Chapter: Civil : Structural dynamics of earthquake engineering

Response of structures to periodic dynamic loadings

Response

of structures to periodic dynamic loadings

Abstract: In many real problems, it is

found that exciting forces vary with time in a non-harmonic fashion that

may be periodic or non-periodic. When the function defined over a period

repeats indefinitely, it is known as a periodic function. In this page, we

apply the Fourier series to determine the response of the system to periodic

forces.

Key words: periodic function, Fourier

series, odd function, even function, frequency domain, spectrum, Gibbs

phenomenon.

Introduction

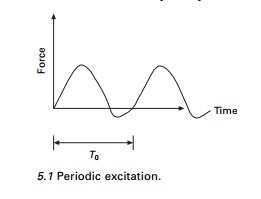

We have seen in Chapter 4 that

harmonic excitation occurs in power installations equipped with rotating and

reciprocating machinery. The solution to harmonic excitation is simple and

straightforward since a closed form solution is always available. In many

realistic situations, the exciting forces vary with time in a non-harmonic

fashion that may be periodic or non-periodic. A periodic function is one in

which the portion defined over a period T0 repeats itself

indefinitely, (see Fig. 5.1). Propeller force on a ship, wind loading induced

by vortex shedding on tall slender structures are the examples of periodic

forces, whereas, earthquake ground motion has no resemblance to periodic

function.

This chapter presents the application of Fourier series to

determine the response of a system to periodic forces in the frequency domain,

an alternative approach to the usual analysis of time domain. To make practical

use of Fourier method, it is necessary to replace the integration with finite

sums.

Fourier analysis

Consider an undamped

single-degree-of-freedom (SDOF) system subjected to force F(t)

The governing equation is written as

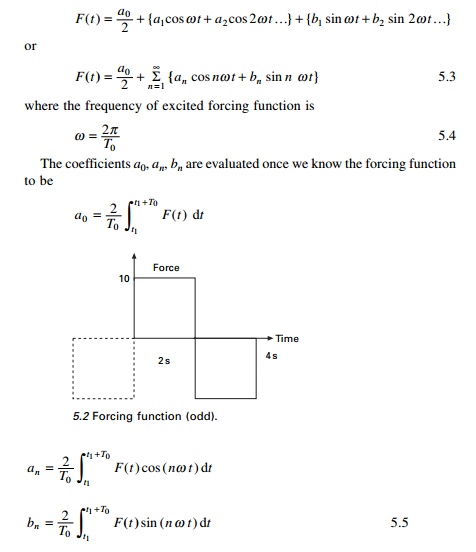

Let the forcing function be

represented as shown in Fig. 5.2. The duration of one pulse or period T0

= 4s.

F(t)

= 10 t <2 s

F(t)

= Ð10 2 < t < 4 5.2

Fourier has shown that a periodic function can be expressed as

a sum of infinite number of sine and cosine terms and such a sum is known as a

Fourier series.

t1 in Eq.

5.5 can take any value of time, but is usually Ð T/2 or zero. Note that

Fourier coefficients a1, an, bn

may be expedited if the forcing function can be recognized as being odd or

even. If the forcing function is anti-symmetric about the origin (y-axis)

then it is an odd function. For example, the given function shown in Fig. 5.2

is an odd function because

For an odd function, the Fourier coefficients a0,

a1,├ē, an = 0

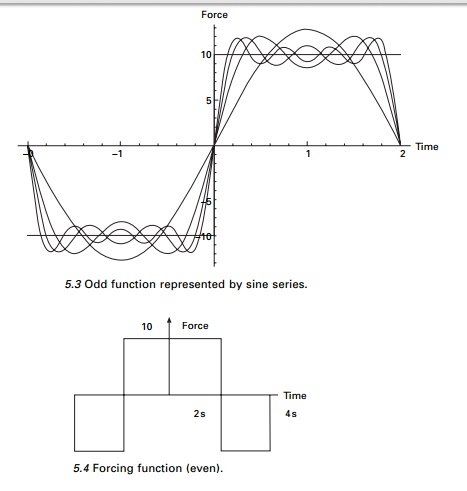

The forcing function is even if

For an even function, the Fourier coefficients b0,

b1,├ē, bn = 0

Clearly then an odd function can

be represented by the Fourier sine series and an even function by the Fourier

cosine series. If, however, the function is neither odd nor even, then the full

Fourier series must be employed. The Fourier coefficients can very easily be

evaluated using the MATHEMATICA package as shown by the following examples.

Example 5.1

Determine the Fourier series

expression for the square wave, periodic function as shown in Fig. 5.2. Plot

the Fourier representation for the first four non-zero harmonic components.

(Assume F0 = 10)

Solution

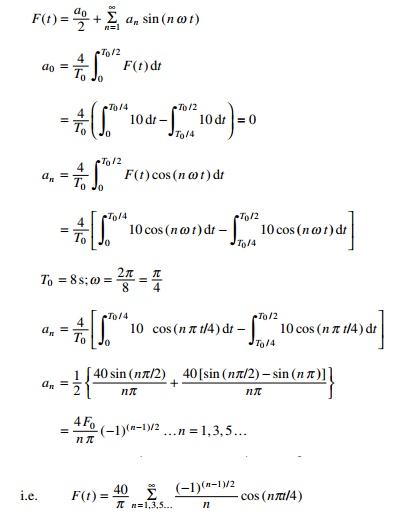

Since the forcing function is an odd function, the Fourier

coefficients a0, a1,├ē, an =

0. Thus the forcing function is represented by the Fourier sine series

as

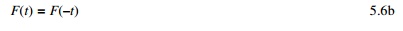

The forcing function is

represented in Fig. 5.3 in terms of 1, 2, 3 and 4 non-zero terms of Fourier

series.

Example 5.2

Determine the Fourier series expression for square wave

periodic forcing function as shown in Fig. 5.4. Plot the Fourier representation

of the first four non-zero components.

Solution

Since F(t) is an even function, b1,

b2, bn are zero. Thus ├'a├Ģ

coefficients are represented by Fourier cosine series as

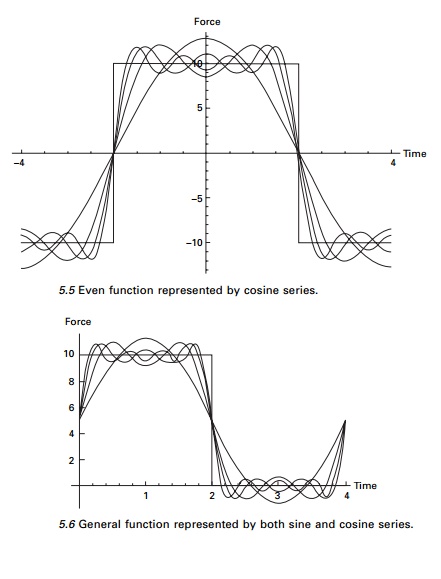

In Fig. 5.5 the forcing function

is represented in terms of 1, 2, 3, 4 non-zero terms of cosine series.

The

MATHEMATICA program is used to find the Fourier coefficients.

Example 5.3

Determine the Fourier series expansion for a square wave

periodic forcing function as shown in Fig. 5.6. Plot the Fourier representation

of the first four non-zero components

Solution

Since F(t) is

neither odd nor even function, this should contain both sine and cosine terms.

In Fig. 5.6 the forcing function is represented in terms of 1, 2, 3 and 4

non-zero terms of Fourier series.

Response to periodic

excitation

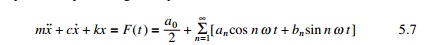

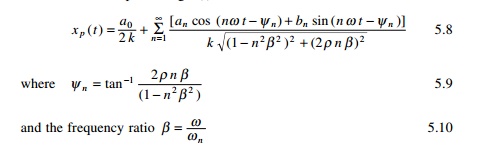

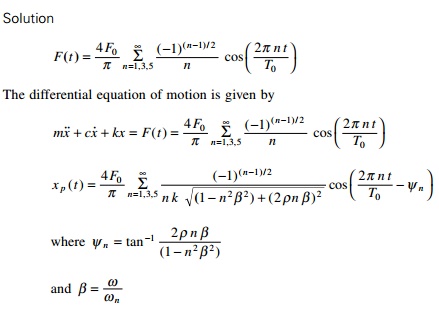

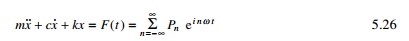

Next, consider the response of a viscously damped SDOF system

to periodic non-harmonic excitation of period T0. The

differential equation of motion of steady state response is given by

in which Fourier series expansion was used to represent F(t).

The transient response will decay with time and is hence neglected. To obtain

the particular solution for the steady state response, it is noted that

differential equation is linear, and therefore principle of superposition is

applicable. Hence the steady state response is merely the sum of the individual

particular solutions for all harmonic terms representing F(t).

Hence we obtain

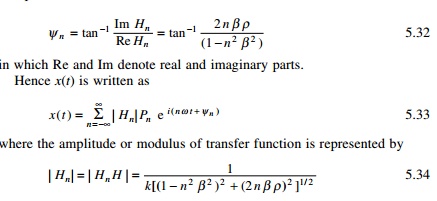

in which Žłn is the

phase angle for the steady state response.

Example 5.4

For the harmonic periodic forcing function shown in Fig. 5.5

determine the steady state response for a viscously under-damped SDOF system.

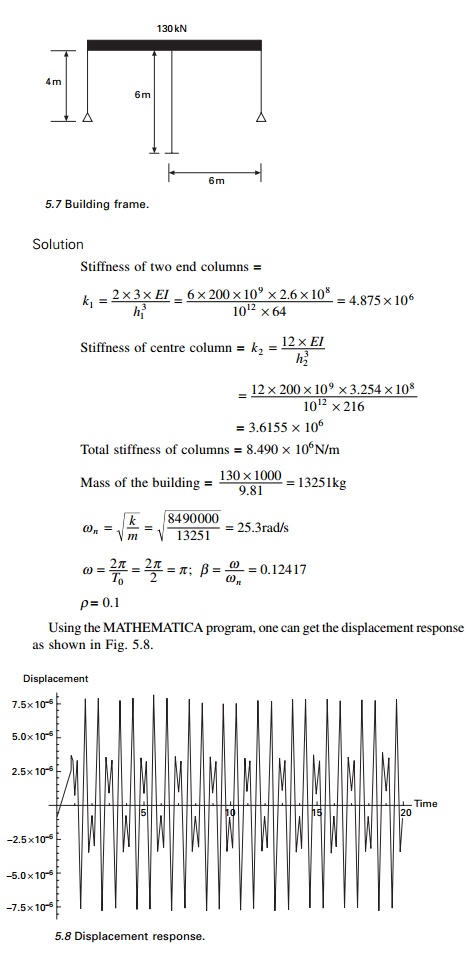

Example 5.5

The building frame shown in Fig. 5.7 is constructed of rigid

girders and flexible columns. The frame supports a uniformly distributed load

of weight of 130kN and is subjected at its girder level to the periodic force

described in Fig. 5.4. Evaluate the steady state response of the structure and

plot displacement vs. time assuming F0 = 80kN, period of

exciting force is 2 s, E = 200GPa, damping factor = 0.1, height of end

columns is 4m, the height of centre column is 6m and the span of the beams is

6m. The values of I for end columns and centre column are 2.6 ├- 108 and 3.254 ├- 108mm4

respectively.

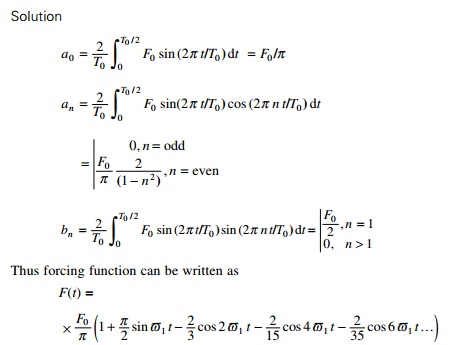

Example 5.6

Consider a system loaded as shown in Fig. 5.9. Find the steady

state response.

in which Ž- = 2ŽĆ/T0.

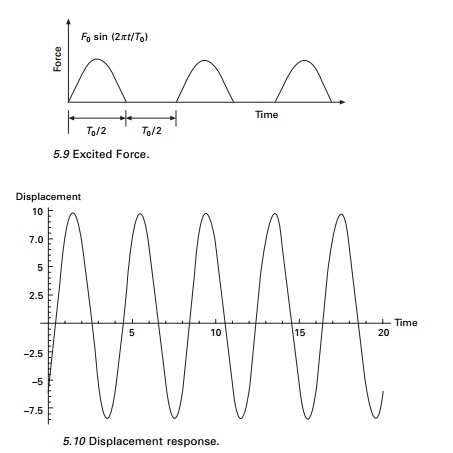

Using the MATHEMATICA program, the displacement response is

obtained for ╬▓ = ŽĆ/4, T0 = 4s Žü = 0.25 as shown in Fig. 5.10.

Frequency domain analysis

The dynamic response of the complex systems can be examined by

two approaches: time domain solution and the frequency domain solution. Up to

now, all solutions have been in time domain and the equations are solved by

integrating with time. In

frequency domain technique, the amplitude coefficients in the Fourier series

solution corresponding to each frequency are determined. For this we use

discrete Fourier transform (DFT) or fast Fourier transform (FFT) methods.

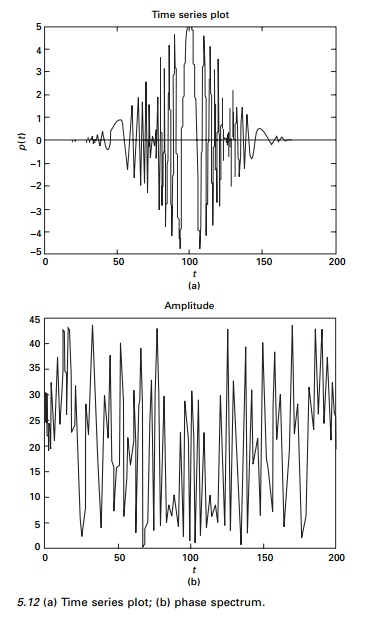

Alternative form of

Fourier series

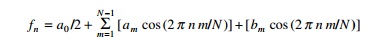

The arbitrary periodic forcing function can be represented in

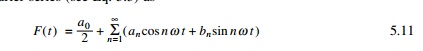

the form of Fourier series (see Eq. 5.3) as

in which a0, a1├ē

an, b1, b2, ├ē bn

are real constants, t is the time and Žē is the forcing frequency given by Žē = 2ŽĆ/T0 where T0

is the period of the forcing function. If the period of the forcing function is

not known or if the forcing function does not have period for this case Žē = 2ŽĆ/TD where TD

is the total time duration of the forcing function.

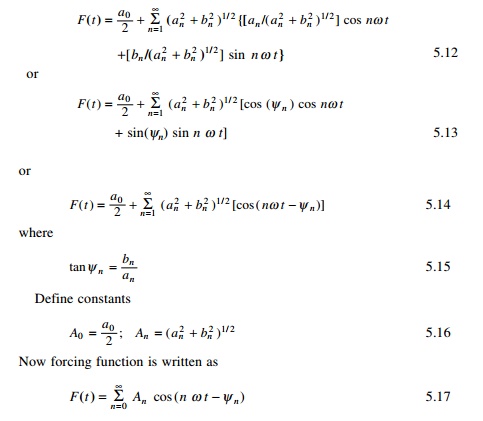

Equation 5.11 may also be written as

in which Žł0 = 0.

Hence forcing function is now written in terms of positive real amplitude and

phase shift. This method replaces the coefficients of an, bn

by An, Žłn. There is still the same number

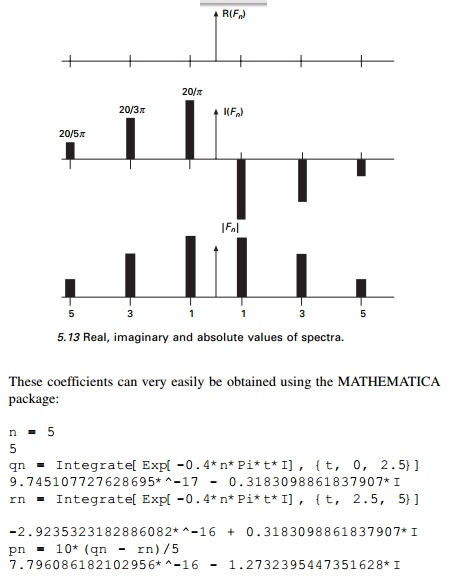

of coefficients. The plots of An and Žłn are

called amplitude spectrum and phase spectrum respectively. They are discrete

and occur at Fourier frequencies nŽē = (2ŽĆ n)/TD.

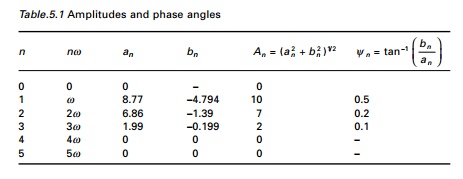

Example 5.7

A periodic load function of three frequency components is

given by

F(t) = 10 cos (Žē t - 0.5) +

7 cos (2Žē t - 0.2) +

2 cos (3 Žē t - 0.1)

in which Žē = 2ŽĆ/TD and TD

= 5s. Plot the periodic function and the amplitude and phase spectrum.

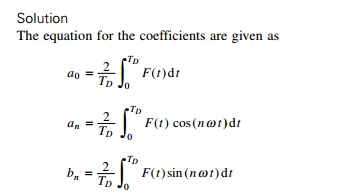

Solution

The equation for the coefficients are given as

except that we use TD as fundamental period.

Evaluating the integrals in the above equations yields the values given in

Table 5.1.

Program 5.3: MATLAB

program to evaluate amplitudes and phase angles

clc; close all;

for i=1:200 t(i)=(i-1)/40;

p(i)=10*cos(2*pi*t(i)/5Ð0.5)+7.0*cos(4*pi*t(i)/5Ð0.2)+2.0*cos(6.0*pi*t(i)/

5Ð0.1) end figure(1) plot(t,p)

xlabel(' t');

ylabel('p(t)');

title(' time series plot');

figure(2)

a=fft(p);

plot(abs(a)); title(' amplitude')

for i=1:200

b(i)=real(a(i));

c(i)=imag(a(i)); d(i)=atan(-c(i)/b(i));

e(i)=sqrt(b(i)^2+c(i)^2);

end

print{' real part',\n); b

print(' imaginary part',\n); c

print(' phase angle',\n); d

print(' amplitude',\n)' e

figure(3)

plot(d); title(' phase')

figure(4);

plot(t,b,t,c,'*');

title(' real and imaginary part(*)')

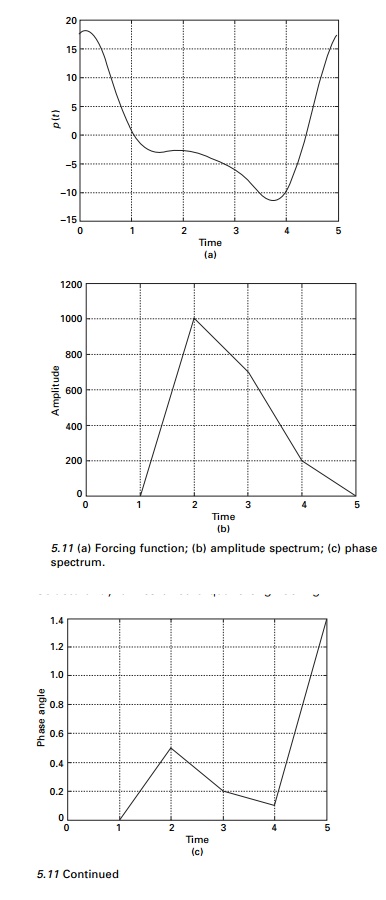

The forcing function F(t) examined in Example

5.6 is rather a simple function, although, from the plot presented in Fig.

5.11a it is not readily

apparent that this is a simple

function. However the amplitude and phase spectrum parts shown in Fig. 5.11b

and 5.11c reveal clearly three cosines and their phases. As functions become

more complex with many frequency components, plots of amplitude spectra become

even more important in understanding the structure of the functions.

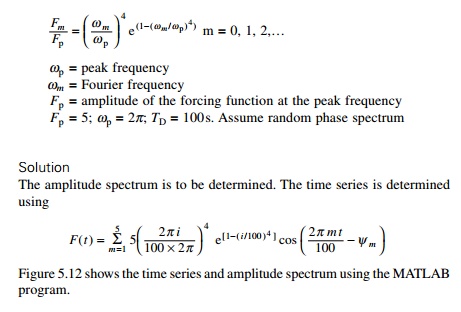

Example 5.8

A simple periodic load is characterized by the following

deterministic amplitude coefficients

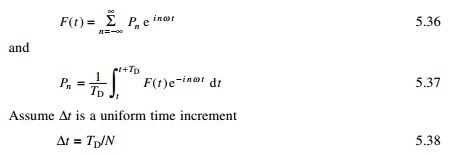

Expression of forcing

function using complex variable approach

The forcing function is written as

The exponential form is more convenient to use than the real

form. To illustrate the fact, consider SDOF system subjected to harmonic

forcing. The equation of motion is given by

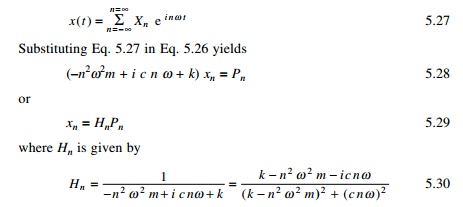

The steady state solution of Eq. 5.26 will respond to same

frequencies making up the forcing function.

Writing in this way, the response at each frequency is simply

a function of the forcing transfer function. For a given structure H

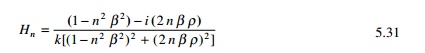

depends only on frequency nŽē. This is termed the frequency domain solution. Consider ╬▓ as the

frequency ratio and Žü as the

damping factor. The function Hn is written as

The phase is now defined as

where Hn* is the complex

conjugate of Pn and Žån is the phase. It is to be noted

that forcing function Pn can be complex. Expressing Pn

as a modulus and phase we get

Since the spectral coefficients are even, this implies that a

spectrum plot we can consider either all frequencies between ├ÉŌł× and Ōł×

or just frequencies from 0 to Ōł× and

double the heights. The former is called a double-sided spectrum and the latter

is called a single-sided spectrum. Both spectra are reasonable representations

and both are used in practice.

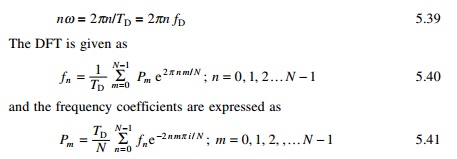

Discrete Fourier

transform (DFT) and fast Fourier transform (FFT)

Although Fourier integral

technique discussed in previous sections provide a means for determining the

transient response of a system, numerical integral of the Fourier integral

became a practical reality only with the publication of Cooley-Tukey algorithm

for the FFT in 1965. Since that date, FFT has revolutionized many areas of

technology such as the areas of measurements and instrumentation.

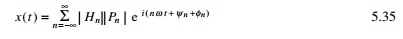

Two steps are involved in the numerical evaluation of Fourier

transforms. DFTs correspond to the equation

where N is the number of points in the time series

approximation of F(t). We can write

The total number of discrete time values and

frequency values are same. The N term appearing before the summation in

Eq. 5.40 is not unique. In

Root o

DFT it can be used as 1/N in Eqs. 5.40 and 5.41 or N

Root in both.

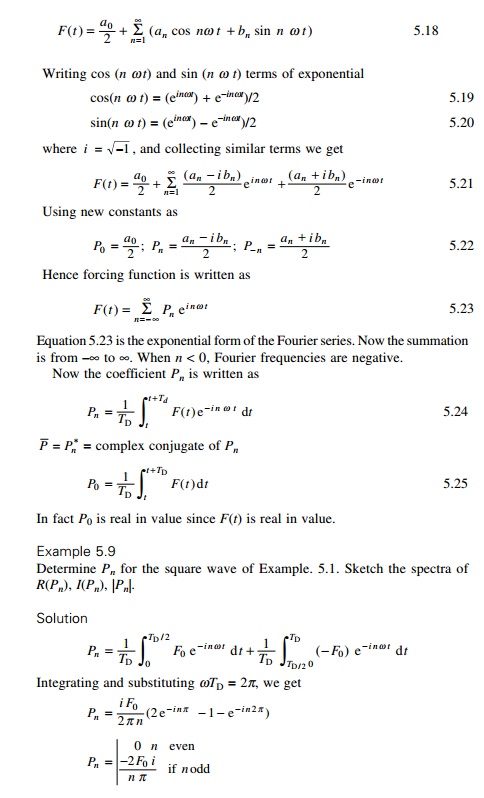

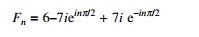

Example 5.10

Determine the DFT of the following function defined by

f (n Ōłåt) = 6 +

14 sin (nŽĆ/2) ├ē

n = 0, 1, 2,├ē, 7

Solution

In this example N = 8 and all coefficients are zero

except a0 = 12; b2 = 14. For this problem

the solution could be determined by inspection. With use of the Euler formulae,

the time series is written as

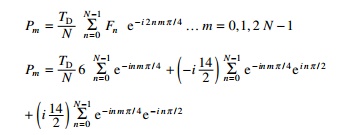

The transform of the series is given by

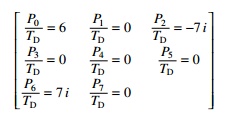

These coefficients may be evaluated using the MATHEMATICA package

and given by

These are the same coefficients

that were determined by inspection of equation defining Pn, Pm

= Pm+n or PÐ2 = P6.

Gibbs phenomenon

The Fourier series approximation of a square wave has been

plotted in Fig. 5.34. The approximation is generally quite good as shown in the

figure. However, an inaccuracy exists at the corners of the wave. Sines and

cosines are smooth, continuous functions and therefore are best suited to

approximately other smooth and continuous functions. However, jumps or

discontinuities exist in them and the approximation is poor. For the square

wave a discontinuity exists at t/T0 = 0.5. At this

location, the square wave has two values +1 and Ð1. When the function has jumps

or double values, a Fourier series passes through the mean of the two points as

shown in Fig. 5.34, which in our case is zero. It is also to be noted that t/T0

= 0.5 the square wave is vertical. The fourier series tends to overshoot at the

corners. This is called the Gibbs phenomenon. This does not

disappear even if large number of terms are used

in the series. It is concluded that the Gibbs phenomenon is

local and the contribution to total energy is minimal.

Summary

Fourier integrals can be evaluated numerically. There are a

number of software packages available to do this, such as MATHEMATICA and

MATLAB. DFT has a finite number of frequencies and Fourier integrals have

continuous frequencies in the interval ├ÉŌł×

< f < Ōł× and high

frequency terms are lost. The other way of doing the Fourier integral is to use

polynomial interpolation functions which can be integrated analytically over

most of the data.

Related Topics