Chapter: Ophthalmology: Retina

Retinal Detachment

Degenerative Retinal Disorders

Retinal Detachment

Definition

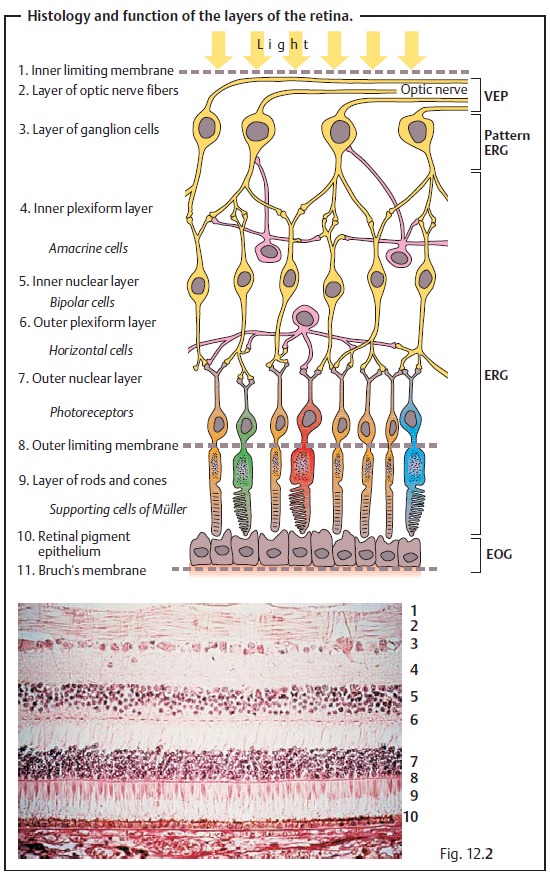

Retinal detachment refers to the separation of

the neurosensory retina (see Fig. 12.2a)

from the underlying retinal pigment epithelium, to which normally it is loosely

attached. This can be classified into four types:

âť– Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment results from a tear, i.e., a break inthe

retina.

âť– Tractional retinal detachment results from traction, i.e., from

vitreousstrands that exert tensile forces on the retina (see proliferative

vitreoreti-nopathy and complicated retinal detachment).

âť– Exudative retinal detachment is caused by fluid. Blood, lipids, or

serousfluid accumulates between the neurosensory retina and the retinal

pig-ment epithelium. Coats’ disease is a typical example.

âť– Tumor-related retinal detachment.

Primary retinal detachment usually results from a tear. In rare cases, second-ary retinal detachment may also result from a tear due to

other disorders orinjuries. Combinations of both are also possible but rare.

Proliferative vitreore-tinopathy frequently develops from a chronic retinal

detachment.

Epidemiology:

Although retinal detachments are relatively rarely encoun-tered

in ophthalmologic practice, they are clinically highly significant as they can

lead to blindness if not treated immediately.

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (most frequent form): Approxi-mately 7% of all adults have

retinal breaks. The incidence of this finding increases with advanced age. The peak incidence is

between the fifth and seventh decades of life. This indicates the significance

of posterior vitreous detachment (separation of the vitreous body from inner

surface of the retina; also age-related) as a cause of retinal detachment. The

annual incidence of retinal detachment is one per 10 000 persons; the

prevalence is about 0.4% in the elderly. There is a known familial disposition,

and retinal detachment also occurs in conjunction with myopia. The prevalence of retinal detachment with emmetropia

(normal vision) is 0.2 % compared with 7% in the presence of severe myopia

exceeding minus 10 diopters.

Exudative, tractional, and tumor-related retinal detachments areencountered far less frequently.

Etiology:

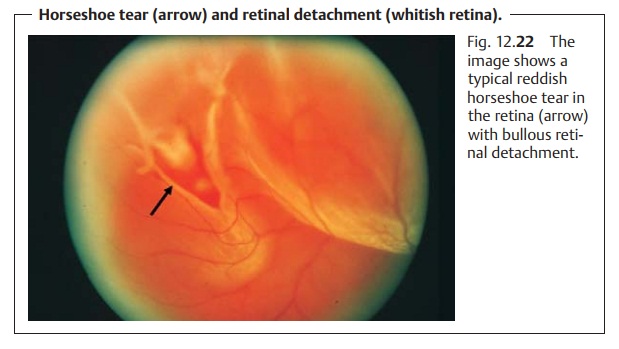

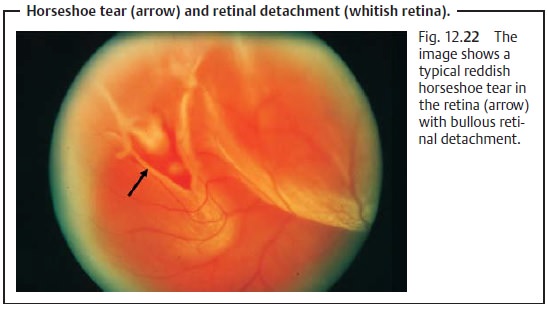

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment.This disorder develops froman existing break in the retina. Usually this break is in the peripheral retina, rarely in the macula (Fig. 12.22). Two types of breaks are distinguished:

âť– Round breaks: A portion of the retina has been completely torn out due to

aposterior vitreous detachment.

âť– Horseshoe tears: The retina is only slightly torn.

Not every retinal break leads to retinal

detachment. This will occur only where the liquified vitreous body separates,

and vitreous humor penetrates beneath the retina through the tear. The retinal

detachment occurs when the forces of adhesion can no longer withstand this

process. Tractional forces (tensile forces) of the vitreous body (usually

vitreous strands) can also cause retinal detachment with or without synchysis.

In this and every other type of retinal detachment, there is a dynamic interplay of tractional and

adhesiveforces. Whether the retina will detach depends on which of these

forces isstronger.

Tractional retinal detachment.This develops from the tensile forces exertedon the retina by

preretinal fibrovascular strands (see proliferative vitreoreti-nopathy)

especially in proliferative retinal diseases such as diabetic reti-nopathy.

Exudative retinal detachment.The primary cause of this type is the break-down of the inner or

outer blood – retina barrier, usually as a result of a vascu-lar disorder such

as Coats’ disease. Subretinal fluid with or without hard exu-date accumulates

between the neurosensory retina and the retinal pigment epithelium.

Tumor-related retinal detachment.Either the transudate from the tumorvasculature or the mass of

the tumor separates the retina from its underlying tissue.

Symptoms:

Retinal detachment can remain asymptomatic for a long time.

Inthe stage of acute posterior vitreous detachment, the patient will notice flashes of light (photopsia) and floaters, black points that move with

thepatient’s gaze. A posterior vitreous detachment that causes a retinal tear

may also cause avulsion of a retinal vessel. Blood from this vessel will then

enter the vitreous body. The patient will perceive this as “black rain,” numerous slowly falling

small black dots. Another symptom is a dark

shadow in thevisual field. This occurs when the retina detaches. The

patient will perceive afalling curtain or a rising wall, depending on whether

the detachment is supe-rior or inferior. A break in the center of the retina

will result in a sudden and significant loss

of visual acuity, which will include metamorphopsia (image distortion) if

the macula is involved.

Diagnostic considerations:

The lesion is diagnosed by stereoscopic exami-nation of the

fundus with the pupil dilated. The detached retina will be white and edematous

and will lose its transparency. Ophthalmoscopy will reveal a bullous retinal

detachment; in rhegmatogenous retinal

detachment, a bright red retinal break will also be visible (see Fig. 12.22). The tears in rheg-matogenous

retinal detachment usually occur in the superior half of the ret-ina in a

region of equatorial degeneration. In tractional

retinal detachment, the bullous detachment will be accompanied by

preretinal gray strands. In exudative

retinal detachment, one will observe the typical picture of

serousdetachment; the exudative retinal detachment will generally be

accom-panied by massive fatty deposits and often by intraretinal bleeding.

The tumor-related retinal

detachment (as can occur with

a malignant melanoma) either leads to secondary retinal detachment over the

tumor or at some distance from the tumor in the inferior peripheral retina.

Ultrasound studies can help confirm the diagnosis where retinal findings are

equivocal or a tumor is suspected.

An inferior retinal detachment at some

distance from the tumor is a sign that the tumor is malignant.

Differential diagnosis:

Degenerativeretinoschisisis

the primary disorderthat should be excluded as it can also involve rhegmatogenous

retinal detach-ments in rare cases. A retinal detachment may also be confused

with a choroidal detachment. Fluid accumulation in the choroid, due to

inflam-matory choroidal disorders such as Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, causes

the retinal pigment epithelium and neurosensory retina to bulge outward. These

forms of retinal detachment have a greenish dark brown color in con-trast to

the other forms of retinal detachment discussed here.

Treatment:

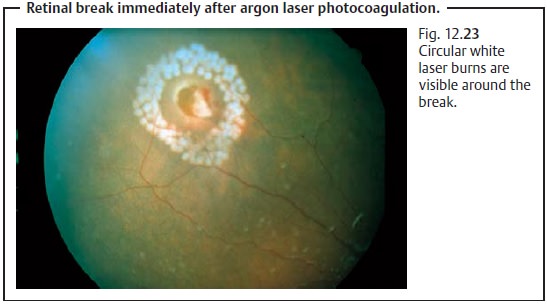

Retinal breaks with minimal circular retinal detachment can betreated with argon laser coagulation (Fig. 12.23). The retina surrounding the break is fused to the underlying tissue whereas the break itself is left open. The scars resulting from argon laser therapy are sufficient to prevent any further retinal detachment.

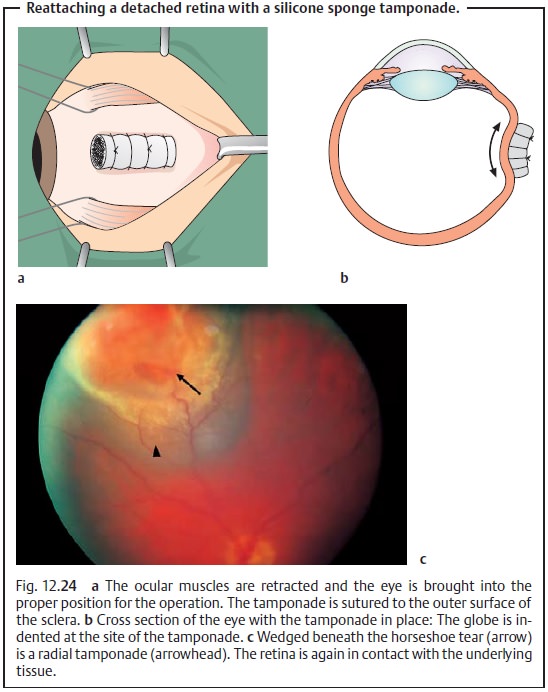

More extensive

retinal detachments are usually treated with a retinal tamponade with an

elastic silicone sponge that is sutured to the outer surface of the sclera, a so-called

budding procedure (Fig. 12.24a – c). It can be sutured either in a radial position (perpendicular

to the limbus) or parallel to the limbus. This indents the wall of the globe at

the retinal break and brings the portion of the retina in which the break is

located back into contact with the retinal pigment epithelium. The indentation

also reduces the traction of the vitreous body on the retina. An artifical scar is created to stabilize the restored contact between the

neurosensory retina and retinal pigment epithelium. This is achieved with a

cryoprobe. After a successful operation, this scar prevents recurring retinal

detachment. Where there are several retinal breaks or the break cannot be

located, a silicone cer-clage is applied to the globe as a circumferential buckling procedure.

The pro-cedures described up until now apply to uncomplicated retinal detachments, i.e., without proliferative

vitreoretinopathy. Suturing a retinal tamponade with silicone sponge may also

be attempted initially in a complicated

retinaldetachment with proliferative vitreoretinopathy. If this treatment

isunsuccessful, the vitreoretinal proliferations are excised, and a vitrectomy isperformed in which the

vitreous body is replaced with Ringer’s solution, gas,or silicone oil. These

fluids tamponade the eye from within.

Prophylaxis:

High-risk patients above the age of 40 with a positive

familyhistory and severe myopia should be regularly examined by an

ophthalmolo-gist, preferably once a year.

Clinical course and prognosis:

About 95% of rhegmatogenous retinaldetachments can be treated successfully with surgery. Where there has been macular involvement (i.e., the initial detachment included the macula), a loss of visual acuity will remain. The prognosis for the other forms of retinaldetachment is usually poor, and they are often associated with significantloss of visual acuity.

Related Topics