Chapter: Psychology: Consciousness

Consciousness: Hypnosis

Hypnosis

Everyone has experienced the

altered consciousness associated with sleep. A different form of altered

consciousness is less common, but still deeply interesting. This is the altered

state that a person reaches when hypnotized. Many myths are associated with

hypnosis—including what it is and what it can accomplish. At its essence,

though, hypnosis is a highly relaxed

state in which the participant is extremely suggestible, andthe result is that

he’s likely to feel that his actions and thoughts are happening to him rather

than being produced by him voluntarily. But what’s the exact nature of this state?

WHAT CAN HYPNOSIS ACHIEVE ?

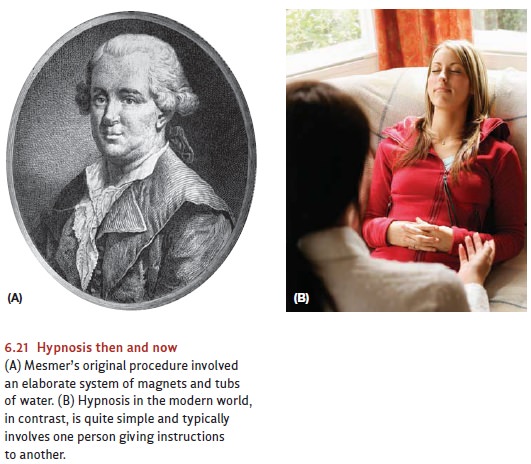

When German physician Franz

Mesmer (1734–1815; Figure 6.21A) first demonstrated his early version of

hypnotism, his technique relied on magnets and tanks of water. Mesmer moved

around his hypnotic subjects while making complex gestures and passing his

hands over their bodies. Most of

these details, however, were just theatrics; modern hyp-nosis procedures are

more straightforward (Figure 6.21B). The person being hypnotized sits quietly

and focuses on some target—a particular sound, or a particular object that is

in view. The hypnotist speaks to the person quietly and monotonously,

encouraging her to relax. The hypnotist also offers various suggestions about

what will happen—including many things that are just inevitable as the person

relaxes: “Your eyelids are drooping downward,” or “Your limbs are getting

heavy.” Gradually, the hypnotist leads the person into a state of deep

relaxation and extreme suggestibility.

Extraordinary claims are

sometimes made about what people can do while in a hypnotized state, but we

need to examine these claims with care. It’s true, for example, that people can

be led to perform unusual and even bizarre actions; but in many cases, these

actions are not the result of the hypnotic state at all. For example, people

under hypnosis can be shown fluid and told that it’s a powerful acid; they’ll

then comply with the cruel instruction to fling the “acid” into another

person’s face. Often, this demonstration is accompanied by the statement that

no sane person would perform this act without hypnosis; so, apparently, we’re

to believe hypnosis can overcome someone’s inhibitions and lead them into

otherwise unspeakable behavior. It turns out, though, that this argument is

mistaken: Exactly the same behavior can be produced by simply asking people to pretend to be hypnotized and to act the

way they think a hypnotized person would (Orne & Evans, 1965). Clearly,

therefore, the hypnosis itself is playing little direct role in producing this

behavior.

We’ll also discuss some of

hypnosis’s alleged effects on memory. For example, in a procedure called hypnotic age regression, the hypnotized

person is instructed that he has returned to an earlier age—and so is now three

years old, for example, or even younger. The hypnotized person will behave

appropriately, talking in a child’s voice and doing childish things. Even so,

the person has not in any real sense “returned” to an earlier age. Instead,

he’s simply acting like an adult believes a child should. We can obtain similar

performances simply by asking people who aren’t hypnotized to simulate a

child’s behavior. In addition, it turns out that adults have a number of

mistaken beliefs about how children behave; under hypnosis, the age-regressed

person acts in a fashion consistent with the (incorrect) adult notions and thus

not like a real child (Silverman & Retzlaff, 1986).

Likewise, many people believe

that hypnosis is a powerful way to retrieve lost memories— for example, they

think that under hypnosis, a witness to an auto collision can recall precise

details of where people were standing at the accident scene, what the cars’

license plate num-bers were, and more—almost as though hypnosis provided a

“rewind” button that allows the person to relive the event and note the details

they had neglected in the original episode. None of this is real, however.

There’s no reason to believe that hypnosis improves memory. Instead, hypnosis

may actually undermine memory—making the person more confident in their

recollection, whether the recollection is correct or not; and making them

markedly more susceptible to leading questions or suggestions that the

hypnotist might offer (e.g., Sheehan, Green, & Truesdale, 1992). This is why

most American, Canadian, and British jurisdictions forbid courtroom testimony

that has been “enhanced” through hypnosis.

At the same time, hypnosis does

have some real and striking effects. For example, people under hypnosis can be

given various instructions for how they should behave after the hypnosis is

done, and in many cases these posthypnotic

instructions are effective. These instructions can, for example, help

people to relax or to eat less (but despite the hype, similar posthypnotic

instructions do little to help people give up cigarettes or other drugs; Nash,

2001). Likewise, a hypnotist can produce posthypnotic

amnesia simply by instructing the hypnotized individual to forget certain

events that happened while the person was in the hypnotized state (Kirsch,

2001). The memory for these events, however, is still in place, even if the

person can’t retrieve it. We know this because the posthypnotic amnesia can be

“lifted” with a subsequent hypnotic instruction that allows the lost memories

to return.

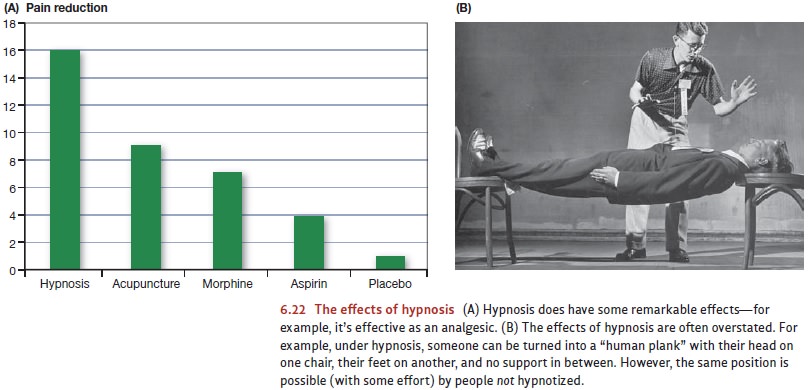

One of the more dramatic effects

of hypnosis, and a powerful indication that hypno-sis can create a special

state of mind, is the phenomenon of hypnotic

analgesia—pain reduction

produced through hypnotic suggestion (Hilgard & Hilgard, 1975; Patterson

Jensen, 2003; Patterson, 2004).

Using this technique, people have undergone various dental procedures and some

forms of surgery without any anesthetic, and they report little suffering. In

some studies, hypnotized people seem to suffer less than people given various

other pain treatments, including acupuncture, aspirin, or even morphine (Stern,

Brown, Ulett, & Sletten, 1977).

It’s important to mention,

though, that not every individual shows the hypnotic analgesia effect, because

some people can’t be hypnotized. In fact, susceptibility to hypnosis varies

broadly. Some people are largely unmoved by a hypnotist’s suggestions, and

other people—“hypnotic virtuosi”—are powerfully influenced. The degree of

susceptibility seems to be linked to how easily the individual can become

absorbed in certain activities, such as watching a movie or playing a video

game—and the people who are more readily “absorbed” are likely to be more

hypnotizable (Barnier & McConkey, 2004; Kirsch & Braffman, 2001;

Tellegen & Atkinson, 1974).

THEORIES O F HYPNOSIS

Does hypnosis truly produce an

altered state of consciousness, so that a hypnotized person is in a

qualitatively different state of mind than someone who’s not hypnotized? More

broadly, what exactly does hypnosis achieve? Some people argue that hypnosis

needs to be understood in relatively mundane social terms—one person (the

hypnotist) simply has an enormous influence on another (the person hypnotized).

Social influences can be incredibly powerful, leading us to perform a range of

actions that we think we would never do. Perhaps hypnosis can be understood in

similar terms—and, if so, then it’s more like our ordinary mode of

consciousness than one might suppose (e.g., Spanos, 1986; Spanos & Coe,

1992).

We’ve already seen some of the

data consistent with this view. For example, hypnotic age regression isn’t a

low-tech time machine; instead, the “regressed” individual is sim-ply playing a

role as well as she can. Likewise, memories called forth under hypnosis are

likely to be constructions—not the result of some highly effective and

specialized

process. Similarly, at least some

of the remarkable feats associated with hypnosis can also be performed without

hypnosis (Figure 6.22), further undermining claims about the special status of

the hypnotic state.

A very different proposal,

however, is that hypnosis involves a special state of dissociation (Hilgard, 1986, 1992), a mental state in which we

shift out of our normal “first-person” per-spective. We might feel like we’re

“outside of ourselves,” watching ourselves from a detached position. We might

also feel like our experiences are happening to someone else and that our

actions are controlled by someone else. Some clinical psychologists suggest

that disso-ciation is a powerful means through which each of us can shield

ourselves from emotion-ally painful experiences. The proposal here, though, is

that similar mechanisms are involved in hypnosis, so that our conscious control

of our thoughts, and our sense of immediate experience, are somehow set aside

for as long as the hypnosis lasts.

As one specific version of this

hypothesis, consciousness researcher Ernest Hilgard has suggested that hypnosis

causes, in effect, a splitting of a person’s awareness into two separate

streams. One stream is responsive to the hypnotist’s instructions, essentially

surrendering control to the hypnotist. The second stream of awareness remains

in the background as a “hidden observer”—so that the person is alert to the

sequence of events—but still leaves the hypnotist in control of what the person

does or, to some extent, feels.

Each of these proposals, one emphasizing social influences and one emphasizing dissociation, may capture important truths. And each proposal may explain different aspects of hypnosis. Indeed, some researchers have proposed this sort of hybrid conception of hypnosis by explaining some aspects of the hypnotic state in terms of social factors and other aspects in terms of dissociation (Kihlstrom & McConkey, 1990; Killeen & Nash, 2003). Perhaps, therefore, we can understand some of hypnosis’s effects as not involving changes in consciousness; but at least some of the effects (e.g., the analgesia) do seem to involve an altered state, so the implication is that hypnosis can actually change someone’s conscious status.

Related Topics