Chapter: Psychology: Consciousness

Consciousness: Brain Damage and Unconscious Functioning

Brain Damage

and Unconscious Functioning

The existence of the cognitive

unconscious sets limits on what we can learn from intro-spection: There’s no

point in asking people to introspect about, say, how their percep-tual

processes operate or how memory retrieval proceeds. These processes, it seems,

take place outside of our awareness and so are invisible to introspection. But,

in addi-tion to this methodological point, the cognitive unconscious raises

questions for us: How much can the cognitive unconscious accomplish? What sorts

of mental operations can go forward without our conscious monitoring or

guidance?

Some of the evidence relevant to

these questions comes from people who have suffered brain damage. We’ll

consider people who suffer from anterograde

amnesia—a profound disruption of their memories—usually caused bydamage in

and around the hippocampus. As we’ll see, these individuals appear almost

normal on tests of implicit memory—memory

that is separate from conscious awareness. In one study, the patients were

first presented with a list of words. Just a few minutes later, they were asked

in one condition to recall these words and were given helpful hints: Was there

a word on the earlier list that began with CL

A__? Even with this cue, the patients failed to remember that the word clasp was on the earlier list—a result

that confirms the diagnosis of amnesia. In another condition, though, the

patients were tested differently. After being presented with the initial list,

they were asked simply to come up with words in response to cues like this:

“Can you think of any word that begins with CL

A__?” We know that other patients who haven’t recently seen the word clasp are likely to respond to this cue

with words more frequently used in conversation (class, clash, clap, clam). However, the patients who had recently

seen clasp did offer this word in

response to the CL A__ cue.

Notice, then, that these patients

have no conscious recollection of the previous list—and so they fail to recall

the list, after just a few minutes, even with helpful hints. At the same time,

the patients do somehow remember the list; we know this because they’re likely

to produce the list words when asked to complete these word stems. These

patients, in other words, show a pattern often referred to as “memory without

awareness”: They’re influenced by a memory that they don’t know they have.

Clearly, therefore, some aspects of remembering—and some influences of

experience—can go smoothly forward even in the absence of a conscious memory.

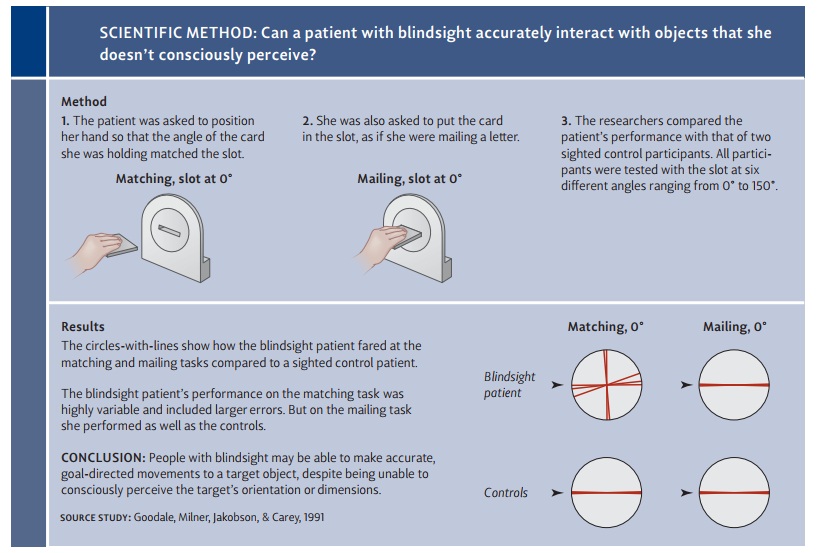

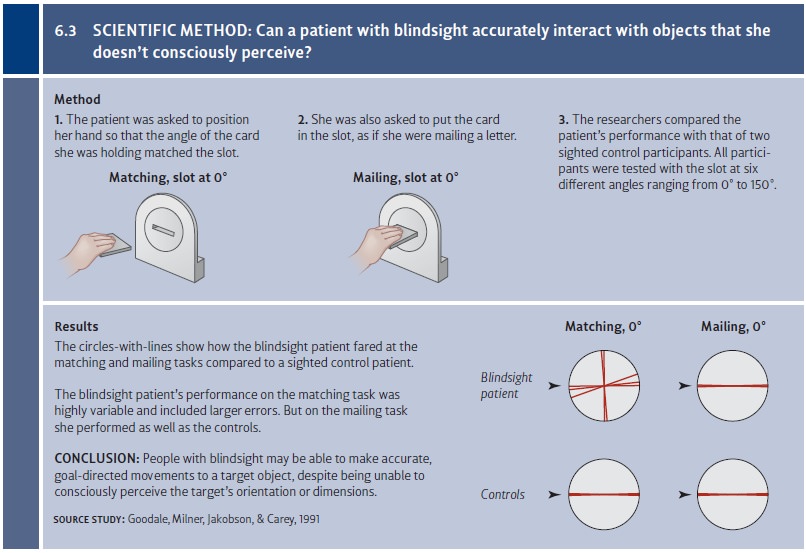

Similar conclusions are suggested

by studies of a remarkable syndrome known as blindsight, which is produced by injuries in the visual cortex.

Patients with this sortof brain damage are, for all practical purposes, blind.

If asked to move around a room, they bump into objects; they do not react to

flashes of bright light; and so on. In one experiment, however, these patients

were asked to hold a card so that its orientation matched a “slot” directly in

front of them. The patients failed in this task, confirming their apparent

blindness. But then the patients were told to put the card into the slot, as if

mailing a letter—and they did this perfectly (Figure 6.3; Rees, Kreiman, &

Koch, 2002; Weiskrantz, 1986, 1997). Thus it seems that these patients can, in

a sense, “see,” but they’re not aware of seeing—again a powerful indicator of

how aspects of

our mental lives can go forward

without conscious experience. (For a related case, see Goodale & Milner,

2004.)

Related Topics