Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Intestinal and Rectal Disorders

Constipation - Abnormalities of Fecal Elimination

Abnormalities of Fecal Elimination

Changes

in patterns of fecal elimination are symptoms of func-tional disorders or

disease of the GI tract. The most common changes seen are constipation,

diarrhea, and fecal incontinence. The nurse should be aware of the possible

causes and thera-peutic management of these problems and of nursing manage-ment

techniques. Education is important for patients with these abnormalities.

CONSTIPATION

Constipation is a term used to describe an abnormal

infrequencyor irregularity of defecation, abnormal hardening of stools that

makes their passage difficult and sometimes painful, a decrease in stool

volume, or retention of stool in the rectum for a prolonged period. Any

variation from normal habits may be considered a problem.

Constipation

can be caused by certain medications (ie, tran-quilizers, anticholinergics,

antidepressants, antihypertensives, opioids, antacids with aluminum, and iron);

rectal or anal disor-ders (eg, hemorrhoids, fissures); obstruction (eg, cancer

of the bowel); metabolic, neurologic, and neuromuscular conditions (eg,

diabetes mellitus, Hirschsprung’s disease, Parkinson’s dis-ease, multiple

sclerosis); endocrine disorders (eg, hypothy-roidism, pheochromocytoma); lead

poisoning; and connective tissue disorders (eg, scleroderma, lupus

erythematosus). Consti-pation is a major problem for patients taking opioids

for chronic pain. Diseases of the colon commonly associated with constipation

are irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and diverticular disease. Constipation can

also occur with an acute disease process in the abdomen (eg, appendicitis).

Other

causes include weakness, immobility, debility, fatigue, and an inability to

increase intra-abdominal pressure to facilitate the passage of stools, as

occurs with emphysema. Many people de-velop constipation because they do not

take the time to defecate or they ignore the urge to defecate. In the United

States, consti-pation is also a result of dietary habits (ie, low consumption

of fiber and inadequate fluid intake), lack of regular exercise, and a

stress-filled life.

Perceived

constipation can also be a problem. This subjective problem occurs when an

individual’s bowel elimination pattern is not consistent with what he or she

perceives as normal. Chronic laxative use is attributed to this problem and is

a major health concern in the United States, especially among the elderly

population.

Pathophysiology

The

pathophysiology of constipation is poorly understood, but it is thought to

include interference with one of three major func-tions of the colon: mucosal

transport (ie, mucosal secretions fa-cilitate the movement of colon contents),

myoelectric activity (ie, mixing of the rectal mass and propulsive actions), or

the processes of defecation. Any of the causative factors previously identified

can interfere with any of these three processes.

The

urge to defecate is stimulated normally by rectal disten-tion, which initiates

a series of four actions: stimulation of the in-hibitory rectoanal reflex,

relaxation of the internal sphincter muscle, relaxation of the external

sphincter muscle and muscles in the pelvic region, and increased

intra-abdominal pressure. Interference with any of these processes can lead to

constipation.If all organic causes are eliminated, idiopathic constipation is

diagnosed.

If the

urge to defecate is ignored, the rectal mucous membrane and musculature become

insensitive to the presence of fecal masses, and consequently, a stronger

stimulus is required to produce the necessary peristaltic rush for defecation.

The ini-tial effect of fecal retention is to produce irritability of the colon,

which at this stage frequently goes into spasm, especially after meals, giving

rise to colicky midabdominal or low abdominal pains. After several years of

this process, the colon loses muscular tone and becomes essentially

unresponsive to normal stimuli. Atony or decreased muscle tone occurs with

aging. This also leads to constipation because the stool is retained for longer

periods.

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical

manifestations include abdominal distention, borborygmus (ie, gurgling or

rumbling sound caused by passage of gas through the intestine), pain and

pressure, decreased appetite, headache, fa-tigue, indigestion, a sensation of

incomplete emptying, straining at stool, and the elimination of small-volume,

hard, dry stools.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Chronic

constipation is usually considered idiopathic, but sec-ondary causes should be

excluded. In patients with severe, in-tractable constipation, further

diagnostic testing is needed (Wong, 1999). The diagnosis of constipation is

based on results of the pa-tient’s history, physical examination, possibly a

barium enema or sigmoidoscopy, and stool testing for occult blood. These tests

are completed to determine whether this symptom results from spasm or narrowing

of the bowel. Anorectal manometry (ie, pressure studies) may be performed to

determine malfunction of the mus-cle and sphincter. Defecography and bowel

transit studies can also assist in the diagnosis.

Complications

Complications of constipation include

hypertension, fecal im-paction, hemorrhoids and fissures, and megacolon.

Increased arte-rial pressure can occur with defecation. Straining at stool,

which results in the Valsalva maneuver (ie, forcibly exhaling with the glot-tis

closed), has a striking effect on arterial blood pressure. During active

straining, the flow of venous blood in the chest is temporar-ily impeded

because of increased intrathoracic pressure. This pres-sure tends to collapse

the large veins in the chest. The atria and the ventricles receive less blood,

and consequently less is delivered by the systolic contractions of the left

ventricle. The cardiac output is decreased, and there is a transient drop in

arterial pressure. Almost immediately after this period of hypotension, a rise

in arterial pres-sure occurs; the pressure is elevated momentarily to a point

far ex-ceeding the original level (ie, rebound phenomenon). In patients with

hypertension, this compensatory reaction may be exaggerated greatly, and the

peaks of pressure attained may be dangerously high—sufficient to rupture a

major artery in the brain or elsewhere.

Fecal

impaction occurs when an accumulated mass of dry feces cannot be expelled. The

mass may be palpable on digital examina-tion, may produce pressure on the

colonic mucosa that results in ulcer formation, and frequently may cause

seepage of liquid stools.

Hemorrhoids

and anal fissures can develop as a result of con-stipation. Hemorrhoids develop as a result of

perianal vascular congestion caused by straining. Anal fissures may result from

the passage of the hard stool through the anus, tearing the lining of the anal

canal.

Megacolon

is a dilated and atonic colon caused by a fecal mass that obstructs the passage

of colon contents. Symptoms include constipation, liquid fecal incontinence,

and abdominal disten-tion. Megacolon can lead to perforation of the bowel.

Gerontologic Considerations

Physician

visits for constipation are more frequent by individuals 65 years of age or

older (Yamada et al., 1999). Elderly people re-port problems with constipation

five times more frequently than younger people. A number of factors contribute

to this increased frequency. People who have loose-fitting dentures or have

lost their teeth have difficulty chewing and frequently choose soft, processed

foods that are low in fiber. Convenience foods, also low in fiber, are widely

used by those who have lost interest in eating. Some older people reduce their

fluid intake if they are not eating regular meals. Lack of exercise and

prolonged bed rest also con-tribute to constipation by decreasing abdominal

muscle tone and intestinal motility as well as anal sphincter tone. Nerve

impulses are dulled, and there is decreased sensation to defecate. Many older

people who overuse laxatives in an attempt to have a daily bowel movement become

dependent on them.

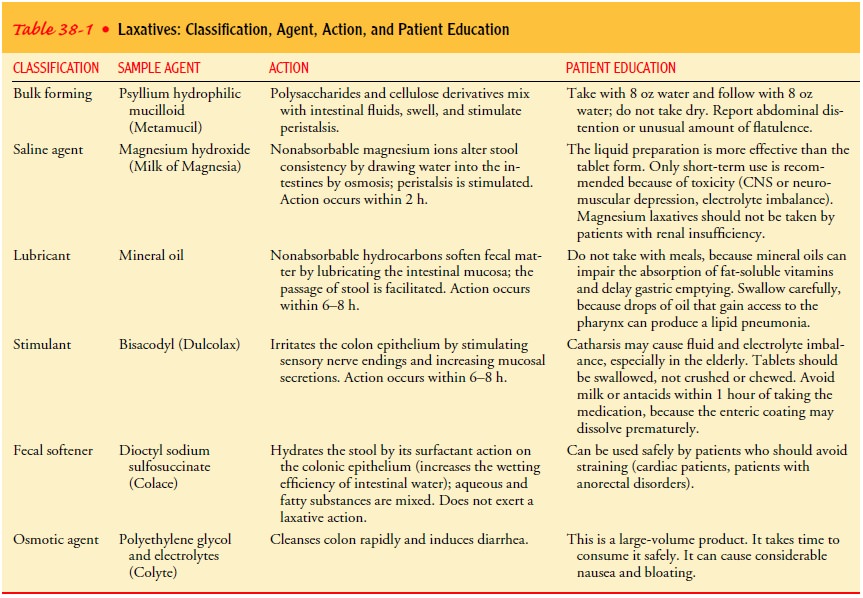

Medical Management

Treatment

is aimed at the underlying cause of constipation and includes education, bowel

habit training, increased fiber and fluid intake, and judicious use of

laxatives. Management may also in-clude discontinuing laxative abuse. Routine

exercise to strengthen abdominal muscles is encouraged. Biofeedback is a

technique that can be used to help patients learn to relax the sphincter

mecha-nism to expel stool. Daily addition to the diet of 6 to 12 tea-spoonfuls

of unprocessed bran is recommended, especially for the treatment of

constipation in the elderly. If laxative use is necessary, one of the following

may be prescribed: bulk-forming agents, saline and osmotic agents, lubricants,

stimulants, or fecal soften-ers. The physiologic action and patient education

information re-lated to these laxatives are identified in Table 38-1. Enemas

and rectal suppositories are generally not recommended for constipa-tion and

should be reserved for the treatment of impaction or for preparing the bowel

for surgery or diagnostic procedures. If long-term laxative use is necessary, a

bulk-forming agent may be pre-scribed in combination with an osmotic laxative.

Doctors

prescribe the use of specific medications to enhance colonic transit by

increasing propulsive motor activity. Further studies are being carried out on

cholinergic agents (eg, bethane-chol), cholinesterase inhibitors (eg,

neostigmine), and prokinetic agents (eg, metoclopramide) to determine the role

these agents can play in treating constipation (Yamada et al., 1999).

Nursing Management

The

nurse elicits information about the onset and duration of con-stipation,

current and past elimination patterns, the patient’s ex-pectation of normal

bowel elimination, and lifestyle information (eg, exercise and activity level,

occupation, food and fluid intake, and stress level) during the health history

interview. Past medical and surgical history, current medications, and laxative

and enema use are important, as is information about the sensation of rectal

pressure or fullness, abdominal pain, excessive straining at defeca-tion, and

flatulence.

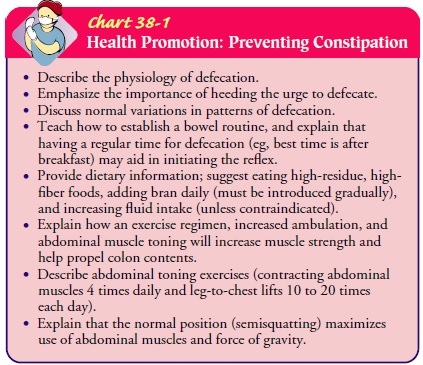

Patient

education and health promotion are important functions of the nurse (Chart

38-1). After the health history is obtained, the nurse sets specific goals for

teaching. Goals for the patient include restoring or maintaining a regular

pattern of elimination, ensur-ing adequate intake of fluids and high-fiber

foods, learning about methods to avoid constipation, relieving anxiety about

bowel elimination patterns, and avoiding complications.

Related Topics