Chapter: Clinical Dermatology: Infections

Bacterial infections: The resident flora of the skin

Bacterial infections

The resident flora of the skin

The

surface of the skin teems with micro-organisms, which are most numerous in

moist hairy areas, rich in sebaceous glands. Organisms are found, in clusters,

in irregularities in the stratum corneum and within the hair follicles. The

resident flora is a mixture of harm-less and poorly classified staphylococci,

micrococci and diphtheroids. Staphylococcus epidermidis and

aerobic diphtheroids predominate on the surface, and anaerobic diphtheroids

(proprionibacteria sp.) deep in the hair follicles. Several species of

lipophilic yeasts also exist on the skin. The proportion of the differ-ent

organisms varies from person to person but, once established, an individualŌĆÖs

skin flora tends to remain stable and helps to defend the skin against outside

pathogens by bacterial interference or anti-biotic production. Nevertheless,

overgrowth of skin diphtheroids can itself lead to clinical problems.

Trichomycosis axillaris

This

is a common condition, seen, if looked for, in up to one-quarter of adult

males. The axillary hairs become beaded with concretions, usually yellow, made

up of colonies of commensal diphtheroids. Clothing becomes stained in the

armpits. Topical antibiotic ointments, or shaving, will clear the condition.

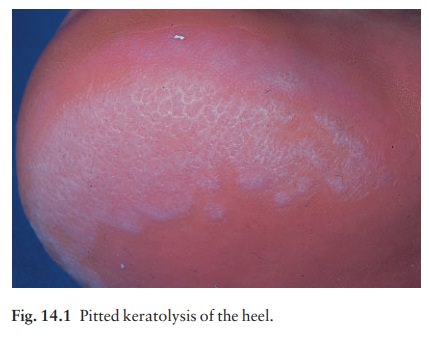

Pitted keratolysis

The

combination of unusually sweaty feet and occlusive shoes encourages the growth

of diphtheroid

The result is a cribriform pattern of fine punched-out

depressions on the plantar surface (Fig. 14.1), coupled with an unpleasant

smell (of methane-thiol). Fusidic acid or mupirocin ointment is usually

effective. Occlusive footwear should be replaced by sandals and cotton socks if

possible.

Erythrasma

Some

diphtheroid members of the skin flora pro-duce porphyrins when grown in a

suitable medium; as a result their colonies fluoresce coral pink under WoodŌĆÖs

light. Overgrowth of these strains is some-times the cause of symptom-free

macular wrinkled slightly scaly pink, brown or macerated white areas, most

often found in the armpits or groins, or between the toes. In diabetics, larger

areas of the trunk may be involved. Diagnosis is helped by the fact that these

areas also fluoresce coral pink with WoodŌĆÖs light. Topical fusidic acid or

miconazole will clear the condition.

Staphylococcal infections

Staphylococcus

aureus is not part of the residentflora of the skin other than in a

minority who carry it in their nostrils, perineum or armpits. Carriage rates

vary with age. Nasal carriage is almost invariable in babies born in hospital,

becomes less frequent during infancy, and rises again during the school years

to the adult level of roughly 30%. Rather fewer carry the organism in the

armpits or groin. Staphylococci can also multiply on areas of diseased skin

such as eczema, often without causing obvious sepsis. A minor breach in the

skinŌĆÖs defences is probably neces-sary for a frank staphylococcal infection to

establish itself; some strains are particularly likely to cause skin sepsis.

Impetigo

Cause

Impetigo

may be caused by staphylococci, strepto-cocci, or by both together. As a useful

rule of thumb, the bullous type is usually caused by Staphylococcusaureus,

whereas the crusted ulcerated type is causedby ╬▓-haemolytic

strains of streptococci. Both are highly contagious.

Presentation A thin-walled flaccid clear blister

forms, and may become pustular before rupturing to leave an extend-ing area of

exudation and yellowish crusting (Fig. 14.2). Lesions are often multiple,

particularly around the face. The lesions may be more obviously bullous in

infants. A follicular type of impetigo (superficial folliculitis) is also

common.

Course

The

condition can spread rapidly through a family or class. It tends to clear slowly

even without treatment.

Complications

Streptococcal impetigo can trigger an acute glomerulonephritis.

Differential diagnosis

Herpes

simplex may become impetiginized, as may eczema. Always think of a possible

underlying cause such as this. Recurrent impetigo of the head and neck, for

example, should prompt a search for scalp lice.

Investigation and treatment

The

diagnosis is usually made on clinical grounds. Swabs should be taken and sent

to the laboratory for culture, but treatment must not be held up until the

results are available. Systemic antibiotics (such as flucloxacillin,

erythromycin or cephalexin (cefalexin)) are needed for severe cases or if a

nephritogenic strain of strepto-coccus is suspected (penicillin V). For minor

cases the removal of crusts and a topical antibiotic such as neo-mycin, fusidic

acid (not available in the USA), mupirocin or bacitracin will suffice.

Ecthyma

This

term describes ulcers forming under a crusted surface infection. The site may

have been that of an insect bite or of neglected minor trauma. The bacterial

pathogens

and their treatment are similar to those of impetigo; however, in contrast to

impetigo, ecthyma heals with scarring.

Furunculosis (boils)

Cause

A

boil is an acute pustular infection of a hair follicle, usually with Staphylococcus

aureus. Adolescent boys are especially susceptible to them.

Presentation and course

A

tender red nodule enlarges, and later may discharge pus and its central ŌĆścoreŌĆÖ

before healing to leave a scar. Fever and enlarged draining nodes complete the

picture. Most patients have one or two boils only, and then clear; a few suffer

from a tiresome sequence of boils (chronic furunculosis).

Complications

Cavernous sinus thrombosis is an unusual complication of boils on the central face. Septicaemia may occur but is rare.

Differential diagnosis

The

diagnosis is straightforward but hidradenitis suppurativa should be considered if only the groin and

axillae are involved.

Investigations in chronic furunculosis

ŌĆó

General examination: look for

underlying skin dis-ease (e.g. scabies, pediculosis, eczema).

ŌĆó Test the urine for sugar. Full blood count.

ŌĆó

Culture swabs from lesions, and

carrier sites (nostrils, perineum) of the patient and immediate family.

ŌĆó

Immunological evaluation only if the

patient has recurrent or unusual internal infections too.

Treatment

Acute

episodes will respond to an appropriate anti-biotic; incision speeds healing.

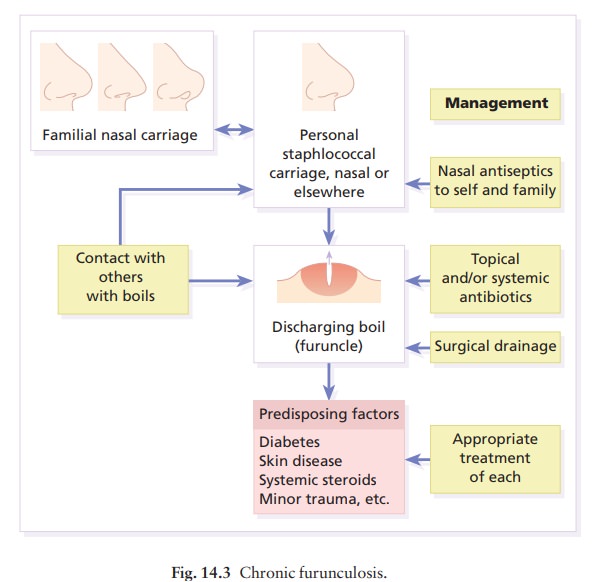

In

chronic furunculosis (Fig. 14.3):

ŌĆó

Treat carrier sites such as the nose

and groin twice daily for 6 weeks with an appropriate topical antiseptic or

antibiotic (e.g. chlorhexidine solution, mupirocin cream or clindamycin solution).

Treat family carriers in the same way.

ŌĆó

Treat lesions with a topical

antibiotic. In stubborn cases add 6 weeks of a systemic antibiotic chosen to

cover organismŌĆÖs proven sensitivities.

ŌĆó Daily bath using an antiseptic soap.

ŌĆó

Improve hygiene and nutritional

state, if faulty.

Carbuncle

A

group of adjacent hair follicles becomes deeply infected with Staphylococcus

aureus, leading to a swollen painful suppurating area discharging

pus from several points. The pain and systemic upset are greater than those of a

boil. Diabetes must be excluded. Treatment needs both topical and systemic

antibiotics. Incision and drainage has been shown to speed up healing, although

it is not always easy when there are multiple deep pus-filled pockets.

Con-sider the possibility of a fungal kerion

in unresponsive carbuncles.

Scalded skin syndrome

In

this condition the skin changes resemble a scald. Erythema and tenderness are

followed by the loosen-ing of large areas of overlying epidermis (Fig. 14.4).

In children

the condition is usually caused by a staphylo-coccal infection elsewhere (e.g.

impetigo or conjunct-ivitis). Organisms in what may be only a minor local

infection release a toxin (exfoliatin) that causes a split to occur high in the

epidermis. With systemic anti-biotics the outlook is good.

This

is in contrast to toxic epidermal necrolysis, which is usually drug-induced.

The damage to the epi-dermis in toxic epidermal necrolysis is full thickness,

and a skin biopsy will distinguish it from the scalded skin syndrome.

Toxic shock syndrome

A

staphylococcal toxin is also responsible for this con-dition, in which fever, a

rashausually a widespread erythemaaand sometimes circulatory collapse are

fol-lowed a week or two later by characteristic desquama-tion, most marked on

the fingers and hands. Many cases have followed staphylococcal overgrowth in

the vagina of women using tampons. Systemic antibiotics and irrigation of the

infected site are needed.

Related Topics