to occur in

older patients, the physiologic changes that occur with aging make careful

assessment of cardiovascular, pulmonary, and renal function important

throughout the acute and recovery phases of HHNS (Quinn, 2001c).

Related Topics