Chapter: Psychology: Consciousness

Drug-Induced Changes in Consciousness: Stimulants

STIMULANTS

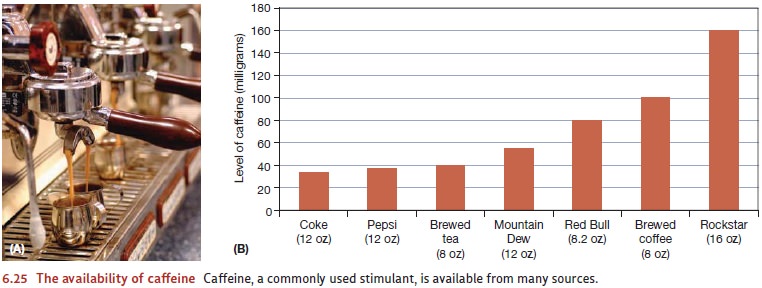

For medical or recreational

reasons, people sometimes turn to stimulants—drugs

that stimulate the nervous system and

broadly increase the level of bodily arousal. These drugsraise the person’s

blood pressure, increase heart and breathing rate, and certainly increase

overall alertness. Like the depressants, some of the stimulants are freely

available; the most obvious example is caffeine,

which is found in coffee, tea, various colas, and some of the new energy drinks

(Figure 6.25). Other stimulants are more powerful, less available, and in many

cases illegal; the list includes cocaine and various forms of amphetamine, such

as d-amphetamine, methamphetamine, and MDMA (also known as ecstasy). This list

is surely partial, however, because new stimulants are often synthesized to

supply an eager market.

Some stimulants have, or once

had, legitimate uses. Amphetamines, for example, are sometimes prescribed by

physicians to reduce appetite or fatigue, and they’re also prescribed as

treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Ritalin is

another stimulant often prescribed in treating ADHD. Cocaine was used for many

years as a local anesthetic for ear, nose, and throat surgery; it’s still used

for some surgical procedures. (Novocaine, a more widely used anesthetic, is a

close chemical cousin of cocaine.) However, all of these stim-ulants are often

abused as recreational drugs. People use these drugs to boost their energy,

mood, and sense of confidence; to decrease the need for sleep; and to improve

athletic performance. These benefits may come at a high cost, though, because

stimulant use can lead to physical and psychological dependence. What’s more, a

regular user who abruptly stops using one of these drugs is likely to

experience powerful withdrawal symptoms including fatigue, irritability,

depression, headaches, and more.

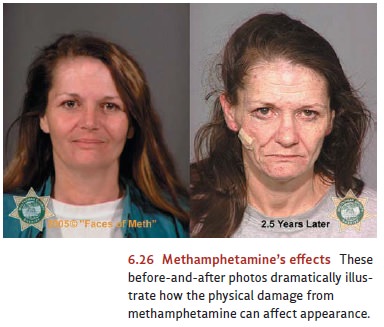

Heavy users of methamphetamine

often end up smoking large quantities of this stimulant. They gain a rush of

energy and pleasure from inhalation and typically feel elated, confident, and

able to stay awake several hours past their usual sleeping time. However, this

aroused state is associated with markedly higher blood pressure that can

increase the user’s risk of heart failure or stroke (Figure 6.26). And,

inevitably, the per-son will reach the end of this aroused period and come

crashing down. At that point, the person is likely to become depressed and

irritable, and sleep for days.

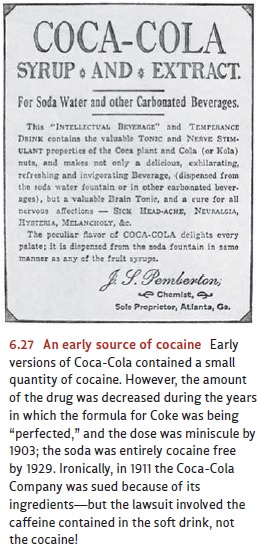

Cocaine is another commonly

used—and abused—stimulant. This drug, derived from the leaves of the coca

plant, is usually snorted or inhaled and quickly enters the

Pp

bloodstream, causing a rush of

excitation and euphoria (Figure 6.27). Once again, though, this rush is only

temporary. The subsequent crash—as with amphetamines—can involve feelings of

fatigue and depression. And here too, long-term abuse can bring with it a set

of problems that include risk of dependence, feelings of paranoia, and an array

of medical difficulties including cardiac arrest and respiratory problems

(Franklin et al., 2002; Gourevitch & Arnsten, 2005).

Another often-abused stimulant is

methylenedioxymetham-phetamine (MDMA; also known as ecstasy). MDMA is a

molecule synthesized in the lab; chemically, it resembles another stimulant—

methamphetamine—as well as the hallucinogen mescaline.

MDMA is a drug often taken in social settings (at clubs or a rave) and produces

an emotional elevation that involves feelings of pleasure, elation, and

warmth. MDMA is also a mild

hallucinogen and produces a strong sense of empathy and closeness to everyone

who is around.

Once again, though, there’s a

price to pay for these benefits. When people are using MDMA, they are likely to

become dehydrated and to clench their jaws so tightly that they can damage

their teeth and jaw muscles. In addition, and like other amphetamines, MDMA

users are susceptible to substantial increases in blood pressure, pulse, and

body temperature. This situation can put the user at greater risk for cardiac

complications (e.g., heart attack) and/or stroke. When the MDMA wears off

(typically, after 3 or 4 hours), the person may also experience a kind of

rebound that makes him feel sluggish and depressed. And at least some research

suggests that continued use of MDMA can create a risk for several other

problems (Biello & Dafters, 2001; Morgan, 2000; Pacifici et al., 2001)—

including impaired memory, problems in one’s body clock that may include sleep

difficul-ties, and weakened immune system function (and so greater

vulnerability to illness).

Overall, it seems clear that

these stimulants do change a person’s conscious experience. Excitement,

euphoria, and increased self-confidence all powerfully color his experiences,

and the stimulants may produce a sense of enhanced awareness that changes how

the world looks, sounds, and feels. The strong sense of empathy produced by

MDMA also adds a pleasurable dimension to one’s experience. But as we’ve seen,

these drugs expose users to serious health risks including life-threatening

medical conditions, a danger of addiction, and a catalog of medical, mental,

and emotional difficulties associated with long-term use.

Related Topics