Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Intestinal and Rectal Disorders

Nursing Management of the Patient Requiring an Ileostomy

NURSING

MANAGEMENT OF THE PATIENT REQUIRING AN ILEOSTOMY

Some

patients with IBD eventually require permanent fecal di-version with creation

of an ileostomy to manage symptoms and to treat or prevent complications. The

Plan of Nursing Care 38-1 summarizes care for the patient requiring an ostomy.

Providing Preoperative Care

A

period of preparation with intensive replacement of fluid, blood, and protein

is necessary before surgery is performed. Anti-biotics may be prescribed. If

the patient has been taking corti-costeroids, they will be continued during the

surgical phase to prevent steroid-induced adrenal insufficiency. Usually, the

patient is given a low-residue diet, provided in frequent, small feedings. All

other preoperative measures are similar to those for general abdominal surgery.

The abdomen is marked for the proper place-ment of the stoma by the surgeon or

the enterostomal therapist. Care is taken to ensure that the ostomy stoma is

conveniently placed–usually in the right lower quadrant about 2 inches below

the waist, in an area away from previous scars, bony prominence, skin folds, or

fistulas.

The

patient must have a thorough understanding of the surgery to be performed and

what to expect after surgery. Infor-mation about an ileostomy is presented to

the patient by means of written materials, models, and discussion. Preoperative

teach-ing includes management of drainage from the stoma, the nature of

drainage, and the need for nasogastric intubation, parenteral fluids, and

possibly perineal packing.

Providing Postoperative Care

General

abdominal surgery wound care is required. The nurse observes the stoma for

color and size. It should be pink to bright red and shiny. For the traditional

ileostomy, a tempo-rary plastic bag with adhesive facing is placed over the

ileostomy and firmly pressed onto surrounding skin. The nurse monitors the

ileostomy for fecal drainage, which should begin about 72 hours after surgery.

The drainage is a continuous liq-uid from the small intestine because the stoma

does not have a controlling sphincter. The contents drain into the plastic bag

and are thus kept from coming into contact with the skin. They are collected

and measured when the bag becomes full. If a continent ileal reservoir was

created, as described for the Kock pouch, continuous drainage is provided by an

indwelling reservoir catheter for 2 to 3 weeks after surgery. This allows the

suture lines to heal.

As

with other patients undergoing abdominal surgery, the nurse encourages those

with an ileostomy to engage in early am-bulation. It is important to administer

prescribed pain medica-tions as required.

Because

these patients lose much fluid in the early post-operative period, an accurate

record of fluid intake, urinary output, and fecal discharge is necessary to

help gauge the fluid needs of the patient. There may be 1000 to 2000 mL of

fluid lost each day in addition to expected fluid loss through urine,

perspiration, respiration, and other sources. With this loss, sodium and

potassium are depleted. The nurse monitors labo-ratory values and administers

electrolyte replacements as pre-scribed. Intravenous fluids are administered to

replace fluid losses for 4 to 5 days.

Nasogastric

suction is also a part of immediate postoperative care, with the tube requiring

frequent irrigation, as prescribed. The purpose of nasogastric suction is to

prevent a buildup of gas-tric contents. After the tube is removed, the nurse

offers sips of clear liquids and gradually progresses the diet. It is important

to immediately report nausea and abdominal distention, which may indicate

obstruction.

By the

end of the first week, rectal packing is removed. Because this procedure may be

uncomfortable, the nurse may administer an analgesic an hour before it is

performed. After the packing is removed, the perineum is irrigated two or three

times daily until full healing takes place.

PROVIDING EMOTIONAL SUPPORT

The patient understandably may think that everyone is aware of the ileostomy and may view the stoma as a mutilation compared with other abdominal incisions that heal and are hidden.

Because there

is loss of a body part and a major change in anatomy, the patient often goes

through the various phases of grieving—shock, disbelief, denial, rejection,

anger, and restitution. Nursing sup-port through these phases is important, and

understanding of the patient’s emotional outlook in each instance should

determine the approach taken. For example, teaching may be ineffective until

the patient is ready to learn. Concern about body image may lead to questions

related to family relationships, sexual function, and for women, the ability to

become pregnant and to deliver a baby normally. Patients need to know that

someone understands and cares about them. A calm, nonjudgmental attitude

exhibited by the nurse aids in gaining the patient’s confidence. It is

impor-tant to recognize the dependency needs of these patients. Their prolonged

illness can make them irritable, anxious, and depressed. The nurse can coordinate

patient care through meetings attended by consultants such as the physician,

psychologist, psy-chiatrist, social worker, enterostomal therapist, and

dietitian. The team approach is important in facilitating the often complex

care of this patient.

Conversely,

a surgical procedure to create an ileostomy can produce dramatic positive

changes in patients who have suffered from IBD for several years. After the

continuous discomfort of the disease has decreased and patients learn how to

take care of the ileostomy, they often develop a more positive outlook. Until

they progress to this phase, an empathetic and tolerant approach by the nurse

plays an important part in recovery. The sooner the patient masters the

physical care of the ileostomy, the sooner he or she will psychologically

accept it.

The

support of other ostomates is also helpful. The United Ostomy Association is

dedicated to the rehabilitation of osto-mates. This organization gives patients

useful information about living with an ostomy through an educational program

of litera-ture, lectures, and exhibits. Local associations offer visiting

ser-vices by qualified members who provide hope and rehabilitation services to

new ostomy patients. Hospitals and other health care agencies may have an

enterostomal therapy nurse on staff who can serve as a valuable resource person

for the ileostomy patient.

MANAGING SKIN AND STOMA CARE

The

patient with a traditional ileostomy cannot establish regular bowel habits

because the contents of the ileum are fluid and are discharged continuously.

The patient must wear a pouch at all times. Stomal size and pouch size vary

initially; the stoma should be rechecked 3 weeks after surgery, when the edema

has subsided. The final size and type of appliance is selected in 3 months,

after the patient’s weight has stabilized, and the stoma shrinks to a sta-ble

shape.

The

location and length of the stoma are significant in the man-agement of the

ileostomy by the patient. The surgeon positions the stoma as close to the

midline as possible and at a location where even an obese patient with a

protruding abdomen can care for it easily. Usually, the ileostomy stoma is

about 2.5 cm (1 in) long, which makes it convenient for the attachment of an

appliance.

Skin

excoriation around the stoma can be a persistent problem. Peristomal skin

integrity may be compromised by several factors, such as an allergic reaction

to the ostomy appliance, skin barrier, or paste; chemical irritation from the

effluent; mechanical injury from the removal of the appliance; and possible

infection. If irri-tation and yeast growth occur, nystatin powder (Mycostatin)

is dusted lightly on the peristomal skin.

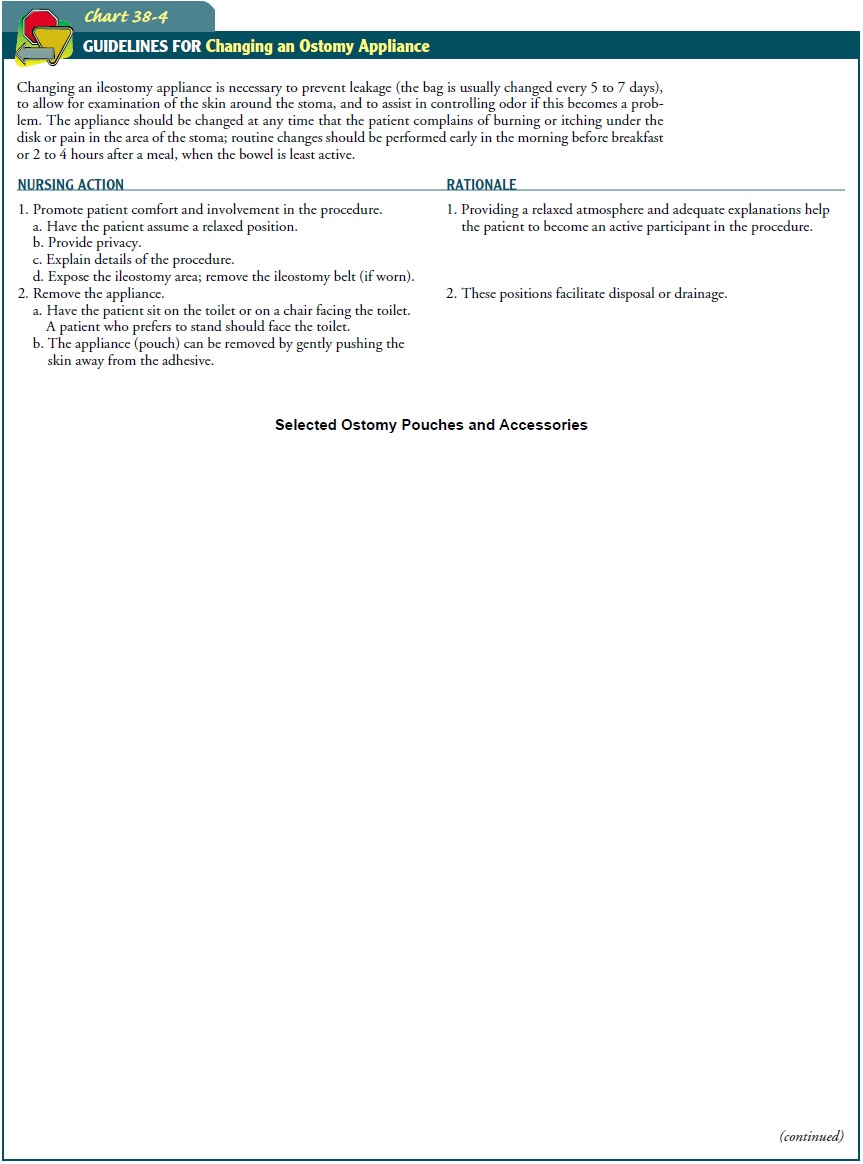

CHANGING AN APPLIANCE

A

regular schedule for changing the pouch before leakage occurs must be

established for those with a traditional ileostomy. The patient can be taught

to change the pouch in a manner similar to that described in Chart 38-4.

The

amount of time a person can keep the appliance sealed to the body surface

depends on the location of the stoma and on body structure. The usual wearing

time is 5 to 7 days. The appli-ance is emptied every 4 to 6 hours or at the

same time the patient empties the bladder. An emptying spout at the bottom of

the ap-pliance is closed with a special clip made for this purpose.

Most

pouches are disposable and odor-proof. Foods such as spinach and parsley act as

deodorizers in the intestinal tract; foods that cause odors include cabbage,

onions, and fish. Bismuth sub-carbonate tablets, which may be prescribed and

taken by mouth three or four times each day, are effective in reducing odor. A

stool thickener, such as diphenoxylate (Lomotil), can also be prescribed and

taken orally to assist in odor control.

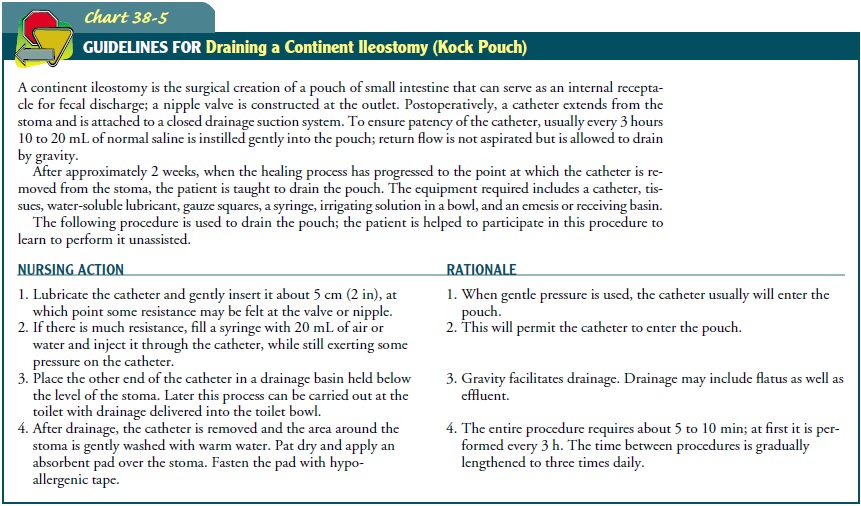

IRRIGATING A CONTINENT ILEOSTOMY

For a

continent ileostomy (ie, Kock pouch), the nurse teaches the patient to drain

the pouch, as described in Chart 38-5. A catheter is inserted into the

reservoir to drain the fluid. The length of time between drainage periods is

gradually increased until the reservoir needs to be drained only every 4 to 6

hours and irrigated once each day. A pouch is not necessary; instead, most

patients wear a small dressing over the opening.

When

the fecal discharge is thick, water can be injected through the catheter to

loosen and soften it. The consistency of the effluent is affected by food

intake. At first, drainage is only 60 to 80 mL, but as time goes on, the amount

increases significantly. The internal Kock pouch stretches, eventually

accommodating 500 to 1000 mL. The patient learns to use the sensation of

pressure in the pouch as a gauge to determine how often the pouch should be

drained.

MANAGING DIETARY AND FLUID NEEDS

A

low-residue diet is followed for the first 6 to 8 weeks. Strained fruits and

vegetables are given. These foods are important sources of vitamins A and C.

Later, there are few dietary restrictions, ex-cept for avoiding foods that are

high in fiber or hard-to-digest kernels, such as celery, popcorn, corn, poppy

seeds, caraway seeds, and coconut. Foods are reintroduced one at a time. The

nurse assesses the patient’s tolerance for these foods and reminds him or her

to chew food thoroughly.

Fluids

may be a problem during the summer, when fluid lost through perspiration adds

to the fluid loss through the ileostomy. Fluids such as Gatorade are helpful in

maintaining the electrolyte balance. If the fecal discharge is too watery,

fibrous foods (eg, whole-grain cereals, fresh fruit skins, beans, corn, nuts)

are re-stricted. If the effluent is excessively dry, salt intake is increased.

Increased intake of water or fluid does not increase the effluent, because

excess water is excreted in the urine.

PREVENTING COMPLICATIONS

Monitoring

for complications is an ongoing activity for the pa-tient with an ileostomy.

Minor complications occur in about 40% of patients who have an ileostomy; less

than 20% of the compli-cations require surgical intervention (Kirsner &

Shorter, 2000).

Common

complications include skin irritation, diarrhea, stomal stenosis, urinary

calculi, and cholelithiasis. Peristomal skin irritation, the most common

complication of an ileostomy, re-sults from leakage of effluent. A pouch that

does not fit well is often the cause. The nurse or an enterostomal therapist

adjusts the pouch and skin barriers are applied. Diarrhea, manifested by very

irritating effluent that rapidly fills the pouch (every hour or sooner), can

quickly lead to dehydration and electrolyte losses. Supplemental water, sodium,

and potassium are administered to prevent hypovolemia and hypokalemia.

Antidiarrheal agents are administered. Stenosis is caused by circular scar

tissue that forms at the stoma site. The scar tissue must be surgically

released. Uri-nary calculi occur in about 10% of ileostomy patients because of

dehydration from decreased fluid intake. Intense lower abdominal pain that

radiates to the legs, hematuria, and signs of dehydration indicate that the

urine should be strained. Fluid intake is en-couraged. Sometimes, small stones

are passed during urination; otherwise, treatment is necessary to crush or remove

the calculi.

Cholelithiasis (ie, gallstones) occurs three times more com-monly in patients with an ileostomy than in the general population because of changes in the absorption of bile acids that occur post-operatively. Spasm of the gallbladder causes severe upper right abdominal pain that can radiate to the back and right shoulder.

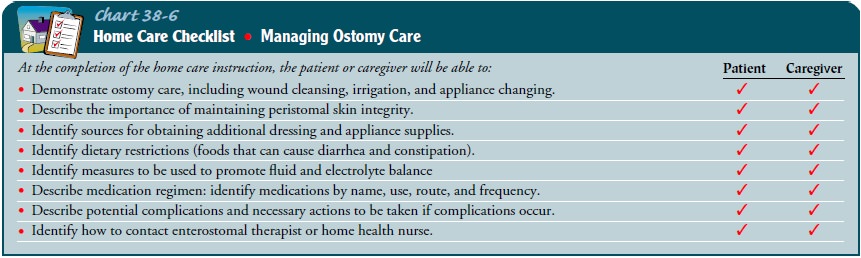

PROMOTING HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED CARE

Teaching Patients Self-Care

The

spouse and family should be familiar with the adjustment that will be necessary

when the patient returns home. They need to know why it is necessary for the

patient to occupy the bathroom for 10 minutes or more at certain times of the

day and why cer-tain equipment is needed. Their understanding is necessary to

reduce tension; a relaxed patient tends to have fewer problems. Vis-its from an

enterostomal therapy nurse may be arranged to ensure that the patient is

progressing as expected and to provide additional guidance and teaching as

needed.

The

patient needs to know the commercial name of the pouch to be used so that he or

she can obtain a ready supply and should have information about obtaining other

supplies. The names and contact information of the local enterostomal therapy nurse

and local self-help groups are often helpful. Any special restrictions on

driving or working also need to be reviewed. The nurse teaches the patient

about common postoperative complications and how to recognize and report them

(Chart 38-6).

Related Topics