Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Regional Anesthesia & Pain Management: Peripheral Nerve Blocks

Upper Extremity Peripheral Nerve Blocks: Axillary Block

Axillary Block

At the lateral border of the pectoralis minor

muscle, the cords of the brachial plexus form large terminalbranches.

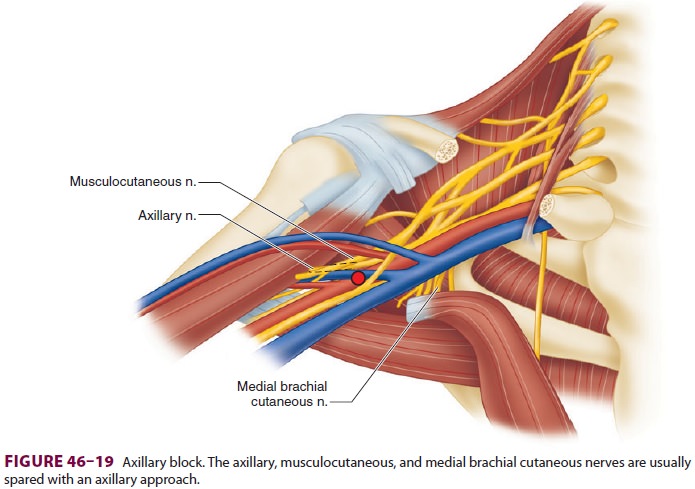

The axillary, musculocutaneous, and medial brachial cutaneous nerves branchfrom the

brachial plexus proximal to the location in which local anesthetic is deposited

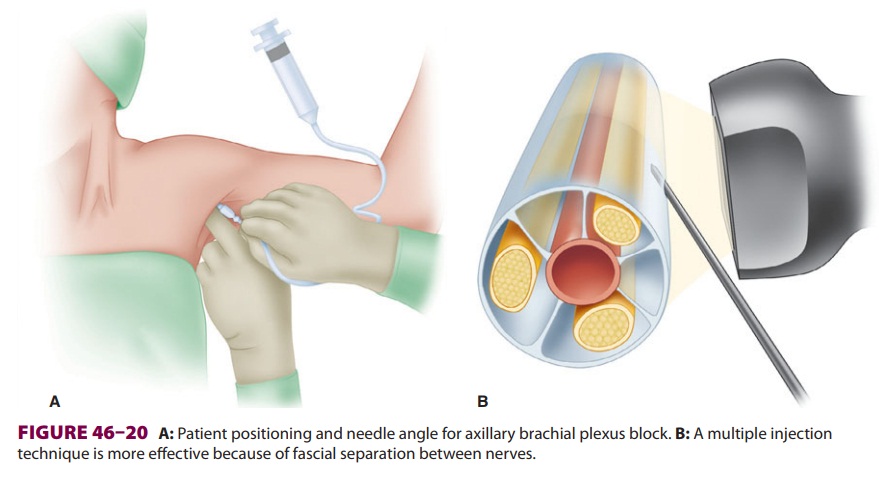

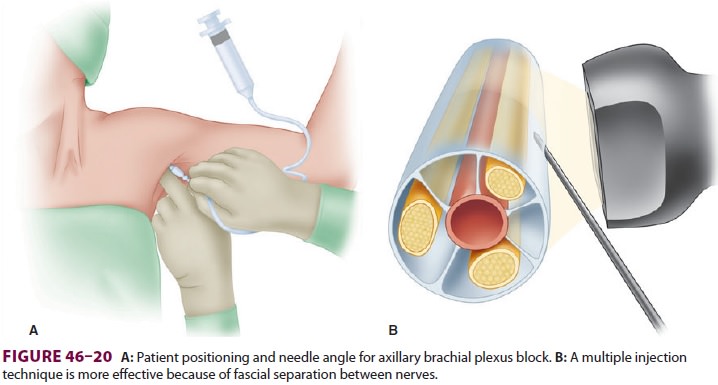

during an axil-lary nerve block, and thus are usually spared (Figure

46–19). At this level, the major terminal nerves often are separated by

fascia; therefore mul-tiple injections (10-mL each) may be required to reliably

produce anesthesia of the entire arm distal to the elbow (Figure

46–20).

There are few contraindications to axillary

bra-chial plexus blocks. Local infection, neuropathy, and bleeding risk must be

considered. Because the axilla is highly vascularized, there is a risk of local

anes-thetic uptake through small veins traumatized by needle placement. The

axilla is also a suboptimal site for perineural catheter placement because of

greatly inferior analgesia versus an infraclavicular infusion, as well as

theoretically increased risks of infection and catheter dislodgement.

All of the numerous axillary block techniques

require the patient to be positioned supine, with the arm abducted 90 o and the head turned toward the contralateral

side (Figure 46–20). The axillary artery pulse should be palpated and its

location marked as a reference point.

A. Transarterial Technique

This technique has fallen out of favor due to the trauma of twice

purposefully penetrating the axil-lary artery along with a theoretically

increased risk of inadvertent intravascular local anesthetic injec-tion. The

nondominant hand is used to palpate and immobilize the axillary artery, and a

22-gauge needle is inserted high in the axilla (Figure 46–20) until bright red blood

is aspirated. The needle is then slightly advanced until blood aspiration

ceases. Injection can be performed posteriorly, anteriorly, or in both

locations in relation to the artery. A total of 30–40 mL of local anesthetic is

typically used.

B. Nerve Stimulation

Again the nondominant hand is used to palpate

and immobilize the axillary artery. With the arm abducted and externally

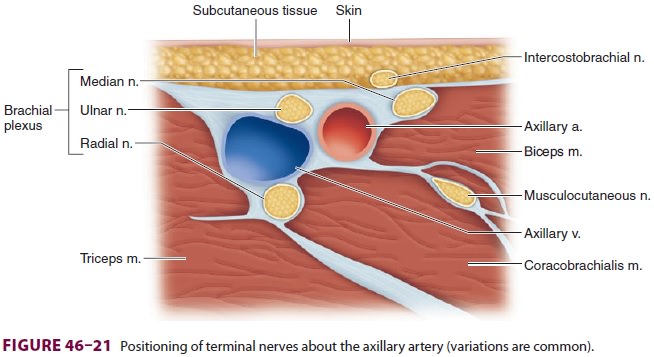

rotated, the terminal nerves usually lie in the following positions relative to

the artery (Figure 46–21, although variations

are common): median nerve superior (wrist flexion, thumb opposition, forearm

pronation); ulnar nerve inferior (wrist flexion, thumb adduction, fourth/ fifth

digit flexion); and radial nerve inferior–poste-rior (digit/wrist/elbow

extension, forearm supina-tion). The musculocutaneous nerve (elbow flexion) is

separate and deep within the coracobrachialis muscle, which is more superior

(lateral) in this posi-tion and, as a consequence, is often not blocked with

this procedure (Figure 46–21). A 2-in., 22-gauge insulated needle is inserted

proximal to the palpat-ing fingers to elicit muscle twitches in the hand. Once

an acceptable muscle response is identified, and after reducing the stimulation

to less than 0.5 mA, careful aspiration is performed and local anes-thetic is

injected. Although a single injection of 40 mL may be used, greater success

will be seen with multiple nerve stimulations (ie, two or three nerves) and

divided doses of local anesthetic.

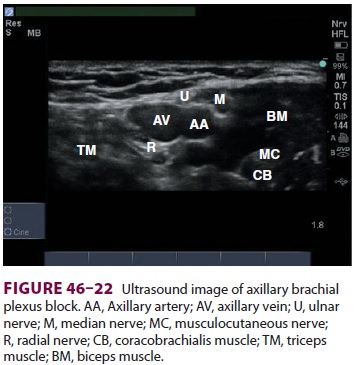

C. Ultrasound

Using a high-frequency linear array

ultrasound transducer, the axillary artery and vein are visual-ized in

cross-section. The brachial plexus can be identified surrounding the artery (Figure

46–22). The needle is inserted superior (lateral)

to the trans-ducer and advanced inferiorly (medially) toward the plexus under

direct visualization. Ten milliliters of local anesthetic is then injected

around each nerve (including the musculocutaneous, if indicated).

Related Topics