Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Intestinal and Rectal Disorders

Diverticular Disease - Acute Inflammatory Intestinal Disorders

DIVERTICULAR

DISEASE

A diverticulum is a saclike outpouching

of the lining of the bowel that extends through a defect in the muscle layer.

Diverticula may occur anywhere along the GI tract. Diverticulosis exists when mul-tiple diverticula are present

without inflammation or symptoms. Diverticular disease of the colon is very

common in developed countries, and its prevalence increases with age. More than

35% of Americans older than 60 years of age have diverticulosis. The incidence

increases to 50% among those in the ninth decade of life (Keighley, 1999). Diverticulitis results when food and

bacteria retained in a diverticulum produce infection and inflammation that can

impede drainage and lead to perforation or abscess for-mation. Diverticulitis

is most common (95%) in the sigmoid colon. Approximately 20% of patients with

diverticulosis have di-verticulitis at some point. A congenital predisposition

is suspected when the disorder occurs in those younger than 40 years of age. A

low intake of dietary fiber is considered a predisposing factor, but the exact

cause is unknown. Diverticulitis may occur in acute at-tacks or may persist as

a continuing, smoldering infection. Most patients remain entirely asymptomatic.

The symptoms manifested generally result from its potential

complications—abscesses, fistu-las, obstruction, and hemorrhage.

Pathophysiology

A

diverticulum forms when the mucosa and submucosal layers of the colon herniate

through the muscular wall because of high intraluminal pressure, low volume in

the colon (ie, fiber-deficient contents), and decreased muscle strength in the

colon wall (ie, muscular hypertrophy from hardened fecal masses). Bowel

contents can accumulate in the diverticulum and decompose, causing inflammation

and infection. A diverticulum can become ob-structed and then inflamed if the

obstruction continues. The in-flammation tends to spread to the surrounding

bowel wall, giving rise to irritability and spasticity of the colon (ie,

diverticulitis). Ab-scesses develop and may eventually perforate, leading to

peritoni-tis and erosion of the blood vessels (arterial) with bleeding.

Clinical Manifestations

Chronic

constipation often precedes the development of diver-ticulosis by many years.

Frequently, no problematic symptoms occur with diverticulosis. Signs of acute

diverticulosis are bowel irregularity and intervals of diarrhea, abrupt onset

of crampy pain in the left lower quadrant of the abdomen, and a low-grade

fever. The patient may have nausea and anorexia, and some bloating or abdominal

distention may occur. With repeated local inflamma-tion of the diverticula, the

large bowel may narrow with fibrotic strictures, leading to cramps, narrow

stools, and increased con-stipation. Weakness, fatigue, and anorexia are common

symp-toms. With acute diverticulosis, the patient reports mild to severe pain

in the lower left quadrant. The condition, if untreated, can lead to

septicemia.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

A CT

scan is the procedure of choice and can reveal abscesses. Ab-dominal x-ray

findings may demonstrate free air under the di-aphragm if a perforation has

occurred from the diverticulitis. Diverticulosis may be diagnosed using barium

enema, which shows narrowing of the colon and thickened muscle layers. If there

are symptoms of peritoneal irritation and when the diag-nosis is

diverticulitis, barium enema is contraindicated because of the potential for

perforation.

A colonoscopy may be performed if there is no acute diver-ticulitis or after resolution of an acute episode to visualize the colon, determine the extent of the disease, and rule out other con-ditions. Laboratory tests that assist in diagnosis include a com-plete blood cell count, revealing an elevated leukocyte count, and elevated sedimentation rate.

Complications

Complications of diverticulitis include

peritonitis, abscess forma-tion, and bleeding. If an abscess develops, the

associated findings are tenderness, a palpable mass, fever, and leukocytosis.

An in-flamed diverticulum that perforates results in abdominal pain lo-calized

over the involved segment, usually the sigmoid; local abscess or peritonitis

follows. Abdominal pain, a rigid boardlike abdomen, loss of bowel sounds, and

signs and symptoms of shock occur with peritonitis. Noninflamed or slightly

inflamed diverticula may erode areas adjacent to arterial branches, causing

massive rectal bleeding.

Gerontologic Considerations

The

incidence of diverticular disease increases with age because of degeneration

and structural changes in the circular muscle layers of the colon and because

of cellular hypertrophy. The symptoms are less pronounced in the elderly than

in other adults. The elderly may not have abdominal pain until infection

occurs. They may delay re-porting symptoms because they fear surgery or are

afraid that they may have cancer. Blood in the stool is overlooked frequently,

espe-cially in the elderly, because of a failure to examine the stool or the

inability to see changes because of diminished vision.

Medical Management

DIETARY AND MEDICATION MANAGEMENT

Diverticulitis

can usually be treated on an outpatient basis with diet and medicine therapy.

When symptoms occur, rest, analgesics, and antispasmodics are recommended.

Initially, the diet is clear liquid until the inflammation subsides; then, a

high-fiber, low-fat diet is recommended. This type of diet helps to increase

stool volume, decrease colonic transit time, and reduce intraluminal pressure.

Antibiotics are prescribed for 7 to 10 days. A bulk-forming laxative also is

prescribed.

In

acute cases of diverticulitis with significant symptoms, hos-pitalization is

required. Hospitalization is often indicated for those who are elderly,

immunocompromised, or taking corticosteroids. Withholding oral intake,

administering intravenous fluids, and in-stituting nasogastric suctioning if

vomiting or distention occurs rests the bowel. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are

prescribed for 7 to 10 days. An opioid is prescribed for pain relief; morphine

is not used because it increases segmentation and intraluminal pressures. Oral

intake is increased as symptoms subside. A low-fiber diet may be necessary

until signs of infection decrease.

Antispasmodics

such as propantheline bromide (Pro-Banthine) and oxyphencyclimine (Daricon) may

be prescribed. Normal stools can be achieved by using bulk preparations

(Metamucil) or stool softeners (Colace), by instilling warm oil into the

rectum, or by in-serting an evacuant suppository (Dulcolax). Such a

prophylactic plan can reduce the bacterial flora of the bowel, diminish the

bulk of the stool, and soften the fecal mass so that it moves more easily

through the area of inflammatory obstruction.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Although

acute diverticulitis usually subsides with medical man-agement, immediate

surgical intervention is necessary if complica-tions (eg, perforation,

peritonitis, abscess formation, hemorrhage, obstruction) occur. Alternatively,

when the acute episode of diver-ticulitis resolves, surgery may be recommended

to prevent repeated episodes. Two types of surgery are considered:

•

One-stage resection in which the inflamed area is

removed and a primary end-to-end anastomosis is completed

•

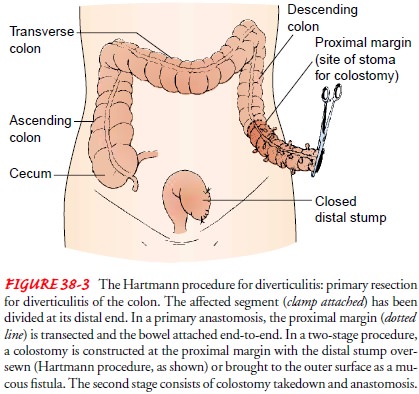

Multiple-staged procedures for complications such

as ob-struction or perforation (Fig. 38-3)

The

type of surgery performed depends on the extent of com-plications found during

surgery. When possible, the area of di-verticulitis is resected and the

remaining bowel is joined end to end (ie, primary resection and end-to-end

anastomosis). This is performed through traditional surgical or

laparoscopically as-sisted colectomy. A two-stage resection may be performed in

which the diseased colon is resected (as in a one-stage procedure) but no

anastomosis is performed; both ends of the bowel are brought out onto the

abdomen as stomas. This “double-barrel” colostomy is then reanastomosed in a

later procedure.

Related Topics