Chapter: Clinical Dermatology: Infections

Viral infections: Herpes zoster

Herpes

zoster

Cause

Shingles

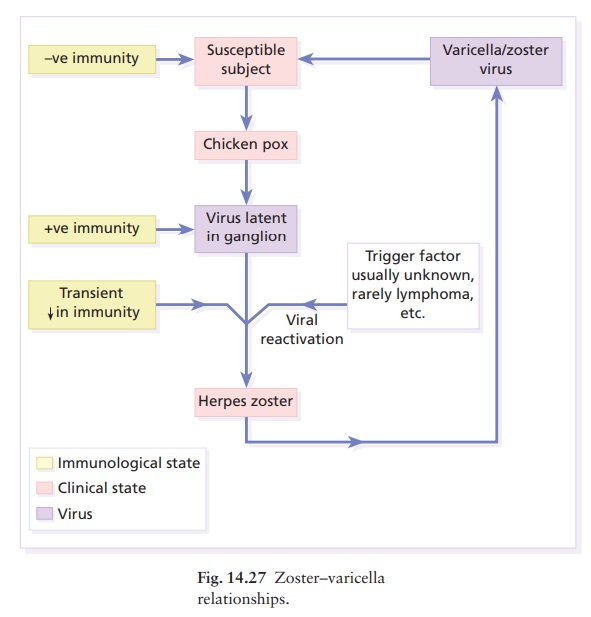

too is caused by the herpes virus varicella-zoster. An attack is a result of

the reactivation, usually for no obvious reason, of virus that has remained

dormant in a sensory root ganglion since an earlier episode of chickenpox

(varicella). The incidence of shingles is highest in old age, and in conditions

such as HodgkinŌĆÖs disease, AIDS and leukaemia, which weaken normal defence

mechanisms. Shingles does not occur in epidemics; its clinical manifestations

are caused by virus acquired in the past. However, patients with zoster can

transmit the virus to others in whom it will cause chickenpox (Fig. 14.27).

Presentation and course

Attacks

usually start with a burning pain, soon followed by erythema and grouped,

sometimes blood-filled, vesicles scattered over a dermatome. The clear vesicles

quickly become purulent, and over the space of a few days burst and crust.

Scabs usually separate in 2ŌĆō3 weeks, sometimes leaving depressed depig-mented

scars.

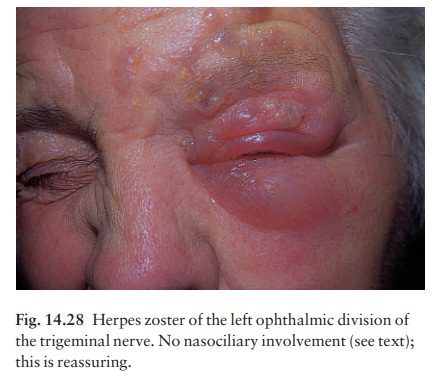

Zoster is characteristically unilateral (Fig. 14.28). It may affect more than one adjacent dermatome. The thoracic segments and the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve are involved disproportionately often.

It

is not uncommon for a few pock-like lesions to be found outside the main

segment of involvement, but a generalized chickenpox-like eruption accompanying

segmental zoster should raise suspicions of an under-lying immunocompromised

state or malignancy, par-ticularly if the lesions are unusually haemorrhagic or

necrotic.

Complications

ŌĆó

Secondary bacterial infection is

common.

ŌĆó

Motor nerve involvement is uncommon,

but has led to paralysis of ocular muscles, the facial muscles, the diaphragm

and the bladder.

ŌĆó

Zoster of the ophthalmic division of

the trige-minal nerve can lead to corneal ulcers and scarring. A good clinical

clue here is involvement of the naso-ciliary branch (vesicles grouped on the

side of the nose).

ŌĆó

Persistent neuralgic pain, after the

acute episode is over, is most common in the elderly.

Differential diagnosis

Occasionally, before the rash has appeared, the initial pain is taken for an emergency such as acute appendicitis or myocardial infarction. Otherwise, the dermatomal distribution, and the pain, allow zoster to be distinguished easily from herpes simplex, eczema and impetigo.

Investigations

Cultures

are of little help as they take 5ŌĆō7 days, and are only positive in 70% of

cases. Biopsy or Tzanck smears show multinucleated giant cells and a ballooning

degeneration of keratinocytes, indicative of a herpes infection. Any clinical

suspicions about underlying conditions, such as HodgkinŌĆÖs disease, chronic

lymphatic leukaemia or AIDS, require further investigation.

Treatment

Systemic

treatment should be given to all patients if diagnosed in the early stages of

the disease. It is essen-tial that this treatment should start within the first

5 days of an attack. Famciclovir and valaciclovir are as effective as

aciclovir; they depend on virus-specific thymidine kinase for their antiviral

activity. All three drugs are safe, and using them may cut down the chance of

getting postherpetic neuralgia, particularly in the elderly.

If

diagnosed late in the course of the disease, systemic treatment is not likely

to be effective and treatment should be supportive with rest, analgesics and

bland applications such as calamine. Secondary bacterial infection should be

treated appropriately.

A

trial of systemic carbamazepine, gabapentin or amitriptyline, or 4 weeks of

topical capsaicin cream, despite the burning sensation it sometimes causes, may

be worthwhile for established post-herpetic neuralgia.

Cause

Herpesvirus

hominis is the cause of herpes simplex. The virus is ubiquitous and carriers

continue to shed virus particles in their saliva or tears. It has been

separated into two types. The lesions caused by type II virus occur mainly on

the genitals, while those of type I are usually extragenital; however, this

distinction is not absolute.

The

route of infection is through mucous mem-branes or abraded skin. After the

episode associated with the primary infection, the virus may become latent,

possibly within nerve ganglia, but still cap-able of giving rise to recurrent

bouts of vesication (recrudescences).

Presentation

Primary infection

The

most common recognizable manifestation of a primary type I infection in

children is an acute gin-givostomatitis accompanied by malaise, headache, fever

and enlarged cervical nodes. Vesicles, soon turn-ing into ulcers, can be seen

scattered over the lips and mucous membranes. The illness lasts about 2 weeks.

Primary

type II virus infections, usually transmitted sexually, cause multiple and

painful genital or peri-anal blisters which rapidly ulcerate.

The

virus can also be inoculated directly into the skin (e.g. during wrestling). A

herpetic whitlow is one example of this direct inoculation. The uncom-fortable

pus-filled blisters on a fingertip are seen most often in medical personnel

attending patients with unsuspected herpes simplex infections.

Recurrent (recrudescent) infections

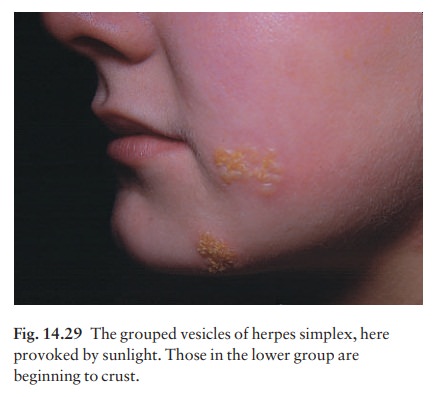

These strike in roughly the same place each time. They may be precipitated by respiratory tract infections (cold sores), ultraviolet radiation, menstruation or even stress. Common sites include the face (Fig. 14.29) and lips (type I), and the genitals (type II), but lesions can occur anywhere. Tingling, burning or even pain is followed within a few hours by the development of erythema and clusters of tense vesicles. Crusting occurs within 24 ŌĆō 48 h and the whole episode lasts about 12 days.

Complications

ŌĆó

Herpes encephalitis or meningitis

can occur with-out any cutaneous clues.

ŌĆó

Disseminated herpes simplex:

widespread vesicles may be part of a severe illness in newborns, debilitated

children or immunosuppressed adults.

ŌĆó

Eczema herpeticum: patients with

atopic eczema are particularly susceptible to widespread cutaneous herpes

simplex infections. Those looking after patients with atopic eczema should stay

away if they have cold sores.

ŌĆó

Herpes simplex can cause recurrent

dendritic ulcers leading to corneal scarring.

ŌĆó

In some patients, recurrent herpes

simplex infections are regularly followed by erythema multiforme.

Investigations

None

are usually needed. Doubts over the diagnosis can be dispelled by culturing the

virus from vesicle fluid. Antibody titres rise with primary, but not with

recurrent infections.

Treatment

ŌĆśOld-fashionedŌĆÖ

remedies suffice for occasional mild recurrent attacks; sun block may cut down

their frequency. Dabbing with surgical spirit is helpful, and secondary

bacterial infection can be reduced by topical bacitracin, mupirocin, framycetin

or fusidic acid. For more severe and frequent attacks, aciclovir cream, if used

at the first sign of the recrudescence, and applied five or six times a day for

the first 4 days of the episode, cuts down the length of attacks and perhaps

increases the intervals between them.

Aciclovir

tablets, 200 mg five times daily for 5 days, is more effective and can be given

to those with widespread or systemic involve-ment. Recurrences in the

immunocompromised can usually be prevented by long-term treatment at a lower

dosage. Famciclovir and valaciclovir are meta-bolized by the body into

aciclovir and are as effective as aciclovir, having the additional advantage of

need-ing fewer doses per day.

Related Topics