Chapter: Psychology: Consciousness

Neural Basis for Consciousness: The Mind-Body Problem

The Mind-Body

Problem

As we noted, the brain is a

physical object: It has a certain mass (about three pounds), a certain

temperature (a degree or two warmer than the rest of the body), and a certain

volume (a bit less than a half gallon). It occupies a specific position in

space. Our conscious thoughts and experiences, on the other hand, are not

physical objects and have none of these properties. An idea, for example, does

not have mass or a specific tem-perature. A feeling of sadness, joy, or fear

has neither volume nor a location in space.

How, therefore, is it possible

for the brain to give rise to our thoughts? How can a physical entity give rise

to nonphysical thoughts and feelings? Conversely, how can our thoughts and

feelings influence the brain or the

body? Imagine that you want to wave to a friend, and so you do. Your arm, of

course, is a physical object with an iden-tifiable mass. To move your arm,

therefore, you need some physical force. But your ini-tial idea (“I want to

wave to Jacob”) is not a physical thing with a mass or a position in space.

How, therefore, could your (nonphysical) idea produce a (physical) force to

move your arm?

The puzzles in play here all stem

from a quandary that philosophers refer to as the mind-body problem. This term refers to the fact that the mind (and

the ideas,thoughts, and feelings it contains) is an entirely different sort of

entity from the physical body—and yet the two, somehow, seem to influence each

other. How can this be? Roughly 400 years ago, the philosopher René Descartes

(1596–1650) confronted these issues and concluded that the mind and the body

had to be understood as entirely different species of things, separate from

each other. The mind, in his view, was defined by the capacity for thought

(Descartes’ term was res cogitans—“thing

that thinks”); the body, on the other hand, was defined by the fact that it had

certain dimensions in physical space (res

extensa—“extended thing”).

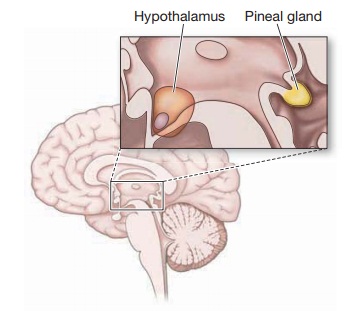

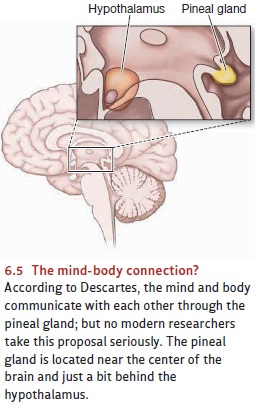

Descartes knew, however, that

mind and body interact: Physical inputs (affecting the body) can cause

experiences (in the mind), and, conversely, thoughts (in the mind) can lead to

action (by the body). To explain these points, Descartes proposed that mind and

body influence each other through the pineal gland, a small structure more or

less at the center of the brain (Figure 6.5). This is the portal, he argued,

through which the physical world communicates sensations to the mind, and the

mind communicates action commands to the body.

Modern scholars uniformly reject

Descartes’ proposed role for the pineal gland, but the mystery that Descartes

laid out remains. Scientists take it for granted that there’s a close linkage

between mind and brain; one often-quoted remark simply asserts that “the mind

is what the brain does”. But, despite this bold assertion, we truly do not know

how the physical events of sensation give rise to conscious experiences or how

conscious decisions give rise to physical move-ments. We can surely talk about

the correspondence between the

physical and mental worlds—what physical events are going on when you

experience “red” or “sad” or “anxious”—but we do not yet have a

cause-and-effect explanation for how these two worlds are linked.

Related Topics