Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Intestinal and Rectal Disorders

Diseases of the Anorectum

Diseases of the Anorectum

Anorectal

disorders are common, and more than one half of the population will experience

one at some time during their lives (Yamada et al., 1999). Patients with

anorectal disorders seek medical care primarily because of pain, rectal

bleeding, or change in bowel habits. Other common complaints are protrusion of

hemorrhoids, anal discharge, perianal itching, swelling, anal ten-derness,

stenosis, and ulceration. Constipation results from delay-ing defecation

because of anorectal pain.

There

has been a steady increase in the frequency of sexually transmitted diseases in

recent decades, leading to the identifica-tion of new anorectal syndromes. The

prevalence of these condi-tions is increasing. These syndromes include venereal

infections such as syphilis, gonorrhea, herpes, chlamydia, and candidiasis, and

they are most commonly seen in male homosexuals who practice anorectal

intercourse (Wolfe, 2000).

ANORECTAL ABSCESS

An

anorectal abscess is caused by obstruction of an anal gland, resulting in

retrograde infection. People with regional enteritis or immunosuppressive

conditions such as AIDS are particularly susceptible to these infections. Many

of these abscesses result in fistulas.

An

abscess may occur in a variety of spaces in and around the rectum. It often

contains a quantity of foul-smelling pus and is painful. If the abscess is

superficial, swelling, redness, and ten-derness are observed. A deeper abscess

may result in toxic symp-toms, lower abdominal pain, and fever.

Palliative

therapy consists of sitz baths and analgesics. How-ever, prompt surgical

treatment to incise and drain the abscess is the treatment of choice. When a

deeper infection exists with the possibility of a fistula, the fistulous tract

must be excised. If pos-sible, the fistula is excised when the abscess is

incised and drained, or a second procedure to do so may be necessary. The wound

may be packed with gauze and allowed to heal by granulation.

ANAL FISTULA

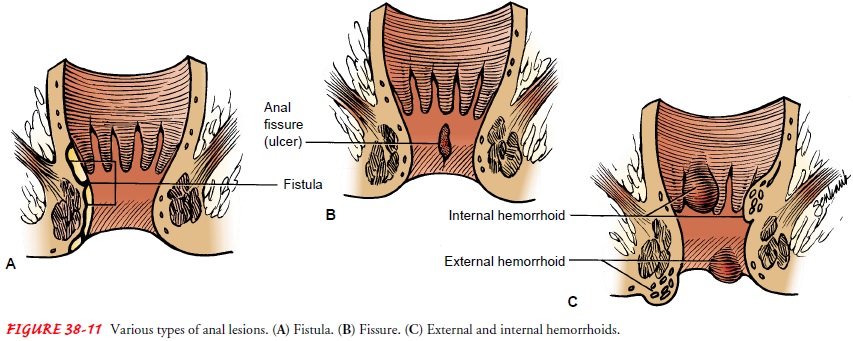

An

anal fistula is a tiny, tubular, fibrous tract that extends into the anal canal

from an opening located beside the anus (Fig. 38-11A). Fistulas usually result

from an infection. They may also develop from trauma, fissures, or regional

enteritis. Pus or stool may leak constantly from the cutaneous opening. Other

symptoms may be the passage of flatus or feces from the vagina or bladder,

depend-ing on the fistula tract. Untreated fistulas may cause systemic

in-fection with related symptoms.

Surgery

is always recommended, because few fistulas heal spon-taneously. A fistulectomy

(ie, excision of the fistulous tract) is the recommended surgical procedure.

The lower bowel is evacuated thoroughly with several prescribed enemas. During

surgery, the sinus tract is identified by inserting a probe into it or by

injecting the tract with methylene blue solution. The fistula is dissected out

or laid open by an incision from its rectal opening to its outlet. The wound is

packed with gauze.

ANAL FISSURE

An anal fissure is a longitudinal tear or

ulceration in the lining of the anal canal (see Fig. 38-11B). Fissures are

usually caused by the trauma of passing a large, firm stool or from persistent

tightening of the anal canal because of stress and anxiety (leading to

constipation). Other causes include childbirth, trauma, and overuse of

laxatives.

Extremely painful defecation, burning, and

bleeding character-ize fissures. Most of these fissures heal if treated by

conservative mea-sures, which include stool softeners and bulk agents, an

increase in water intake, sitz baths, and emollient suppositories. A

suppository combining an anesthetic with a corticosteroid helps relieve the

dis-comfort. Anal dilation under anesthesia may be required.

If

fissures do not respond to conservative treatment, surgery is indicated. The

procedure considered by most surgeons to be the procedure of choice is the

lateral internal sphincterotomy with excision of the fissure; the success rate

is 90% to 95% (Rieghley, 1999).

HEMORRHOIDS

Hemorrhoids are dilated portions of veins in the anal canal. They are very common. By the age of 50, about 50% of people have hemorrhoids to some extent (Corman, 1998).

Shearing of the mucosa

during defecation results in the sliding of the structures in the wall of the

anal canal, including the hemorrhoidal and vascular tissues. Increased pressure

in the hemorrhoidal tissue due to pregnancy may initiate hemorrhoids or

aggravate existing ones. Hemorrhoids are classified as one of two types. Those

above the internal sphincter are called internal hemorrhoids, and those

appearing outside the external sphincter are called external hem-orrhoids (see

Fig. 38-11C).

Hemorrhoids

cause itching and pain and are the most common cause of bright red bleeding

with defecation. External hemor-rhoids are associated with severe pain from the

inflammation and edema caused by thrombosis (ie, clotting of blood within the

hem-orrhoid). This may lead to ischemia of the area and eventual necrosis.

Internal hemorrhoids are not usually painful until they bleed or prolapse when

they become enlarged.

Hemorrhoid

symptoms and discomfort can be relieved by good personal hygiene and by avoiding

excessive straining during defecation. A high-residue diet that contains fruit

and bran along with an increased fluid intake may be all the treatment that is

necessary to promote the passage of soft, bulky stools to prevent straining. If

this treatment is not successful, the addition of hy-drophilic bulk-forming

agents such as psyllium and mucilloid may help. Warm compresses, sitz baths,

analgesic ointments and suppositories, astringents (eg, witch hazel), and bed

rest allow the engorgement to subside.

There

are several types of nonsurgical treatments for hemor-rhoids. Infrared

photocoagulation, bipolar diathermy, and laser therapy are newer techniques

that are used to affix the mucosa to the underlying muscle. Injecting

sclerosing solutions is also ef-fective for small, bleeding hemorrhoids. These

procedures help prevent prolapse.

A

conservative surgical treatment of internal hemorrhoids is the rubber-band

ligation procedure. The hemorrhoid is visual-ized through the anoscope, and its

proximal portion above the mucocutaneous lines is grasped with an instrument. A

small rub-ber band is then slipped over the hemorrhoid. Tissue distal to the

rubber band becomes necrotic after several days and sloughs off. Fibrosis

occurs; the result is that the lower anal mucosa is drawn up and adheres to the

underlying muscle. Although this treat-ment has been satisfactory for some

patients, it has proven painful for others and may cause secondary hemorrhage.

It has been known to cause perianal infection.

Cryosurgical

hemorrhoidectomy, another method for re-moving hemorrhoids, involves freezing

the hemorrhoid for a sufficient time to cause necrosis. Although it is

relatively pain-less, this procedure is not widely used because the discharge

is very foul smelling and wound healing is prolonged. The Nd:YAG laser is

useful in excising hemorrhoids, particularly external hemorrhoidal tags. The

treatment is quick and rela-tively painless. Hemorrhage and abscess are rare

postoperative complications.

The

previously described methods of treating hemorrhoids are not effective for

advanced thrombosed veins, which must be treated by more extensive surgery.

Hemorrhoidectomy, or surgi-cal excision, can be performed to remove all the

redundant tissue involved in the process. During surgery, the rectal sphincter

is usually dilated digitally and the hemorrhoids are removed with a clamp and

cautery or are ligated and then excised. After the op-erative procedures are

completed, a small tube may be inserted through the sphincter to permit the escape

of flatus and blood; pieces of Gelfoam or Oxycel gauze may be placed over the

anal wounds.

SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED ANORECTAL DISEASES

Three infectious syndromes that are related

to sexually transmitted diseases have been identified. Proctitis involves the

rectum. It is commonly associated with recent anal-receptive intercourse with

an infected partner. Symptoms include a mucopurulent discharge or bleeding,

pain in the area, and diarrhea. The pathogens most fre-quently involved are Neisseria gonorrheae (53%), Chlamydia (20%), herpes simplex virus

(18%), and Treponema pallidium (9%)

(Yamada et al., 1999). Proctocolitis involves the rectum and lowest portion of

the descending colon. Symptoms are similar to proctitis but may also include

watery or bloody diarrhea, cramps, pain, and bloating. Enteritis involves more

of the descending colon, and symp-toms include watery, bloody diarrhea;

abdominal pain; and weight loss. The most common pathogens causing enteritis

are E. histolyt-ica, Giardia lamblia,

Shigella, and Campylobacter (Wolfe,

2000).

Sigmoidoscopy

is performed to identify portions of the anorec-tum involved. Samples are taken

with rectal swabs, and cultures are obtained to identify the pathogens

involved. The treatment of choice for bacterial infections is antibiotics (ie,

cefixime, doxycy-cline, and penicillin). Acyclovir is given to those with viral

infec-tions. Infections from E.

histolytica and G. lamblia are

treated with antiamebic therapy (ie, metronidazole). Ciprofloxacin is an

effec-tive treatment for Shigella.

Antibiotics of choice for Campylobacter

infection are erythromycin and ciprofloxacin.

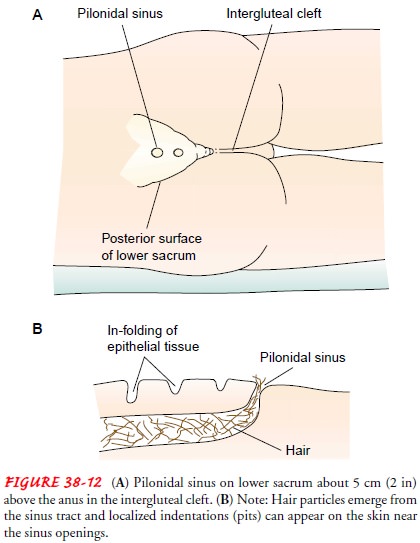

PILONIDAL SINUS OR CYST

A pilonidal sinus or cyst is found in the intergluteal cleft on the posterior surface of the lower sacrum (Fig. 38-12). Current the-ories suggest that it results from local trauma that causes the penetration of hairs into the epithelium and subcutaneous tissue (Yamada et al., 1999).

It

may also be formed congenitally by an infolding of epithelial tissue beneath

the skin, which may com-municate with the skin surface through one or several

small sinus openings. Hair frequently is seen protruding from these open-ings,

and this gives the cyst its name, pilonidal

(ie, a nest of hair). The cysts rarely cause symptoms until adolescence or

early adult life, when infection produces an irritating drainage or an abscess.

Perspiration and friction easily irritate this area.

In the

early stages of the inflammation, the infection may be controlled by antibiotic

therapy, but after an abscess has formed, surgery is indicated. The abscess is

incised and drained under local anesthesia. After the acute process resolves,

further surgery is performed to excise the cyst and the secondary sinus tracts.

The wound is allowed to heal by granulation. Gauze dressings are placed in the

wound to keep its edges separated while heal-ing occurs.

Related Topics