Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetic Ketoacidosis - Acute Complications of Diabetes

DIABETIC

KETOACIDOSIS

DKA is

caused by an absence or markedly inadequate amount of insulin. This deficit in

available insulin results in disorders in the metabolism of carbohydrate,

protein, and fat. The three main clinical features of DKA are:

•

Hyperglycemia

•

Dehydration and electrolyte loss

•

Acidosis

Pathophysiology

Without

insulin, the amount of glucose entering the cells is re-duced and the liver

increases glucose production. Both factors lead to hyperglycemia. In an attempt

to rid the body of the excess glucose, the kidneys excrete the glucose along

with water and electrolytes (eg, sodium and potassium). This osmotic diuresis,

which is characterized by excessive urination (polyuria), leads to dehydration

and marked electrolyte loss. Patients with severe DKA may lose up to 6.5 liters

of water and up to 400 to 500 mEq each of sodium, potassium, and chloride over

a 24-hour period.

Another

effect of insulin deficiency or deficit is the breakdown of fat (lipolysis)

into free fatty acids and glycerol. The free fatty acids are converted into

ketone bodies by the liver. In DKA there is excessive production of ketone

bodies because of the lack of in-sulin that would normally prevent this from

occurring. Ketone bodies are acids; their accumulation in the circulation leads

to metabolic acidosis.

Three

main causes of DKA are decreased or missed dose of in-sulin, illness or

infection, and undiagnosed and untreated dia-betes (DKA may be the initial

manifestation of diabetes). An insulin deficit may result from an insufficient

dosage of insulin prescribed or from insufficient insulin being administered by

the patient. Errors in insulin dosage may be made by patients who are ill and

who assume that if they are eating less or if they are vomiting, they must

decrease their insulin doses. (Because illness, especially infections, may

cause increased blood glucose levels, pa-tients do not need to decrease their

insulin doses to compensate for decreased food intake when ill and may even

need to increase the insulin dose.)

Other

potential causes of decreased insulin include patient error in drawing up or

injecting insulin (especially in patients with visual impairments), intentional

skipping of insulin doses (especially in adolescents with diabetes who are

having difficulty coping with diabetes or other aspects of their lives), or

equipment problems (eg, occlusion of insulin pump tubing).

Illness

and infections are associated with insulin resistance. In response to physical

(and emotional) stressors, there is an increase in the level of “stress”

hormones—glucagon, epinephrine, nor-epinephrine, cortisol, and growth hormone.

These hormones promote glucose production by the liver and interfere with

glu-cose utilization by muscle and fat tissue, counteracting the effect of

insulin. If insulin levels are not increased during times of ill-ness and infection,

hyperglycemia may progress to DKA (Quinn, 2001c).

Clinical Manifestations

The

signs and symptoms of DKA are listed in Figure 41-8. The hyperglycemia of DKA

leads to polyuria and polydipsia (in-creased thirst). In addition, patients may

experience blurred vi-sion, weakness, and headache. Patients with marked

intravascular volume depletion may have orthostatic hypotension (drop in

sys-tolic blood pressure of 20 mm Hg or more on standing). Volume depletion may

also lead to frank hypotension with a weak, rapid pulse.

The ketosis and acidosis of DKA lead to GI symptoms such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. The abdominal pain and physical findings on examination can be so severe that they resemble an acute abdominal disorder that requires surgery. Patients may have acetone breath (a fruity odor), which occurs with elevated ketone levels.

In addition, hyperventilation (with very

deep, but not labored, respirations) may occur. These Kuss-maul respirations

represent the body’s attempt to decrease the aci-dosis, counteracting the

effect of the ketone buildup. In addition, mental status changes in DKA vary

widely from patient to pa-tient. Patients may be alert, lethargic, or comatose,

most likely depending on the plasma osmolarity (concentration of osmoti-cally

active particles).

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Blood

glucose levels may vary from 300 to 800 mg/dL (16.6 to 44.4 mmol/L). Some

patients have lower glucose values, and oth-ers have values of 1,000 mg/dL

(55.5 mmol/L) or more (usually depending on the degree of dehydration). The

severity of DKA is not necessarily related to the blood glucose level. Some

patients may have severe acidosis with modestly elevated blood glucose levels,

whereas others may have no evidence of DKA despite blood glucose levels of 400

to 500 mg/dL (22.2 to 27.7 mmol/L) (Quinn, 2001c).

Evidence

of ketoacidosis is reflected in low serum bicarbonate (0 to 15 mEq/L) and low

pH (6.8 to 7.3) values. A low PCO2 level (10 to 30 mm Hg) reflects respiratory

compensation (Kussmaul respirations) for the metabolic acidosis. Accumulation

of ketone bodies (which precipitates the acidosis) is reflected in blood and

urine ketone measurements.

Sodium

and potassium levels may be low, normal, or high, depending on the amount of

water loss (dehydration). Despite the plasma concentration, there has been a

marked total body de-pletion of these (and other) electrolytes. Ultimately,

these elec-trolytes will need to be replaced.

Elevated

levels of creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), he-moglobin, and hematocrit

may also be seen with dehydration. After rehydration, continued elevation in

the serum creatinine and BUN levels will be present in the patient with

underlying renal insufficiency.

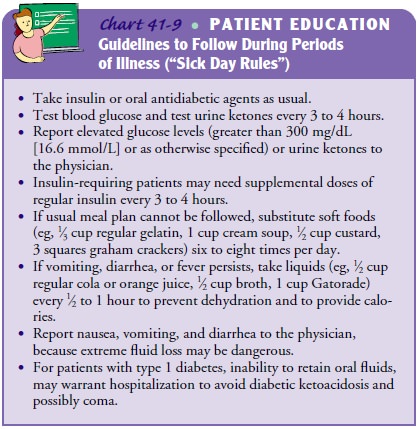

Prevention

For prevention

of DKA related to illness, patients must be taught “sick day” rules for

managing their diabetes when ill (Chart 41-9). The most important issue to

teach patients is not to eliminate insulin doses when nausea and vomiting

occur. Rather, they should take their usual insulin dose (or previously

prescribed special “sick day” doses) and then attempt to con-sume frequent

small portions of carbohydrates (including foods usually avoided, such as

juices, regular sodas, and gelatin). Drinking fluids every hour is important to

prevent dehydration. Blood glucose and urine ketones must be assessed every 3

to 4 hours.

If the

patient cannot take fluids without vomiting, or if ele-vated glucose or ketone

levels persist, the physician must be con-tacted. Patients are taught to have

available foods for use on sick days. In addition, a supply of urine test

strips (for ketone testing) and blood glucose test strips should be available.

Patients must know how to contact their physician 24 hours a day.

Diabetes self-management skills (including insulin adminis-tration and blood glucose testing) should be assessed to ensure that an error in insulin administration or blood glucose testing did not occur. Psychological counseling is recommended for pa-tients and family members if an intentional alteration in insulin dosing was the cause of the DKA

Medical Management

In

addition to treating hyperglycemia, management of DKA is aimed at correcting

dehydration, electrolyte loss, and acidosis (Quinn, 2001c).

REHYDRATION

In

dehydrated patients, rehydration is important for maintaining tissue perfusion.

In addition, fluid replacement enhances the ex-cretion of excessive glucose by

the kidneys. Patients may need up to 6 to 10 liters of IV fluid to replace

fluid losses caused by polyuria, hyperventilation, diarrhea, and vomiting.

Initially,

0.9% sodium chloride (normal saline) solution is ad-ministered at a rapid rate,

usually 0.5 to 1 L per hour for 2 to 3 hours. Half-strength normal saline

(0.45%) solution (also known as hypotonic saline solution) may be used for

patients with hyper-tension or hypernatremia or those at risk for heart

failure. After the first few hours, half-normal saline solution is the fluid of

choice for continued rehydration, if the blood pressure is sta-ble and the

sodium level is not low. Moderate to high rates of infusion (200 to 500 mL per

hour) may continue for several more hours. When the blood glucose level reaches

300 mg/dL (16.6 mmol/L) or less, the IV fluid may be changed to dextrose 5% in

water (D5W) to prevent a

precipitous decline in the blood glucose level (ADA, Hyperglycemic Crisis in

Patients with Dia-betes Mellitus, 2003).

Monitoring

fluid volume status involves frequent measure-ments of vital signs (including

monitoring for orthostatic changes in blood pressure and heart rate), lung

assessment, and monitor-ing intake and output. Initial urine output will lag

behind IV fluid intake as dehydration is corrected. Plasma expanders may be

necessary to correct severe hypotension that does not respond to IV fluid

treatment. Monitoring for signs of fluid overload is es-pecially important for

older patients, those with renal impair-ment, or those at risk for heart

failure.

RESTORING ELECTROLYTES

The

major electrolyte of concern during treatment of DKA is potassium. Although the

initial plasma concentration of potas-sium may be low, normal, or even high,

there is a major loss of potassium from body stores and an intracellular to

extracellular shift of potassium. Further, the serum level of potassium drops

during the course of treatment of DKA as potassium re-enters the cells;

therefore, it must be monitored frequently. Some of the fac-tors related to

treating DKA that reduce the serum potassium concentration include:

•

Rehydration, which leads to increased plasma volume

and subsequent decreases in the concentration of serum potas-sium. Rehydration

also leads to increased urinary excretion of potassium.

•

Insulin administration, which enhances the movement

of potassium from the extracellular fluid into the cells.

Cautious

but timely potassium replacement is vital to avoid dysrhythmias that may occur

with hypokalemia. Up to 40 mEq per hour may be needed for several hours.

Because extracellular potassium levels drop during DKA treatment, potassium

must be infused even if the plasma potassium level is normal.

Frequent

(every 2 to 4 hours initially) electrocardiograms and laboratory measurements

of potassium are necessary during the first 8 hours of treatment. Potassium

replacement is withheld only if hyperkalemia is present or if the patient is

not urinating.

REVERSING ACIDOSIS

Ketone

bodies (acids) accumulate as a result of fat breakdown. The acidosis that

occurs in DKA is reversed with insulin, which inhibits fat breakdown, thereby stopping acid buildup. Insulin is usually infused

intravenously at a slow, continuous rate (eg, 5 units per hour). Hourly blood

glucose values must be mea-sured. IV fluid solutions with higher concentrations

of glucose, such as normal saline (NS) solution (eg, D5NS or D50.45NS),

are administered when blood glucose levels reach 250 to 300 mg/dL (13.8 to 16.6

mmol/L) to avoid too rapid a drop in the blood glucose level.

Various IV mixtures of regular insulin may be

used. The nurse must convert hourly rates of insulin infusion (frequently

pre-scribed as “units per hour”) to IV drip rates. For example, if 100 units of

regular insulin are mixed in 500 mL 0.9% NS, then 1 unit of insulin equals 5

mL. Thus, an initial insulin infusion rate of 5 units per hour would equal 25

mL per hour. The insulin is often infused separately from the rehydration

solutions to allow frequent changes in the rate and content of rehydration

solutions.

Insulin

must be infused continuously until subcutaneous administration of insulin

resumes. Any interruption in administration may result in the reaccumulation of

ketone bodies and worsening acidosis. Even if blood glucose levels are dropping

to normal, the insulin drip must not be stopped; rather, the rate or

concentration of the dextrose infusion should be increased. Blood glucose

levels are usually corrected before the acidosis is corrected. Thus, IV insulin

may be continued for 12 to 24 hours until the serum bicarbonate level improves

(to at least 15 to 18 mEq/L) and until the patient can eat. In general,

bicarbonate infusion to correct severe acidosis is avoided during treatment of

DKA be-cause it precipitates further, sudden (and potentially fatal) de-creases

in serum potassium levels. Continuous insulin infusion is usually sufficient for

reversing DKA.

Nursing Management

Nursing

care of the patient with DKA focuses on monitoring fluid and electrolyte status

as well as blood glucose levels; admin-istering fluids, insulin, and other

medications; and preventing other complications such as fluid overload. Urine

output is mon-itored to ensure adequate renal function before potassium is

ad-ministered to prevent hyperkalemia. The electrocardiogram is monitored for

dysrhythmias indicating abnormal potassium lev-els. Vital signs, arterial blood

gases, and other clinical findings are recorded on a flow sheet. The nurse

documents the patient’s lab-oratory values and the frequent changes in fluids

and medications that are prescribed and monitors the patient’s responses. As

DKA resolves and the potassium replacement rate is decreased, the nurse makes

sure that:

•

There are no signs of hyperkalemia on the

electrocardio-gram (tall, peaked [or tented] T waves).

•

The laboratory values of potassium are normal or

low.

•

The patient is urinating (ie, no renal shutdown).

As the

patient recovers, the nurse reassesses the factors that may have led to DKA and

teaches the patient and family about strategies to prevent its recurrence

(Quinn, 2001c). If indicated,the nurse initiates a referral for home care to

ensure the patient’s continued recovery.

Related Topics