Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetes Management: Nutritional Management

NUTRITIONAL

MANAGEMENT

Nutrition,

diet, and weight control are the foundation of diabetes management. The most

important objective in the dietary and nutritional management of diabetes is

control of total caloric in-take to attain or maintain a reasonable body weight

and control of blood glucose levels. Success of this alone is often associated

with reversal of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes. However, achieving this goal

is not always easy. Because nutritional management of diabetes is so complex, a

registered dietitian who un-derstands diabetes management has the major

responsibility for this aspect of the therapeutic plan. However, the nurse and

all other members of the health care team need to be knowledgeable about

nutritional therapy and supportive of the patient who needs to implement

dietary and lifestyle changes (ADA, Expert Com-mittee on the Diagnosis and

Classification of Diabetes Mellitus, 2003). Nutritional management of the

diabetic patient includes the following goals (ADA, Evidence-Based Nutrition

Principles and Recommendations for the Treatment and Prevention of Diabetes and

Related Complications, 2003):

•

Providing all the essential food constituents (eg,

vitamins, minerals) necessary for optimal nutrition

•

Meeting energy needs

•

Achieving and maintaining a reasonable weight

•

Preventing wide daily fluctuations in blood glucose

levels, with blood glucose levels as close to normal as is safe and practical

to prevent or reduce the risk for complications

•

Decreasing serum lipid levels, if elevated, to

reduce the risk for macrovascular disease

For

patients who require insulin to help control blood glucose levels, maintaining

as much consistency as possible in the amount of calories and carbohydrates

ingested at different meal times is essential. In addition, consistency in the

approximate time inter-vals between meals, with the addition of snacks if

necessary, helps in preventing hypoglycemic reactions and in maintaining

overall blood glucose control.

For

obese diabetic patients (especially those with type 2 dia-betes), weight loss

is the key to treatment. (It is also a major factor in preventing diabetes.) In

general, overweight is considered to be a body mass index (BMI) of 25 to 29;

obesity is defined as 20% above ideal body weight or a BMI equal to or greater

than 30 (National Institutes of Health, 2000). BMI is a weight-to-height ratio

calculated by dividing body weight (in kilograms) by the square of the height

(in meters).. Obesity is associated with an increased resistance to in-sulin;

it is also a main factor in type 2 diabetes. Some obese patients who have type

2 diabetes and who require insulin or oral agents to control blood glucose

levels may be able to reduce or eliminate the need for medication through

weight loss. A weight loss as small as 10% of total weight may significantly

improve blood glucose lev-els. For obese diabetic patients who do not take insulin,

consistent meal content or timing is not as critical. Rather, decreasing the

overall caloric intake assumes more importance. However, meals should not be

skipped. Pacing food intake throughout the day places more manageable demands

on the pancreas.

Long-term

adherence to the meal plan is one of the most chal-lenging aspects of diabetes

management. For obese patients, it may be more realistic to restrict calories

only moderately. For those who have lost weight, maintaining the weight loss

may be difficult. To help these patients incorporate new dietary habits into

their lifestyles, diet education, behavioral therapy, group support, and

ongoing nutrition counseling are encouraged.

Meal Planning and Related Teaching

For all patients with diabetes, the meal plan must consider the pa-tient’s food preferences, lifestyle, usual eating times, and ethnic and cultural background. For patients using intensive insulin therapy, there may be greater flexibility in the timing and content of meals by allowing adjustments in insulin dosage for changes in eating and exercise habits.

Advances in insulin management (new insulin

analogs, insulin algorithms, insulin pumps) permit greater flexibility of

schedules than previously possible. This is in con-trast to the older concept

of maintaining a constant dose of in-sulin and requiring the patient to adjust

his or her schedule to the actions and duration of the insulin.

The

first step in preparing a meal plan is a thorough review of the patient’s diet

history to identify his or her eating habits and lifestyle. A thorough

assessment of the patient’s need for weight loss, gain, or maintenance is also

undertaken. In most instances, the person with type 2 diabetes requires weight

reduction.

In

teaching about meal planning, the clinical dietitian uses various educational

tools, materials, and approaches. Initial edu-cation addresses the importance

of consistent eating habits, the relationship of food and insulin, and the

provision of an individ-ualized meal plan. In-depth follow-up education then

focuses on management skills, such as eating at restaurants, reading food

labels, and adjusting the meal plan for exercise, illness, and special

occasions. The nurse plays an important role in communicating pertinent

information to the dietitian and reinforcing the patient’s understanding.

For

some patients, certain aspects of meal planning, such as the food exchange

system, may be difficult to learn. This may be related to limitations in the

patient’s intellectual level or to emotional issues, such as difficulty

accepting the diagnosis of di-abetes or feelings of deprivation and undue

restriction in eating. In any case, it helps to emphasize that using the

exchange sys-tem (or any food classification system) provides a new way of

thinking about food rather than a new way of eating. It is also important to

simplify information as much as possible and to provide opportunities for the

patient to practice and repeat ac-tivities and information.

CALORIC REQUIREMENTS

Calorie-controlled

diets are planned by first calculating the indi-vidual’s energy needs and

caloric requirements based on the pa-tient’s age, gender, height, and weight.

An activity element is then factored in to provide the actual number of

calories required for weight maintenance. To promote a 1- to 2-pound weight

loss per week, 500 to 1,000 calories are subtracted from the daily total. The

calories are distributed into carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, and a meal

plan is then developed.

The

1995 Exchange Lists for Meal Planning (ADA, 1995) are presented to the patient

using the appropriate amount of calories, with strict diet adherence as the

goal. Unfortunately, calorie-controlled diets are often confusing and difficult

to comply with. They require patients to measure precise portions and to eat

spe-cific foods and amounts at each meal and snack. In this instance,

developing a meal plan based on the individual’s usual eating habits and

lifestyle may be a more realistic approach to glucose control and weight loss

or weight maintenance. In both instances, the patient needs to work closely

with a registered dietitian to as-sess current eating habits and to achieve

realistic, individualized goals. The priority for a young patient with type 1

diabetes, for example, should be a diet with enough calories to maintain normal

growth and development. Some patients may be underweight at the onset of type 1

diabetes because of rapid weight loss from severe hyperglycemia. The goal with

these patients initially may be to provide a higher-calorie diet to regain lost

weight.

CALORIC DISTRIBUTION

A

diabetic meal plan also focuses on the percentage of calories to come from

carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. In general, carbohy-drate foods have the

greatest effect on blood glucose levels because they are more quickly digested

than other foods and are converted into glucose rapidly. Several decades ago it

was recommended that diabetic diets contain more calories from protein and fat

foods than from carbohydrates to reduce postprandial increases in blood glucose

levels. However, this resulted in a dietary intake inconsis-tent with the goal

of reducing the cardiovascular disease com-monly associated with diabetes (ADA,

Evidence-Based Nutrition Principles and Recommendations for the Treatment and

Preven-tion of Diabetes and Related Complications, 2003).

Carbohydrates.

The caloric

distribution currently recommendedis higher in carbohydrates than in fat and

protein. However, re-search into the appropriateness of a higher-carbohydrate

diet in patients with decreased glucose tolerance is ongoing, and

recom-mendations may change accordingly. Currently, the ADA and the American

Dietetic Association recommend that for all levels of caloric intake, 50% to

60% of calories should be derived from carbohydrates, 20% to 30% from fat, and

the remaining 10% to 20% from protein. These recommendations are also

consistent with those of the American Heart Association, American Cancer

Society, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (2000).

Carbohydrates

consist of sugars and starches. Little scientific evidence supports the belief

that sugars, such as sucrose, promote a greater blood glucose level compared to

starches (eg, rice, pasta, or bread). Although low glycemic index diets

(described below) may reduce postprandial glucose levels, there seem to be no

clear effects on outcomes (ADA, Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and

Classification of Diabetes Mellitus, 2003). Thus, the latest nutrition

guidelines recommend that all carbohydrates be eaten in moderation to avoid

high postprandial blood glucose levels (ADA, Exchange Lists for Meal Planning,

1995). Foods high in carbohydrates, such as sucrose, are not eliminated from

the diet but should be eaten in moderation (up to 10% of total calories) because

these foods are typically high in fat and lack vitamins, minerals, and fiber.

Carbohydrate

counting is another nutritional tool used for blood glucose management because

carbohydrates are the main nutrients in food that influence blood glucose

levels. This method provides flexibility in food choices, can be less

complicated to un-derstand than the diabetic food exchange list, and allows

more ac-curate management with multiple daily injections (insulin before each

meal). However, if carbohydrate counting is not used with other meal-planning

techniques, weight gain can result. A variety of methods are used to count

carbohydrates. When developing a diabetic meal plan using carbohydrate

counting, all food sources should be considered. Once digested, 100% of carbohydrates

are converted to glucose. However, approximately 50% of protein foods (meat,

fish, and poultry) are also converted to glucose.

One

method of carbohydrate counting includes counting grams of carbohydrates. If

target goals are not reached by count-ing carbohydrates alone, protein will be

factored into the calcu-lations. This is especially true if the meal consists

of only meat, fish, and non-starchy vegetables.

An

alternative to counting grams of carbohydrate is measur-ing servings or

choices. This method is used more often by peo-ple with type 2 diabetes. It is

similar to the food exchange list and emphasizes portion control of total

servings of carbohydrate at meals and snacks. One carbohydrate serving is

equivalent to 15 g of carbohydrate. Examples of one serving are an apple 2

inches in diameter and one slice of bread. Vegetables and meat are counted as

one third of a carbohydrate serving.

Although

carbohydrate counting is now commonly used for blood glucose management with

type 1 and type 2 diabetes, it is not a perfect system. All carbohydrates, to

some extent, affect the blood glucose to different degrees, regardless of

equivalent serving size.

Fats.

The recommendations regarding fat

content of the diabeticdiet include both reducing the total percentage of

calories from fat sources to less than 30% of the total calories and limiting

the amount of saturated fats to 10% of total calories. Additional

rec-ommendations include limiting the total intake of dietary choles-terol to

less than 300 mg/day. This approach may help to reduce risk factors such as

elevated serum cholesterol levels, which are as-sociated with the development

of coronary artery disease, the lead-ing cause of death and disability among

people with diabetes.

The

meal plan may include the use of some nonanimal sources of protein (eg, legumes

and whole grains) to help reduce saturated fat and cholesterol intake. In

addition, the amount of protein in-take may be reduced in patients with early

signs of renal disease.

Fiber.

The use of fiber in diabetic

diets has received increasedattention as researchers study the effects on

diabetes of a high-carbohydrate, high-fiber diet. This type of diet plays a

role in low-ering total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in

the blood. Increasing fiber in the diet may also improve blood glucose levels

and decrease the need for exogenous insulin.

There

are two types of dietary fibers: soluble and insoluble. Soluble fiber—in foods

such as legumes, oats, and some fruits— plays more of a role in lowering blood

glucose and lipid levels than does insoluble fiber, although the clinical

significance of this effect is probably small (ADA, Expert Committee on the

Diag-nosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus, 2003). Soluble fiber is thought

to be related to the formation of a gel in the GI tract. This gel slows stomach

emptying and the movement of food through the upper digestive tract. The

potential glucose-lowering effect of fiber may be caused by the slower rate of

glucose ab-sorption from foods that contain soluble fiber. Insoluble fiber is

found in whole-grain breads and cereals and in some vegetables. This type of

fiber plays more of a role in increasing stool bulk and preventing

constipation. Both insoluble and soluble fibers in-crease satiety, which is

helpful for weight loss.

One

risk involved in suddenly increasing fiber intake is that it may require

adjusting the dosage of insulin or oral agents to pre-vent hypoglycemia. Other

problems may include abdominal fullness, nausea, diarrhea, increased

flatulence, and constipation if fluid intake is inadequate. If fiber is added

to or increased in the meal plan, it should be done gradually and in

consultation with a dietitian. The 1995 Exchange Lists for Meal Planning (ADA,

1995) is an excellent guide for increasing fiber intake. Fiber-rich food

choices within the vegetable, fruit, and starch/bread exchanges are highlighted

in the lists.

FOOD CLASSIFICATION SYSTEMS

To

teach diet principles and to help patients in meal planning, several systems

have been developed in which foods are orga-nized into groups with common

characteristics, such as number of calories, composition of foods (ie, amount

of protein, fat, or carbohydrate in the food), or effect on blood glucose

levels.

Exchange Lists.

A commonly

used tool for nutritional manage-ment is the Exchange Lists for Meal Planning

(ADA, 1995).There

are six main exchange lists: bread/starch, vegetable, milk, meat, fruit, and

fat. Foods included on one list (in the amounts specified) contain equal

numbers of calories and are approxi-mately equal in grams of protein, fat, and

carbohydrate. Meal plans (tailored to the patient’s needs and preferences) are

based on a recommended number of choices from each exchange list. Foods on one

list may be interchanged with one another, allow-ing the patient to choose a

variety while maintaining as much consistency as possible in the nutrient

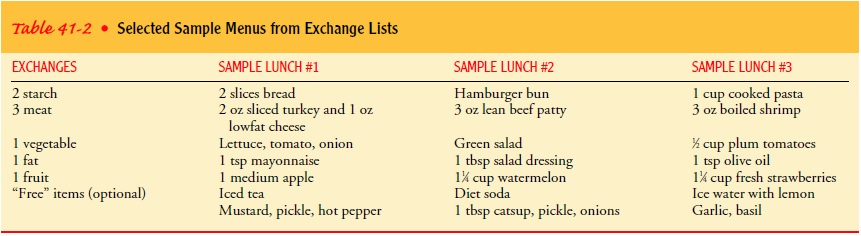

content of foods eaten. Table 41-2 presents three sample lunch menus that are

inter-changeable in terms of carbohydrate, protein, and fat content.

Exchange

list information on combination foods, such as pizza, chili, and casseroles,

and convenience foods, desserts, snack foods, and fast foods is available from

the ADA. Some food man-ufacturers and restaurants publish exchange lists that

describe their products as well. For more nutrition information, contact the

ADA.

The Food Guide Pyramid.

The Food

Guide Pyramid is anothertool used to develop meal plans. It is commonly used

for patients with type 2 diabetes who have a difficult time complying with a

calorie-controlled diet. The food pyramid consists of six food groups: (1)

bread, cereal, rice, and pasta; (2) fruits; (3) vegetables; (4) meat, poultry, fish, dry

beans, eggs, and nuts; (5) milk, yogurt, and cheese; and (6) fats, oils, and

sweets. The pyra-mid shape was chosen to emphasize that the foods in the

largest area, the base of the pyramid (starches, fruits, and vegetables), are

lowest in calories and fat and highest in fiber and should make up the basis of

the diet. For those with diabetes, as well as for the general population, 50%

to 60% of the daily caloric intake should be from these three groups. As one

moves up the pyramid, foods higher in fat (particularly saturated fat) are

illustrated; these foods should account for a smaller percentage of the daily

caloric intake. The very top of the pyramid comprises fats, oils, and sweets,

foods that should be used sparingly by people with diabetes to ob-tain weight

and blood glucose control and to reduce the risk for cardiovascular disease.

Reliance on the Food Guide Pyramid, however, may result in fluctuations in

blood glucose levels because high-carbohydrate foods may be grouped with

low-carbohydrate foods. The pyramid is appropriately used only as a first-step

teaching tool (Dixon, Cronin, & Krebs-Smith, 2001) for pa-tients learning

how to control food portions and how to identify which foods contain

carbohydrate, protein, and fat.

Glycemic Index.

One of the

main goals of diet therapy in dia-betes is to avoid sharp, rapid increases in

blood glucose levels after food is eaten. The term “glycemic index” is used to

describe how much a

given food raises the blood glucose level compared with an equivalent amount of

glucose; however, the effects on blood glucose levels and on long-term patient

outcomes have been ques-tioned (ADA, Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and

Classifi-cation of Diabetes Mellitus, 2003). Although more research is

necessary, the following guidelines can be helpful when making dietary

recommendations:

•

Combining starchy foods with protein- and

fat-containing foods tends to slow their absorption and lower the glycemic

response.

•

In general, eating foods that are raw and whole

results in a lower glycemic response than eating chopped, puréed, or cooked

foods.

•

Eating whole fruit instead of drinking juice

decreases the glycemic response because fiber in the fruit slows absorption.

•

Adding foods with sugars to the diet may produce a

lower glycemic response if these foods are eaten with foods that are more

slowly absorbed.

Patients

can create their own glycemic index by monitoring their blood glucose level

after ingesting a particular food. This can help patients improve blood glucose

levels through individualized manipulation of the diet. Many patients who use

frequent mon-itoring of blood glucose levels can use this information to adjust

their insulin doses for variations in food intake.

Other Dietary Concerns

ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION

Patients with diabetes do not need to give up alcoholic beverages entirely, but patients and health care professionals need to be aware of the potential adverse effects of alcohol specific to diabetes. In general, the same precautions regarding the use of alcohol by peo-ple without diabetes should be applied to patients with diabetes. Moderation is recommended. The main danger of alcohol con-sumption by a diabetic patient is hypoglycemia, especially for pa-tients who take insulin. Alcohol may decrease the normal physiologic reactions in the body that produce glucose (gluconeo-genesis). Thus, if a diabetic patient takes alcohol on an empty stom-ach, there is an increased likelihood that hypoglycemia will develop. In addition, excessive alcohol intake may impair the pa-tient’s ability to recognize and treat hypoglycemia and to follow a prescribed meal plan to prevent hypoglycemia. To reduce the risk of hypoglycemia, the patient should be cautioned to eat while drinking alcohol (ADA, Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus, 2003).

For

the person with type 2 diabetes treated with the sulfonylurea agent

chlorpropamide (Diabinese), a potential side effect of alcohol consumption is a

disulfiram (Antabuse) type of reaction, which in-volves facial flushing,

warmth, headache, nausea, vomiting, sweat-ing, or thirst within minutes of

consuming alcohol. The intensity of the reaction depends on the amount of

alcohol consumed; the reaction seems to be less common with other

sulfonylureas.

Alcohol

consumption may lead to excessive weight gain (from the high caloric content of

alcohol), hyperlipidemia, and elevated glucose levels (especially with mixed

drinks and liqueurs).

Patient

teaching regarding alcohol intake must emphasize moderation in the amount of

alcohol consumed. Lower-calorie or less sweet drinks, such as light beer or dry

wine, and food intake along with alcohol consumption are advised. For patients

with type 2 diabetes especially, incorporating the calories from alcohol into

the overall meal plan is important for weight control.

SWEETENERS

Using

sweeteners is acceptable for patients with diabetes, espe-cially if it assists

in overall dietary adherence. Moderation in the amount of sweetener used is

encouraged to avoid potential ad-verse effects. There are two main types of

sweeteners: nutritive and non-nutritive. The nutritive sweeteners contain

calories, and the non-nutritive sweeteners have few or no calories in the

amounts normally used.

Nutritive

sweeteners include fructose (fruit sugar), sorbitol, and xylitol. They are not calorie-free;

they provide calories in amounts similar to those in sucrose (table sugar).

They cause less elevation in blood sugar levels than sucrose and are often used

in “sugar-free” foods. Sweeteners containing sorbitol may have a lax-ative

effect.

Non-nutritive

sweeteners have minimal or no calories. They are used in food products and are

also available for table use. They produce minimal or no elevation in blood

glucose levels and have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration as

safe for people with diabetes. Saccharin contains no calories. Aspartame

(NutraSweet) is packaged with dextrose; it contains 4 calories per packet and

loses sweetness with heat. Acesulfame-K (Sunnette) is also packaged with

dextrose; it contains 1 calorie per packet. Sucralose (Splenda) is a newer

non-nutritive, high-intensity sweet-ener that is about 600 times sweeter than

sugar. The Food and Drug Administration has approved it for use in baked goods,

nonalcoholic beverages, chewing gum, coffee, confections, frost-ings, and

frozen dairy products.

MISLEADING FOOD LABELS

Foods

labeled “sugarless” or “sugar-free” may still provide calo-ries equal to those

of the equivalent sugar-containing products if they are made with nutritive

sweeteners. Thus, for weight loss, these products may not always be useful. In

addition, patients must not consider them “free” foods to be eaten in unlimited

quantity, because they may elevate blood glucose levels.

Foods

labeled “dietetic” are not necessarily reduced-calorie foods. They may be lower

in sodium or have other special dietary uses. Patients are advised that foods

labeled “dietetic” may still contain significant amounts of sugar or fat.

Patients

must also be taught to read the labels of “health foods”—especially

snacks—because they often contain carbohy-drates such as honey, brown sugar,

and corn syrup. In addition, these supposedly healthy snacks frequently contain

saturated veg-etable fats (eg, coconut or palm oil), hydrogenated vegetable

fats, or animal fats, which may be contraindicated in patients with elevated

blood lipid levels.

Related Topics