Chapter: Psychology: Consciousness

Why Do We Dream ?

WHY DO WE DREAM ?

In Western cultures, dreams have

historically been considered prophetic; across the centuries, dream analysis

has been a standard practice among fortune-tellers. Moreover, people around the

world regard their dreams as meaningful.

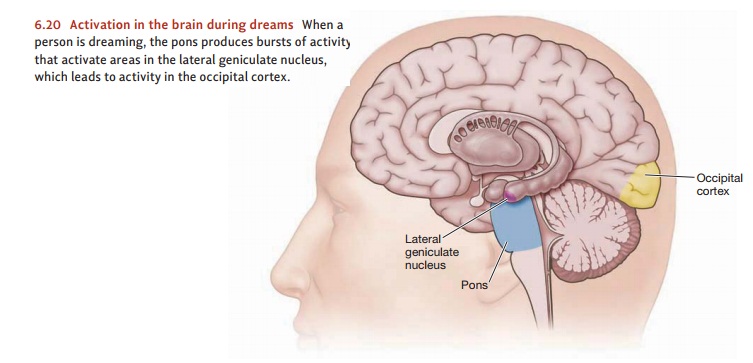

In one study, people in countries as diverse as the United States, India, and

South Korea said they thought dreams “reveal hidden truths” by allowing

“emotions buried in the unconscious” to come to the surface (Figure 6.19;

Morewedge & Norton, 2009).

Apparently, then, people are

ready to endorse a proposal similar to the one suggested by Sigmund Freud in

his book, The Interpretation of Dreams

(1900). Freud argued that we all harbor a host of primitive and forbidden

wishes, but we protect ourselves by keeping these wishes out of our conscious

thoughts. In dreams, however, our self-censorship is relaxed just a bit,

allowing these impulses to break through into our awareness. Even in sleep,

though, some of our efforts at self-protection continue; so the forbidden

impulses can enter our dreams only in a disguised form. In Freud’s view,

therefore, the characters that we observe in our dreams, and the actions we

witness, are merely the manifest content

of the dream—the content we’re able to experience directly. The real meaning of

the dream, in contrast, lies in the dream’s latent

content—the actual wishes and desires that are being expressed

(symbolically) through the manifest content.

Is this proposal correct? At the

most general level, Freud is suggesting that dreams usually reflect the

sleeper’s ongoing emotional concerns; and he was surely correct about this

broad point. Thus if you’ve narrowly avoided a car crash, you’re likely to

dream about collisions and other accidents; if you’re worried about an upcoming

exam, you may well end up dreaming about exams or other forms of evaluation.

Indeed, in the weeks following the September 11, 2001, attacks, many residents

of New York City reported dreams about terrorist attacks (Galea et al., 2002).

There is, however, little

evidence to support Freud’s more ambitious claim that dream content should be

understood in terms of thinly disguised wishes (S. Fisher & Greenberg,

1977, 1996). As one large concern, Freud’s own evidence was based on his interpretation of dreams, and it’s

difficult (some would say impossible) to know if theinterpretations were

correct or not. There’s surely nothing inevitable about Freud’s

interpretations; indeed, some of his followers offered very different

interpretations of the same dreams that Freud himself had analyzed. This

highlights just how uncertain the interpretation process is, and it reveals

that the “evidence” Freud offered for his view is not persuasive in the way

science requires.

Modern scholars have therefore turned

to a different hypothesis about dream content, one that does not view dreams as

having a specific function of their own. Instead, dreams may be just a

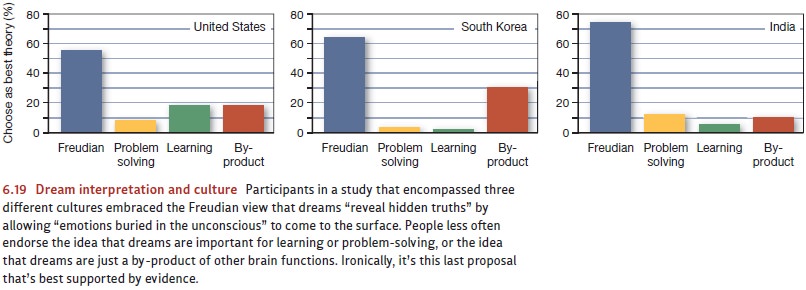

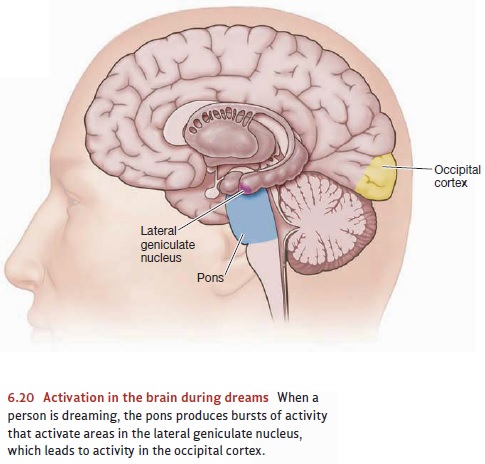

by-product of other brain activities. Specifically, the activation-synthesishypothesis begins with the fact that during REM

sleep, the pons (a structure in the brainstem) produces bursts of neural

activity that in turn activate areas in the lateral genicu-late nucleus—an

important processing center for visual information. This activity then

leads to activity in the

occipital cortex—the brain area that carries out most of the analy-sis of

visual input. Researchers refer to this neural activity as PGO waves because it involves the pons, the geniculate, and

the occipital areas (Figure 6.20).

These waves are the “activation” part of activation synthesis and give us an

immediate explanation for why dreams are filled with vivid visual images—the

result of neural activity in brain areas ordinarily involved in processing

visual information.

But why do certain images come to

mind? The key here is that these brain areas have been primed by other neural

activity, activity caused by the person’s recent experiences as well as shaped

by their recurrent thoughts. It is therefore the combination of PGO activity

and this priming that brings certain images—either from the previous day or

reflecting broader themes—into awareness. There is, however, no orderly

narrative linking the images that come to mind; instead, the sequence is

essentially random. Still, the brain does what it can to assemble these images

into a coherent plot—this is the “synthesis” part of the activation-synthesis

hypothesis. Some of this assembly takes place during the dream itself, but some

probably occurs once the person is awake and trying to recall the dream.

Let’s be clear, though, that the

set of ideas activated in the sleeper’s brain is likely to be something of a

hodgepodge, since the sequence of these ideas is not constrained by perceptual

input or a cohesive set of goals. As a result, the effort toward coherence will

often be only partially successful, and this is why dreams are often

unrealistic: The shaky plot line is the best the brain can do in weaving

together the odd assembly of images that bubble into awareness during REM

sleep.

Other aspects of brain activity

also play a role in shaping dream content. Several studies have monitored the

pattern of blood flow through people’s brains while they were dreaming. The

data show high levels of activity in the limbic system, a set of structures in

the brain—including the amygdala—associated with perceiving and regulating

emotion; this result obviously fits with the emotional character of many dreams

(Schwartz & Maquet, 2002). The data also show considerable neural activity

in the motor cortex—as if the neurons were trying to initiate movements,

although other mechanisms (in the brain stem) intercept the signals from the

motor cortex and ensure the movements never occur. (This is why, as we

mentioned earlier, the body is impressively immobile during REM sleep.)

Brain scans also show diminished activity during sleep in some

brain areas. These include the prefrontal cortex, a brain region often

associated with planning and intelligent analysis. This finding may give us a

further clue about why dreams often have peculiar content: When we’re in the

dream state, the parts of the brain needed to assemble the story elements into

an intelligible narrative aren’t fully engaged.

Related Topics