Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Eye and Vision Disorders

Glaucoma

Glaucoma

Glaucoma is a group of ocular conditions

characterized by optic nerve damage. The optic nerve damage is related to the

IOP caused by congestion of aqueous humor in the eye. There is a range of

pressures that have been considered “normal” but that may be associated with

vision loss in some patients. Glaucoma is one of the leading causes of

irreversible blindness in the world and is the leading cause of blindness among

adults in the United States. It is estimated that at least 2 million Americans

have glau-coma and that 5 to 10 million more are at risk (Margolis et al.,

2002). Glaucoma is more prevalent among people older than 40 years of age, and

the incidence increases with age. It is also more prevalent among men than

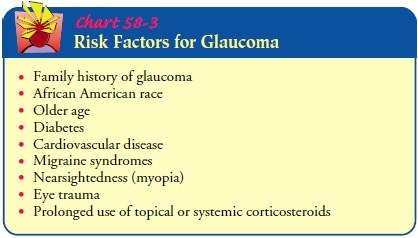

women and in the African American and Asian populations (Chart 58-3). There is

no cure for glaucoma, but research continues.

Aqueous Humor and Intraocular Pressure

Aqueous humor flows between the iris and the lens,

nourishing the cornea and lens. Most (90%) of the fluid then flows out of the

anterior chamber, draining through the spongy trabecular meshwork into the

canal of Schlemm and the episcleral veins (Fig. 58-7). About 10% of the aqueous

fluid exits through the cil-iary body into the suprachoroidal space and then

drains into the venous circulation of the ciliary body, choroid, and sclera.

Unim-peded outflow of aqueous fluid depends on an intact drainage sys-tem and

an open angle (about 45 degrees) between the iris and the cornea. A narrower

angle places the iris closer to the trabecu-lar meshwork, diminishing the angle.

The amount of aqueous humor produced tends to decrease with age, in systemic

diseases such as diabetes, and in ocular inflammatory conditions.

IOP is determined by the rate of aqueous

production, the re-sistance encountered by the aqueous humor as it flows out of

the passages, and the venous pressure of the episcleral veins that drain into

the anterior ciliary vein. When aqueous fluid production and drainage are in

balance, the IOP is between 10 and 21 mm Hg. When aqueous fluid is inhibited

from flowing out, pressure builds up within the eye. Fluctuations in IOP occur

with time of day, exertion, diet, and medications. It tends to increase with

blinking, tight lid squeezing, and upward gazing. Systemic con-ditions such as

hypertension and intraocular conditions such as uveitis and retinal detachment

have been associated with elevated IOP. Exposure to cold weather, alcohol, a

fat-free diet, heroin, and marijuana have been found to lower IOP.

Pathophysiology

There are two accepted theories regarding how

increased IOP damages the optic nerve in glaucoma. The direct mechanical

the-ory suggests that high IOP damages the retinal layer as it passes through

the optic nerve head. The indirect ischemic theory sug-gests that high IOP

compresses the microcirculation in the optic nerve head, resulting in cell

injury and death. Some glaucomas appear as exclusively mechanical, and some are

exclusively is-chemic types. Typically, most cases are a combination of both.

Regardless of the cause of damage, glaucomatous

changes typ-ically evolve through clearly discernible stages:

Initiating events: precipitating factors include illness, emo-tional stress, congenital narrow angles, long-term use of corticosteroids, and mydriatics (ie, medications causing pupillary dilation). These events lead to the second stage.

Structural

alterations in the aqueous outflow system: tissueand cellular changes caused by factors that affect

aqueous humor dynamics lead to structural alterations and to the third stage.

Functional

alterations: conditions such as

increased IOP orimpaired blood flow create functional changes that lead to the

fourth stage.

Optic

nerve damage: atrophy of the optic

nerve is charac-terized by loss of nerve fibers and blood supply, and this fourth

stage inevitably progresses to the fifth stage.

Visual

loss: progressive loss of

vision is characterized byvisual field defects.

Classification of Glaucoma

There are several types of glaucoma. Whether

glaucoma is known as open-angle or angle-closure glaucoma depends on which

mech-anisms cause impaired aqueous outflow. Glaucoma can be primary or

secondary, depending on whether associated factors con-tribute to the rise in

IOP.

Although glaucoma classification is changing as

knowledge in-creases, current clinical forms of glaucoma are open-angle

glau-comas, angle-closure glaucomas (also called pupillary block), congenital

glaucomas, and glaucomas associated with other con-ditions, such as

developmental anomalies, corticosteroid use, and other ocular conditions. The

two common clinical forms of glau-coma encountered in adults are open-angle and

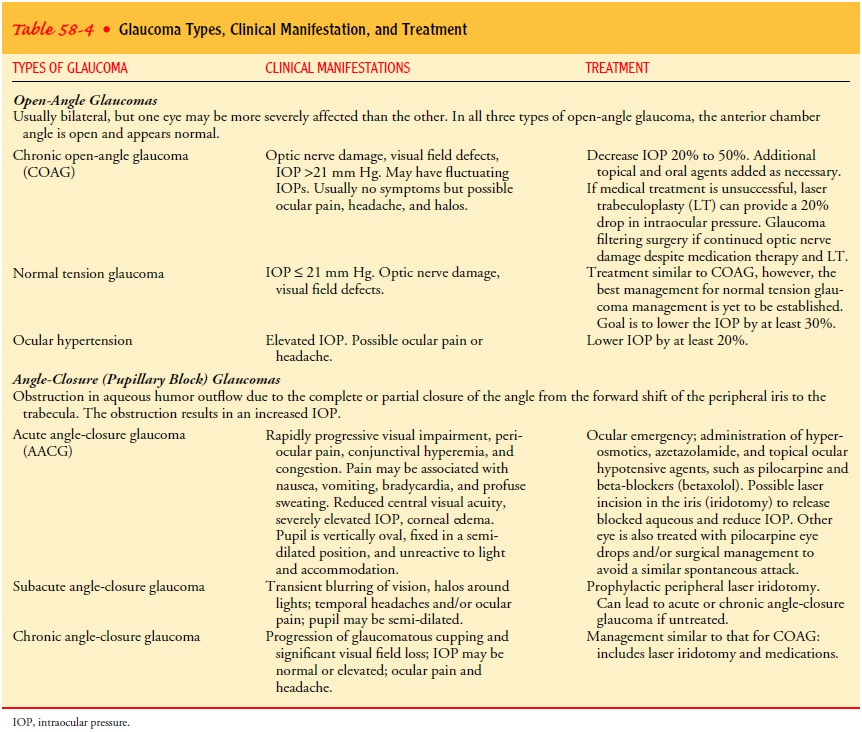

angle-closure glaucoma. Table 58-4 explains the general characteristics of the

different types of open-angle and angle-closure glaucomas.

Clinical Manifestations

Glaucoma is often called the silent thief of sight because most pa-tients are unaware that they have the disease until they have ex-perienced visual changes and vision loss. The patient may not seek health care until he or she experiences blurred vision or “halos” around lights, difficulty focusing, difficulty adjusting eyes in low lighting, loss of peripheral vision, aching or discomfort around the eyes, and headache.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

The

purpose of a glaucoma workup is to establish the diagnostic category, assess

the optic nerve damage, and formulate a treat-ment plan. The patient’s ocular

and medical history must be de-tailed to investigate the history of

predisposing factors. There are four major types of examinations used in

glaucoma evaluation, diagnosis, and management: tonometry to measure the IOP,

ophthalmoscopy to inspect the optic nerve, gonioscopy to exam-ine the

filtration angle of the anterior chamber, and perimetry to assess the visual

fields.

The

changes in the optic nerve significant for the diagnosis of glaucoma are pallor

and cupping of the optic nerve disc. The pal-lor of the optic nerve is caused

by a lack of blood supply that re-sults from cellular destruction. Cupping is

characterized by exaggerated bending of the blood vessels as they cross the

optic disc, resulting in an enlarged optic cup that appears more basin-like

compared with a normal cup. The progression of cupping in glaucoma is caused by

the gradual loss of retinal nerve fibers ac-companied by the loss of blood

supply, resulting in increased pal-lor of the optic disc.

As the optic nerve damage increases, visual perception in the area is lost. The localized areas of visual loss (ie, scotomas) represent loss of retinal sensitivity and are measured and mapped by perime-try. The results are mapped on a graph. In patients with glaucoma, the graph has a distinct pattern that is different from other ocular diseases and is useful in establishing the diagnosis. Figure 58-8 shows the progression of visual field defects caused by glaucoma.

Medical Management

The

aim of all glaucoma treatment is prevention of optic nerve damage through

medical therapy, laser or nonlaser surgery, or a combination of these approaches.

Lifelong therapy is almost al-ways necessary because glaucoma cannot be cured.

Although treatment cannot reverse optic nerve damage, further damage can be

controlled. The treatment goal is to maintain an IOP within a range unlikely to

cause further damage.

The

initial target for IOP among patients with elevated IOP and those with

low-tension glaucoma with progressive visual field loss is typically set at 30%

lower than the current pressure. The patient is monitored for the stability of

the optic nerve. If there is evidence of progressive damage, the target IOP is

again lowered until the optic nerve shows stability.

Treatment

focuses on achieving the greatest benefit at the least risk, cost, and

inconvenience to the patient. All treatment options have potential

complications, especially surgery, which yields the best success rates. In the

United States, medical management is the common approach, and surgical

management is the last re-sort. In Great Britain, the initial treatment of

choice is surgery (Fechtner & Singh, 2001).

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Medical

management of glaucoma relies on systemic and topical ocular medications that

lower IOP. Periodic follow-up examina-tions are essential to monitor IOP,

appearance of the optic nerve, visual fields, and side effects of medications.

In considering a therapeutic regimen, the ophthalmologist aims for the greatest

ef-fectiveness with the least side effects, inconvenience, and cost. Therapy

takes into account the patient’s health and stage of glau-coma. Comfort,

affordability, convenience, lifestyle, and person-ality are factors to consider

in the patient’s compliance with the medical regimen.

The

patient is usually started on the lowest dose of topical medication and then

advanced to increased concentrations until the desired IOP level is reached and

maintained. Because of their efficacy, minimal dosing (can be used once each

day), and low cost, beta-blockers are the preferred initial topical

medications. One eye is treated first, with the other eye used as a control in

de-termining the efficacy of the medication; once efficacy has been

established, treatment of the fellow eye is started. If the IOP is el-evated in

both eyes, both are treated. When results are not satis-factory, a new

medication is substituted. The main markers of the efficacy of the medication

in glaucoma control are lowering of the IOP to the target pressure, appearance

of the optic nerve head, and the visual field.

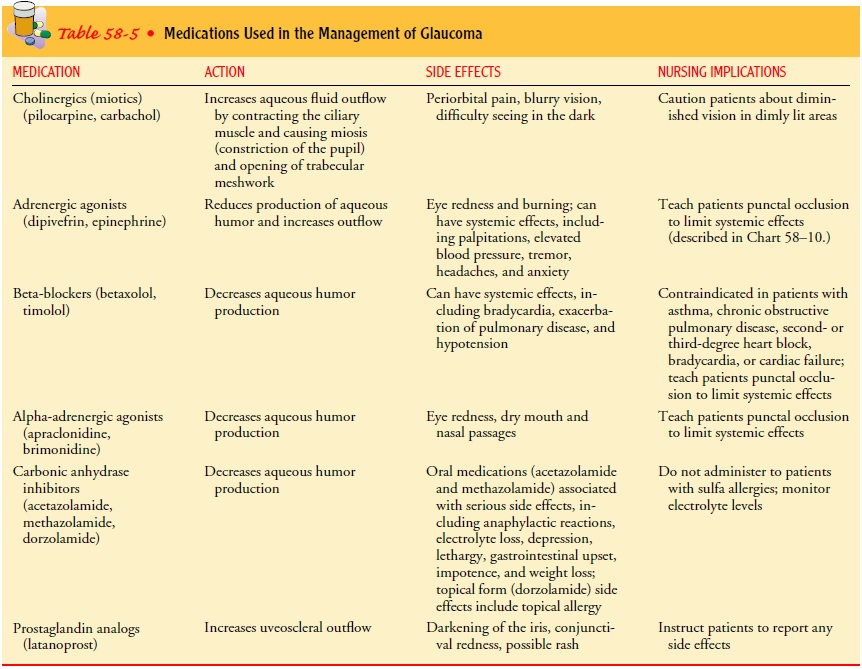

Several

types of ocular medications are used to treat glaucoma (Table 58-5), including miotics (ie, cause pupillary

constriction), adrenergic agonists (ie, sympathomimetic agents), beta-blockers,

alpha2-agonists (ie, adrenergic

agents), carbonic anhydrase in-hibitors, and prostaglandins. Cholinergics (ie,

miotics) increase the outflow of the aqueous humor by affecting ciliary muscle

con-traction and pupil constriction, allowing flow through a larger opening

between the iris and the trabecular meshwork. Adrener-gic agonists increase

aqueous outflow but primarily decrease aqueous production with an action

similar to beta-blockers and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

In laser trabeculoplasty for glaucoma, laser burns are applied to the inner surface of the trabecular meshwork to open the intra-trabecular spaces and widen the canal of Schlemm, thereby promoting outflow of aqueous humor and decreasing IOP.

The pro-cedure is indicated when IOP is inadequately controlled by

med-ications; it is contraindicated when the trabecular meshwork cannot be

fully visualized because of narrow angles. A serious complication of this

procedure is a transient rise in IOP (usually 2 hours after surgery) that may

become persistent. IOP assess-ment in the immediate postoperative period is

essential.

In laser

iridotomy for pupillary block glaucoma, an opening is made in the iris to

eliminate the pupillary block. Laser iridotomy is contraindicated in patients

with corneal edema, which inter-feres with laser targeting and strength.

Potential complications are burns to the cornea, lens, or retina; transient

elevated IOP; closure of the iridotomy; uveitis; and blurring. Pilocarpine is

usu-ally prescribed to prevent closure of the iridotomy.

Filtering

procedures for chronic glaucoma are

used to create anopening or fistula in the trabecular meshwork to drain aqueous

humor from the anterior chamber to the subconjunctival space into a bleb,

thereby bypassing the usual drainage structures. This allows the aqueous humor

to flow and exit by different routes (ie, absorption by the conjunctival

vessels or mixing with tears). Trabeculectomy

is the standard filtering technique used to removepart of the trabecular

meshwork. Complications include hemor-rhage, an extremely low (hypotony) or

elevated IOP, uveitis, cataracts, bleb failure, bleb leak, and endophthalmitis.

Unlike other surgical procedures, the filtering procedure’s goal in glaucoma

treatment is to achieve incomplete healing of the surgical wound. The outflow

of aqueous humor in a newly created drain-age fistula is circumvented by the

granulation of fibrovascular tissue or scar tissue formation on the surgical

site. Scarring is in-hibited by using antifibrosis agents such as the

antimetabolites fluorouracil (Efudex) and mitomycin (Mutamycin). Like all

anti-neoplastic agents, they require special handling procedures before,

during, and after the procedure. Fluorouracil can be administered

intraoperatively and by subconjunctival injection during follow-up; mitomycin

is much more potent and is administered only intraoperatively.

Drainage implants or shunts are

open tubes implanted in theanterior chamber to shunt aqueous humor to an

attached plate in the conjunctival space. A fibrous capsule develops around the

episcleral plate and filters the aqueous humor, thereby regulating the outflow

and controlling IOP.

Nursing Management

TEACHING PATIENTS ABOUT GLAUCOMA CARE

The medical and surgical management of glaucoma

slows the progression of glaucoma but does not cure it. The lifelong

thera-peutic regimen mandates patient education. The nature of the disease and

the importance of strict adherence to the medication regimen must be explained

to help ensure compliance. A thor ough patient interview is essential to

determine systemic condi-tions, current systemic and ocular medications, family

history, and problems with compliance to glaucoma medications. Then the

medication program can be discussed, particularly the inter-actions of

glaucoma-control medications with other medications. For example, the diuretic

effect of acetazolamide has an additive effect on the diuretic effects of other

antihypertensive medica-tions and can result in hypokalemia. The effects of

glaucoma-control medications on vision must also be explained. Miotics and

sympathomimetics result in altered focus; therefore, patients need to be

cautious in navigating their surroundings. Informa-tion about instilling ocular

medication and preventing systemic absorption with punctal occlusion is

described in the section on ophthalmic medications.

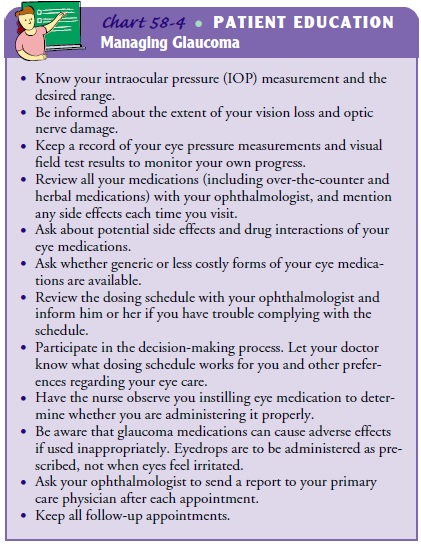

Nurses in all settings encounter patients with

glaucoma. Even patients with long-standing disease and those with glaucoma as a

secondary diagnosis should be assessed for knowledge level and compliance with

the therapeutic regimen. Chart 58-4 contains points to review with glaucoma

patients.

CONTINUING GLAUCOMA CARE AT HOME

For patients with severe glaucoma and impaired

function, refer-ral to services that assist the patient in performing customary

ac-tivities may be needed. The loss of peripheral vision impairs mobility the

most. These patients need to be referred to low-vision and rehabilitation

services. Patients who meet the criteria for legal blindness should be offered

referrals to agencies that assist in obtaining federal assistance.

Reassurance and emotional support are important aspects of care. A lifelong disease involving a possible loss of sight has psy-chological, physical, social, and vocational ramifications.

The family must be integrated into the plan of care,

and because the disease has a familial tendency, family members should be

en-couraged to undergo examinations at least once every 2 years to detect

glaucoma early.

Related Topics