Chapter: Psychology: Consciousness

The Many Brain Areas Needed for Consciousness

The Many Brain

Areas Needed for Consciousness

How do we go about exploring the

correspondence between mind and brain, between the mental world and the

physical one? One way is to examine the brain status of people who have

“diminished” states of consciousness—people who are anesthetized or even in

comas. In each case, we can ask: What is different in the brains of these

individuals that might explain why they’re not conscious?

Research on this topic conveys a

simple message: Many different brain areas seem crucial for consciousness, and

so we can’t expect to locate some group of neurons or some place in the brain

that’s the “consciousness center” and functions as if it’s a light bulb that

lights up when we’re conscious and then changes its brightness when our mental

state changes.

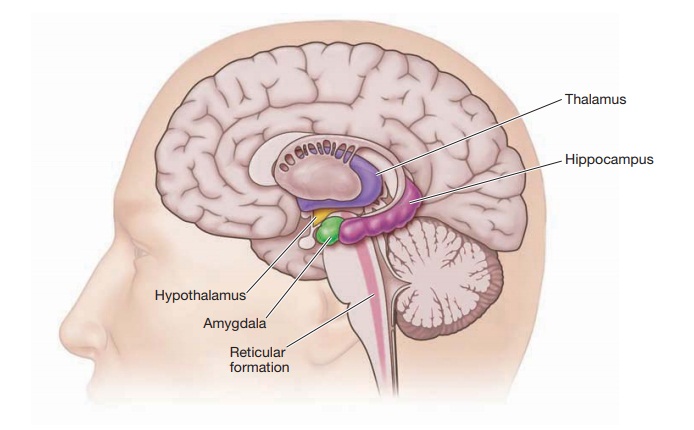

In fact, research in this arena

suggests a distinction between two broad categories of brain sites,

corresponding to two aspects of consciousness (Figure 6.6). First, there is

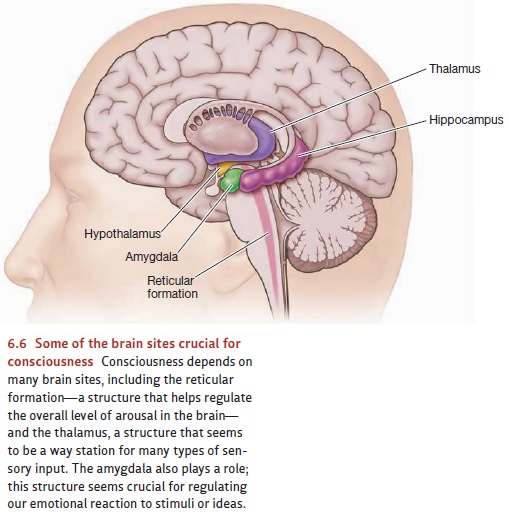

the level of alertness or sensitivity, independent of what the person is alert or sensitive to. We can think of this as the difference between being dimly aware of a stimulus (oran idea, or a memory) and being highly alert and totally focused on that stimulus. This aspect of consciousness is disrupted when someone suffers damage to certain sites in either the thalamus or the reticular activating system in the brain stem—a system that controls the overall arousal level of the forebrain and that also helps control the cycling of sleep and wakefulness (e.g., Koch, 2008).

Second, our

consciousness also varies

in its content.

Sometimes we’re thinking about our

immediate environment; sometimes

we’re thinking about

past events. Sometimes we’re

focused on an immediate task, and sometimes we’re dreaming about the future.

These various contents for consciousness require different brain sites, and so

cortical structures in the visual system are especially active when we’re

consciously aware of sights

in front of

our eyes; cortical structures

in the forebrain

are essential when we’re

thinking about some

stimulus that is

no longer present

in our environment, and so on

(Figure 6.7).

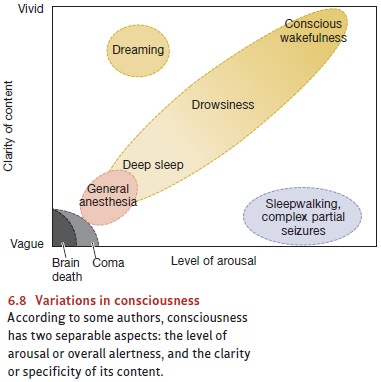

In fact, this broad distinction

between the degree of awareness or sensitivity and the content of

consciousness may be

useful for us

in thinking about

variations in consciousness, as

suggested by Figure 6.8 (after Laureys, 2005; also Koch, 2008). In dreaming,

for example, we are

conscious of a

richly detailed scene, with

its various sights and

sounds and events,

and so there’s

a well-defined content—but

our sensitivity to the

environment is low.

By contrast, in the peculiar state associated with sleepwalking, we’re

sensitive to certain aspects of the

world—so we can, for example, navigate through a complex environment—but we

seem to have no particular thoughts in mind, so the content of our

consciousness is not well defined.

Related Topics