Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Intestinal and Rectal Disorders

Colorectal Cancer

COLORECTAL

CANCER

Tumors

of the colon and rectum are relatively common; the col-orectal area (the colon

and rectum combined) is now the third most common site of new cancer cases and

deaths in the United States. Colorectal cancer is a disease of Western

cultures; there were an estimated 148,300 new cases and 56,000 deaths from the

disease in 2002 (American Cancer Society, 2002).

The

incidence increases with age (the incidence is highest for people older than 85

years of age) and is higher for people with a family history of colon cancer

and those with IBD or polyps. The exact cause of colon and rectal cancer is

still unknown, but risk factors have been identified (Chart 38-7).

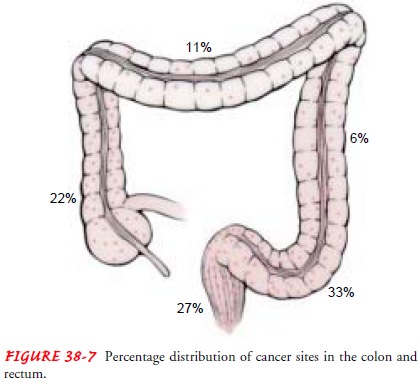

The

distribution of cancer sites throughout the colon is shown in Figure 38-7

(Goldman, & Bennett, 2000). Changes in this dis-tribution have occurred in

recent years. The incidence of cancer in the sigmoid and rectal areas has

decreased, whereas the inci-dence of cancer in the cecum, ascending, and

descending colon has increased.

Improved

screening strategies have helped to reduce the num-ber of deaths in recent

years. Of the more than 148,000 people diagnosed each year, fewer than half

that number die annually (Beyers et al., 2001). Early diagnosis and prompt treatment

could save almost three of every four people with colorectal cancer. If the

disease is detected and treated at an early stage, the 5-year sur-vival rate is

90%, but only 34% of colorectal cancers are found at an early stage. Survival

rates after late diagnosis are very low. Most people are asymptomatic for long

periods and seek health care only when they notice a change in bowel habits or

rectal bleed-ing. Prevention and early screening are key to detection and

re-duction of mortality rates.

Pathophysiology

Cancer

of the colon and rectum is predominantly (95%) ade-nocarcinoma (ie, arising

from the epithelial lining of the intes-tine). It may start as a benign polyp

but may become malignant, invade and destroy normal tissues, and extend into

surrounding structures. Cancer cells may break away from the primarytumor and

spread to other parts of the body (most often to the liver).

Clinical Manifestations

The

symptoms are greatly determined by the location of the cancer, the stage of the

disease, and the function of the intesti-nal segment in which it is located.

The most common present-ing symptom is a change in bowel habits. The passage of

blood in the stools is the second most common symptom. Symptoms may also

include unexplained anemia, anorexia, weight loss, and fatigue.

The

symptoms most commonly associated with right-sided le-sions are dull abdominal

pain and melena (ie, black, tarry stools). The symptoms most commonly

associated with left-sided lesions are those associated with obstruction (ie, abdominal

pain and cramping, narrowing stools, constipation, and distention), as well as

bright red blood in the stool. Symptoms associated with rectal lesions are

tenesmus (ie, ineffective, painful straining at stool), rec-tal pain, the

feeling of incomplete evacuation after a bowel move-ment, alternating

constipation and diarrhea, and bloody stool.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Along

with an abdominal and rectal examination, the most im-portant diagnostic

procedures for cancer of the colon are fecal oc-cult blood testing, barium

enema, proctosigmoidoscopy, and colonoscopy. As many as 60% of colorectal

cancer cases can be identified by sigmoidoscopy with biopsy or cytology smears

(Yamada et al., 1999).

Carcinoembryonic

antigen (CEA) studies may also be per-formed. Although CEA may not be a highly

reliable indicator in diagnosing colon cancer because not all lesions secrete

CEA, stud-ies show that CEA levels are reliable in predicting prognosis. With

complete excision of the tumor, the elevated levels of CEA should return to

normal within 48 hours. Elevations of CEA at a later date suggest recurrence

(Yamada et al., 1999).

Complications

Tumor

growth may cause partial or complete bowel obstruction. Extension of the tumor

and ulceration into the surrounding blood vessels results in hemorrhage.

Perforation, abscess formation, peri-tonitis, sepsis, and shock may occur.

Gerontologic Considerations

The

incidence of carcinoma of the colon and rectum increases with age. These

cancers are considered common malignancies in advanced age. Only prostate

cancer and lung cancer in men exceed colorectal cancer. Among women, only

breast cancer exceeds the incidence of colorectal cancer (Lueckenotte, 2000).

Symptoms are often insidious. Cancer patients usually report fatigue, which is

caused primarily by iron-deficiency anemia. In early stages, minor changes in

bowel patterns and occasional bleeding may occur. The later symptoms most

commonly reported by the elderly are abdominal pain, obstruction, tenesmus, and

rectal bleeding.

Colon

cancer in the elderly has been closely associated with di-etary carcinogens.

Lack of fiber is a major causative factor because the passage of feces through

the intestinal tract is prolonged, which extends exposure to possible

carcinogens. Excess fat is be-lieved to alter bacterial flora and convert

steroids into compounds that have carcinogenic properties.

Medical Management

The

patient with symptoms of intestinal obstruction is treated with intravenous

fluids and nasogastric suction. If there has been significant bleeding, blood

component therapy may be required.

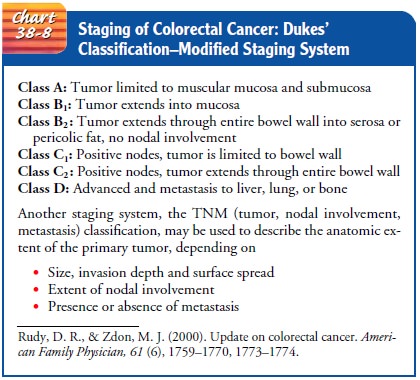

Treatment

for colorectal cancer depends on the stage of the disease (Chart 38-8) and

consists of surgery to remove the tumor, supportive therapy, and adjuvant

therapy. Data demonstrate de-lays in tumor recurrence and increases in survival

time for patients who receive some form of adjuvant therapy—chemotherapy,

radiation therapy, immunotherapy, or multimodality therapy.

ADJUVANT THERAPY

The

standard adjuvant therapy administered to patients with Dukes’ class C colon

cancer is the 5-fluorouracil plus levamisole regimen (Wolfe, 2000). Patients

with Dukes’ class B or C rectal cancer are given 5-fluorouracil and high doses

of pelvic irradia-tion. Mitomycin is also used. Radiation therapy is used

before, during, and after surgery to shrink the tumor, to achieve better

results from surgery, and to reduce the risk of recurrence. For in-operative or

unresectable tumors, irradiation is used to provide significant relief from

symptoms. Intracavity and implantable devices are used to deliver radiation to

the site. The response to adjuvant therapy varies.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgery is the primary treatment for most colon and rectal can-cers. It may be curative or palliative. Advances in surgical tech-niques can enable the patient with cancer to have sphincter-saving devices that restore continuity of the GI tract (Tierney et al., 2000). The type of surgery recommended depends on the location and size of the tumor. Cancers limited to one site can be removed through the colonoscope. Laparoscopic colotomy with polypec-tomy minimizes the extent of surgery needed in some cases. A lap-aroscope is used as a guide in making an incision into the colon; the tumor mass is then excised. Use of the neodymium/yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd:YAG) laser has proved effective with some lesions as well. Bowel resection is indicated for most class A lesions and all class B and C lesions. Surgery is sometimes recommended for class D colon cancer, but the goal of surgery in this instance is palliative; if the tumor has spread and involves surrounding vital structures, it is considered nonresectable.

Surgical

procedures include the following:

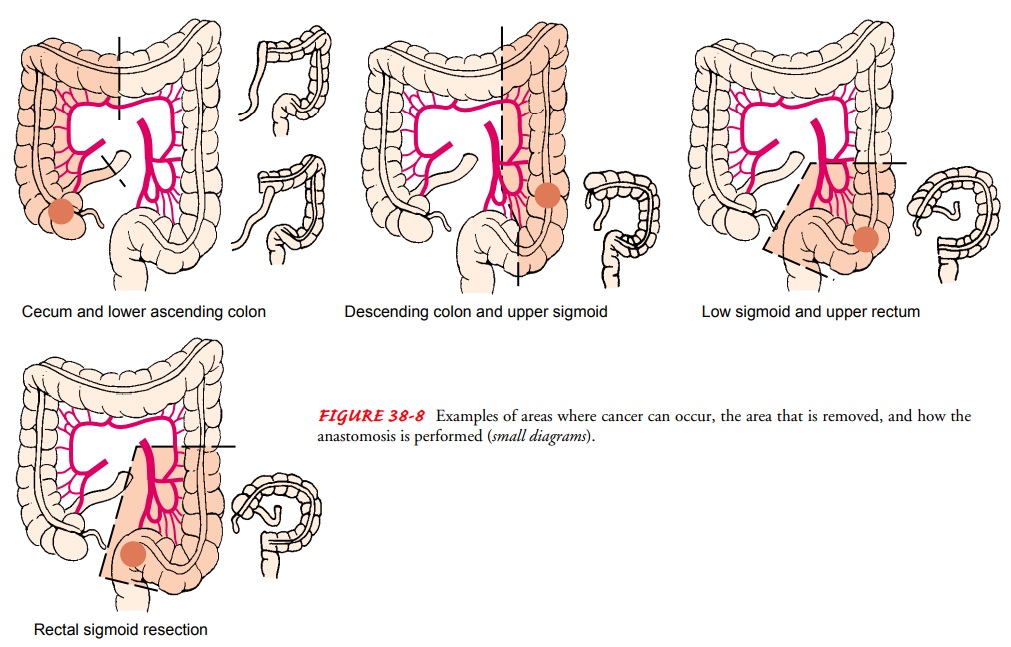

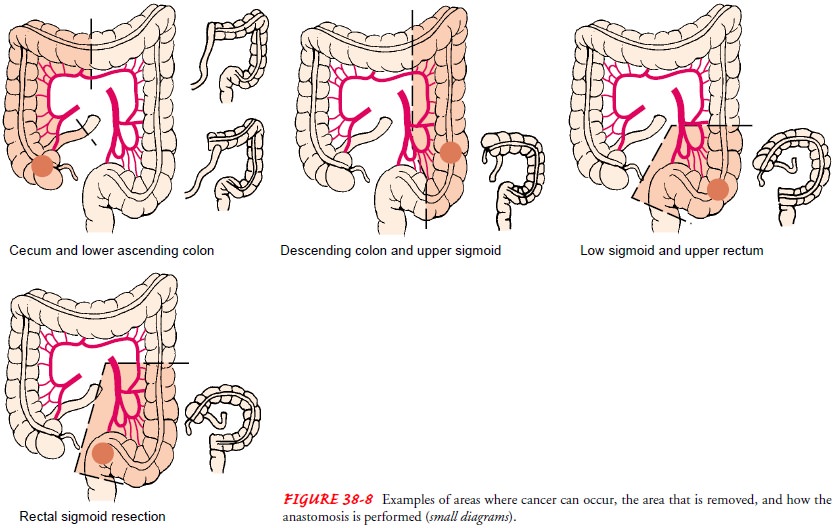

•

Segmental resection with anastomosis (ie, removal

of the tumor and portions of the bowel on either side of the growth, as well as

the blood vessels and lymphatic nodes) (Fig. 38-8).

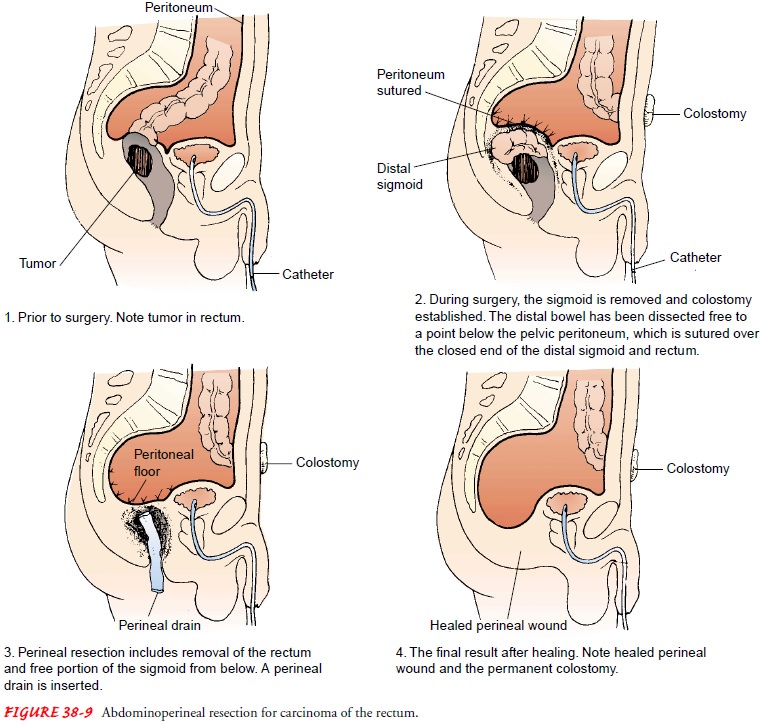

•

Abdominoperineal resection with permanent sigmoid

colos-tomy (ie, removal of the tumor and a portion of the sigmoid and all of

the rectum and anal sphincter) (Fig. 38-9).

•

Temporary colostomy followed by segmental resection

and anastomosis and subsequent reanastomosis of the colostomy, allowing initial

bowel decompression and bowel preparation before resection

•

Permanent colostomy or ileostomy for palliation of

unre-sectable obstructing lesions

•

Construction of a coloanal reservoir called a

colonic J pouch is performed in two steps. A temporary loop ileostomy is

constructed to divert intestinal flow, and the newly con-structed J pouch (made

from 6 to 10 cm of colon) is re-attached to the anal stump. About 3 months

after the initial stage, the ileostomy is reversed, and intestinal continuity

is restored. The anal sphincter and therefore continence are preserved.

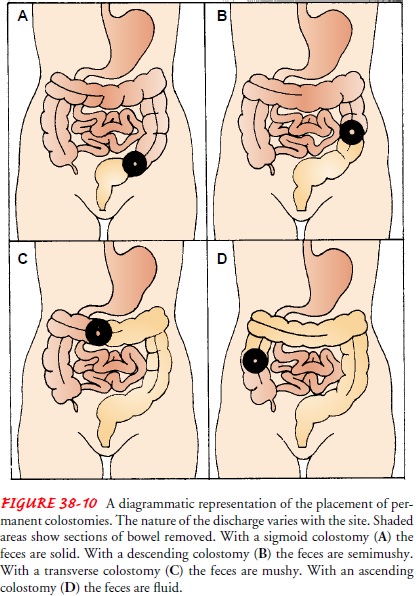

A colostomy is the surgical creation of

an opening (ie, stoma) into the colon. It can be created as a temporary or

permanent fecal diversion. It allows the drainage or evacuation of colon

con-tents to the outside of the body. The consistency of the drainage is

related to the placement of the colostomy, which is dictated by the location of

the tumor and the extent of invasion into sur-rounding tissues (Fig. 38-10).

With improved surgical tech-niques, colostomies are performed on fewer than one

third of patients with colorectal cancer.

Gerontologic Considerations

The

elderly are at increased risk for complications after surgery and may have

difficulty managing colostomy care. They may have decreased vision, impaired

hearing, and difficulty with fine motor coordination. It may be helpful for the

patient to handle ostomy equipment and simulate cleaning the peristomal skin

and irri-gating the stoma before surgery. Skin care is a major concern in the

elderly ostomate because of the skin changes that occur with aging—the epithelial

and subcutaneous fatty layers become thin, and the skin is irritated easily. To

prevent skin breakdown, special attention is paid to skin cleansing and the

proper fit of an appliance. Arteriosclerosis causes decreased blood flow to the

wound and stoma site. As a result, transport of nutrients is de-layed, and

healing time may be prolonged. Some patients have delayed elimination after

irrigation because of decreased peristalsis and mucus production. Most patients

require 6 months before they feel comfortable with their ostomy care.

Related Topics