Chapter: Biochemistry: Nucleic Acid Biotechnology

What is cloning?

What is cloning?

The term

clone refers to a genetically

identical population, whether of organisms, cells, viruses, or DNA molecules.

Every member of the population is derived from a single cell, virus, or DNA

molecule. It is particularly easy to see how individual bacteriophages and

bacterial cells can produce large numbers of progeny. Bacteria grow rapidly,

and large populations can be obtained relatively easily under laboratory

conditions. Viruses also grow easily. We shall examine each of these examples

in turn.

A virus

can be considered a genome with a protein coat, usually consisting of many

copies of one kind of protein or, at most, a small number of different kinds of

proteins. The viral genome can be double-stranded or single-stranded DNA or

RNA. For purposes of this discussion, we confine our attention to DNA viruses

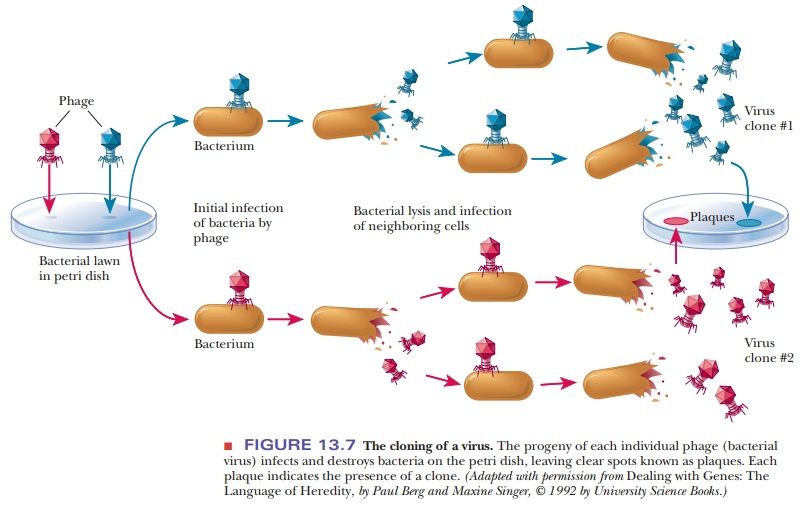

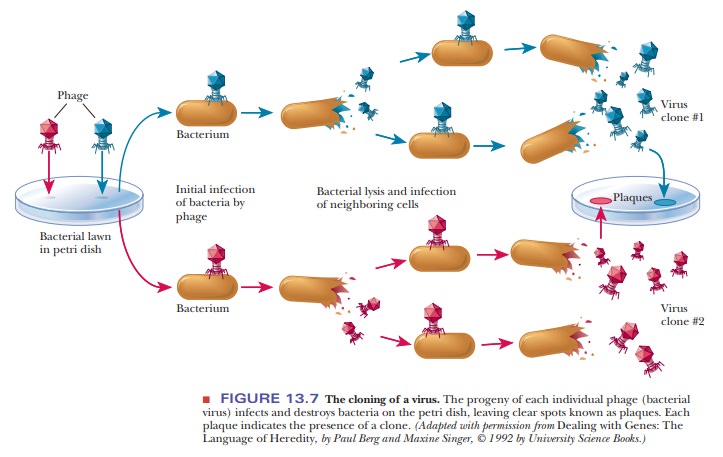

with double-stranded DNA. In the cloning of bacteriophages, a “lawn” of

bacteria covering a petri dish is infected with the phage. Each individual

virus infects a bacterial cell and reproduces, as do its progeny when they

infect and destroy other bacterial cells. As the virus multiplies, a clear

spot, called a plaque, appears on the

petri dish, marking the area in which the bacterial cellshave been killed

(Figure 13.7). The plaque consists of the progeny viruses that are clones of

the original.

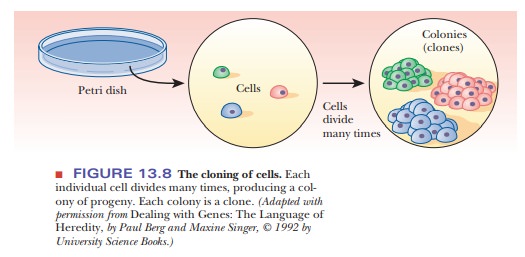

To clone

individual cells, whether from a bacterial or a eukaryotic source, a small

number of cells is spread thinly over a suitable growth medium in a dish.

Spreading the cells thinly ensures that each cell will multiply in isolation

from the others. Each colony of cells that appears on the dish will then be a

clone derived from a single cell (Figure 13.8). Because large quantities of

bacteria and bacte-riophages can be grown in short time intervals under

laboratory conditions, it is useful to introduce DNA from a larger,

slower-growing organism into bacteria or phages and to produce more of the

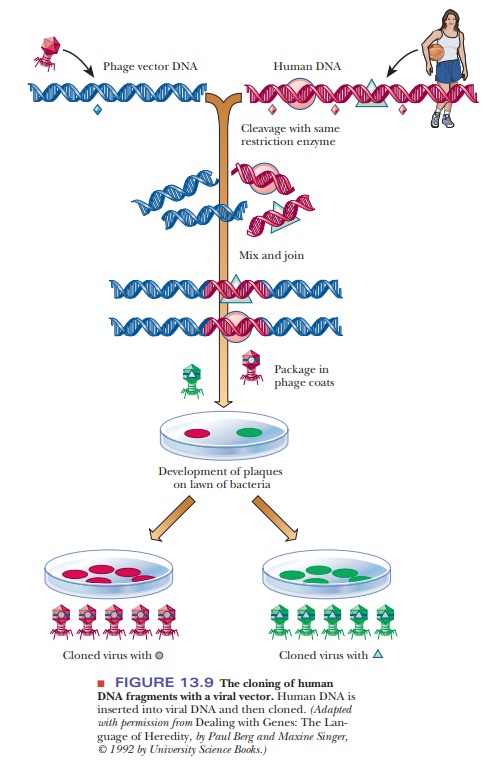

desired DNA by cloning. If, for example, we want to take a portion of human

DNA, which would be hard to acquire, and clone it in a virus, we can treat the

human DNA and the virus DNA with the same restriction endonuclease, mix the

two, and allow the sticky ends to anneal. If we then treat the mixture with DNA

ligase, we have produced recombinant DNA. To clone it, we incorporate the

chimeric DNA into virus particles by adding viral coat protein and allowing the

virus to assemble itself. The virus particles are spread on a lawn of bacteria,

and the cloned segments in each plaque can then be identi-fied (Figure 13.9).

The bacteriophage is called a vector,

the carrier for the gene of interest that was cloned. The gene of interest is

called many things, such as the “foreign

DNA,” the “insert,” “geneX,” or

even “YFG,” for “your favorite gene.”

Related Topics