Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Regional Anesthesia & Pain Management: Peripheral Nerve Blocks

Upper Extremity Peripheral Nerve Blocks: Interscalene Block

Interscalene Block

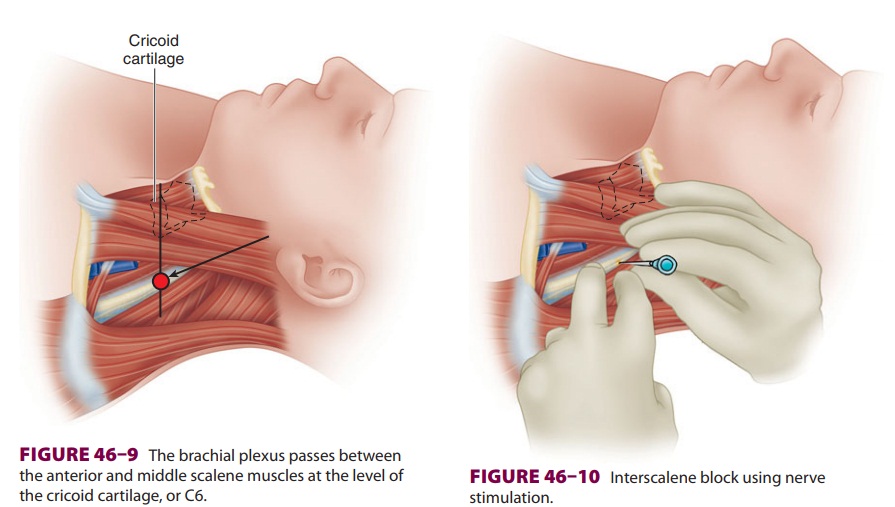

An interscalene brachial plexus block is

indicated for procedures involving the shoulder and upper arm (Figure

46–8). Roots C5–7 are most densely blocked with

this approach; and the ulnar nerve originating from C8 and T1 may be spared.

There-fore, interscalene blocks are not appropriate for sur-gery at or distal to

the elbow. For complete surgical anesthesia of the shoulder, the C3 and C4

cutane-ous branches may need to be supplemented with a superficial cervical

plexus block or local infiltration.Contraindications to an interscalene block

include local infection, severe coagulopathy, local anesthetic

allergy, and patient refusal. A properly

performed interscalene block invariably blocks the ipsilateral phrenic nerve

(completely for nerve stimulation techniques; unclear for ultra-sound-guided

techniques), so careful consideration should be given to patients with severe

pulmonary disease or preexisting contralateral phrenic nerve palsy. The

hemidiaphragmatic paresis may result in

dyspnea, hypercapnia, and hypoxemia. A Horner’s syndrome (myosis,

ptosis, and anhidrosis) may result from proximal tracking of local anesthetic

and blockade of sympathetic fibers to the cervico-thoracic ganglion. Recurrent

laryngeal nerve involvement often induces hoarseness. In a patient with contralateral

vocal cord paralysis, respiratory distress may ensue. Other site-specific risks

include vertebral artery injection (suspect if immediate sei-zure activity is

observed), spinal or epidural injec-tion, and pneumothorax. Even 1 mL of local

anesthetic delivered into the vertebral artery may induce a seizure. Similarly,

intrathecal, subdural, and epidural local anesthetic spread is possible.Lastly,

pneumothorax is possible due to the close proximity of the pleura.

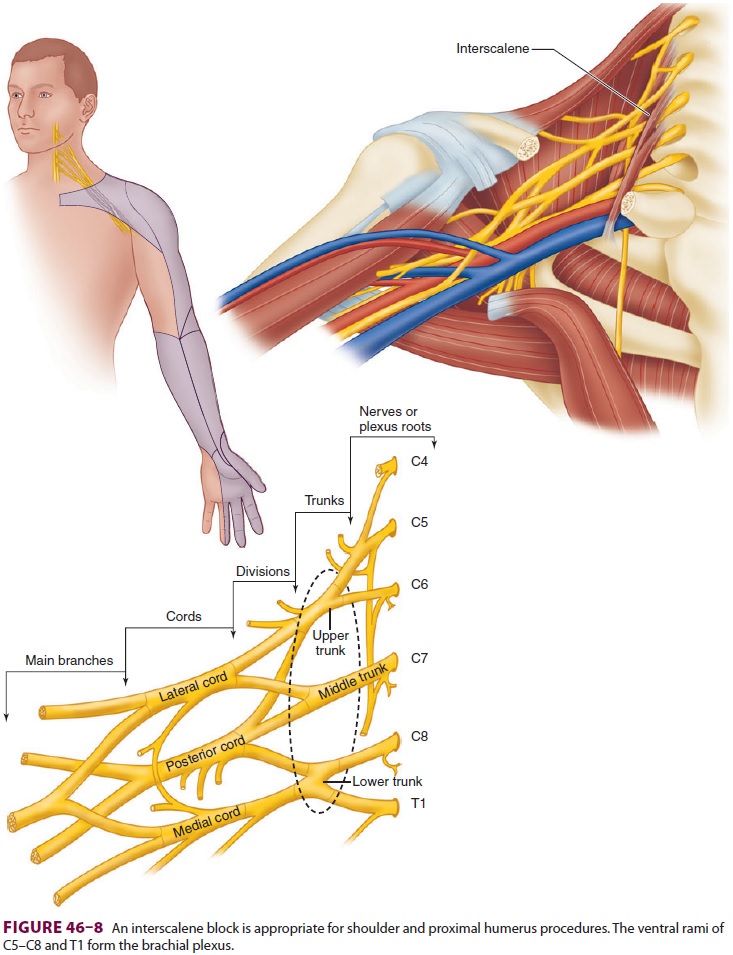

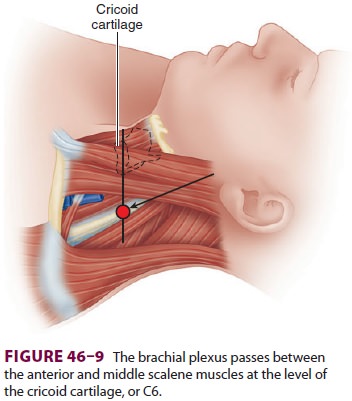

The brachial plexus passes between the anterior

and middle scalene muscles at the level of the cricoid cartilage, or C6 ( Figure

46–9). Palpation of the inter-scalene groove is

usually accomplished with the patient supine and the head rotated 30° or less

to the contralateral side. The external jugular vein often crosses the

interscalene groove at the level of the cricoid cartilage. The interscalene

groove should not be confused with the groove between the sternoclei-domastoid

and the anterior scalene muscle, which lies further anterior. Having the

patient lift and turn the head against resistance often helps delineate the

anatomy. If surgical anesthesia is desired

for the entire shoulder, the intercostobrachial nerve must usually be targeted

separately with a field block since it originates from T2 and is not affected

with an interscalene block. Interscalene perineural infusions provide potent

analgesia following shoulder surgery.

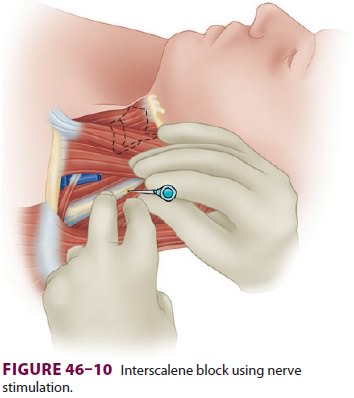

A. Nerve Stimulation

relatively short (5-cm) insulated needle is

usu-ally employed. The interscalene groove is palpated using the nondominant

hand, pressing firmly to stabilize the skin against the underlying structures (Figure

46–10). After the skin is anesthetized, the block

needle is inserted at a slightly medial and cau-dad angle and advanced to

optimally elicit a motor response of the deltoid or biceps muscles (suggesting

stimulation of the superior trunk). A motor response of the diaphragm indicates

that the needle is placed in too anterior a direction; a motor response of the

trapezius or serratus anterior muscles indicates that the needle is placed in

too posterior a direction. If bone (transverse process) is contacted, the

needle should be redirected more anteriorly. Aspiration of arterial blood

should raise concern for vertebral or carotid artery puncture; the needle

should be

withdrawn, pressure held for 3–5 min, and land-marks reassessed.

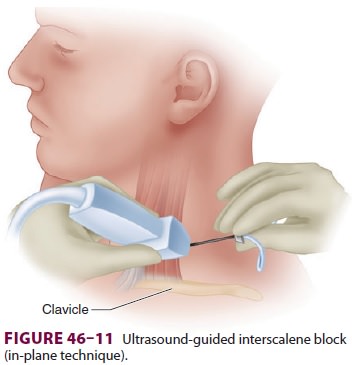

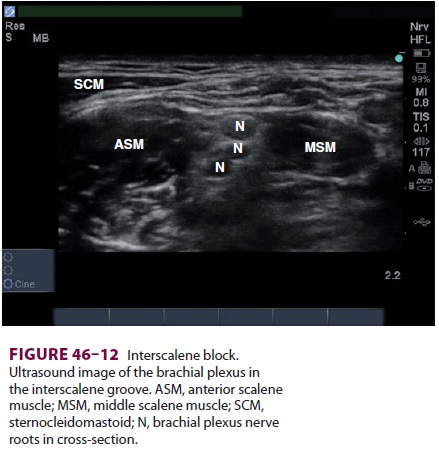

B. Ultrasound

A needle in-plane or out-of-plane technique

may be used, and an insulated needle attached to a nerve stimulator can be used

to confirm the accuracy of the targeted structure. For both techniques, after

identification of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and interscalene groove at the

approximate level of C6, a high-frequency linear transducer is placed

perpendicular to the course of the interscalene mus-cles (short axis; Figure

46–11). The brachial plexus and anterior and

middle scalene muscles should be visualized in cross-section (Figure

46–12). The brachial plexus at this level appears

as three to five hypoechoic circles. The carotid artery and internal jugular

vein may be seen lying anterior to the ante-rior scalene muscle; the

sternocleidomastoid is vis-ible superficially as it tapers to form its lateral

edge.

For an out-of-plane technique, the block nee-dle is inserted just

cephalad to the transducer and advanced in a caudal direction toward the

visual-ized plexus. After careful aspiration for nonappear-ance of blood, local

anesthetic (hypoechoic) spread

should occur adjacent to (sometimes surrounding) the plexus.

For an in-plane technique, the needle is

inserted just posterior to the ultrasound transducer in a direc-tion exactly

parallel to the ultrasound beam. A lon-ger block needle (8 cm) is usually

necessary. It may be helpful to have the patient turn slightly laterally with

the affected side up to facilitate manipulation of the needle. The needle is

advanced through the middle scalene muscle until it has passed through the

fascia anteriorly into the interscalene groove. The needle tip and shaft should

be visualized during the entire block performance. Depending on visu-alized

spread relative to the target nerve(s), a lower volume (10 mL) may be employed

for postoperative analgesia, whereas a larger volume (20–30 mL) is commonly

used for surgical anesthesia.

Related Topics