Chapter: Psychology: Development

The Role of Culture - Socioemotional Development in Infancy and Childhood

THE ROLE

OF

CULTURE

Another

source of differences among children comes from the cultural context within

which the child

develops. Some cultural influences

on development are

obvious. In ancient Rome, for example, educated children learned to

represent num-bers with Roman numerals; modern children in the West, in

contrast, learn to represent numbers with Arabic numerals. Modern children in

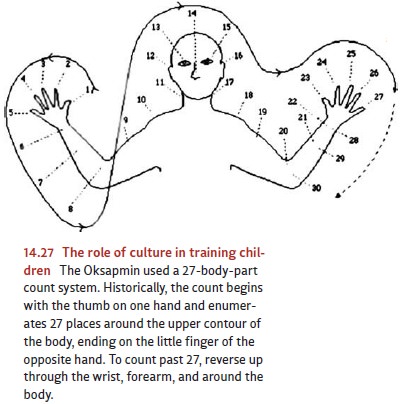

the Oksapmin culture (in New Guinea) learn yet a different system, counting

using parts of the body rather than numbers (Figure 14.27; Saxe, 1981). In each

case, this culturally provided tool guides (and in some cases,

limits) how the

children think about

and work with numerical quantities.

In

addition, some social and cultural settings involve formal schooling, but

others do not, and schooling is a powerful influence on the child’s development

(Christian, Bachman, & Morrison, 2000; Rogoff et al., 2003). Cultures also

differ in what activities children are exposed to, how frequently these

activities occur, and what the chil-dren’s

role is in the activity. These factors

play an important

part in determining

what skills—intellectual and motor—the children will gain and the level

of skill they will attain (M. Cole & Cole, 2001; Laboratory of Comparative

Human Cognition, 1983; Rogoff, 1998, 2000).

In

understanding these various cultural influences, though, it is crucial to bear

in mind that the child is not a passive recipient of social and cultural input.

Instead, the child plays a key role in selecting and shaping her social

interactions in ways that, in turn, have a powerful effect on how and what she

learns.

Part

of the child’s role in selecting and shaping her social interactions is defined

by what Lev Vygotsky (1978) called the zone

of proximal development. This term refers to the range of accomplishments

that are beyond what the child could do on her own, but that are possible if

the child is given help or guidance. Attentive caregivers or teach-ers

structure their input to keep the child’s performance within this zone—so that

the child is challenged, but not overwhelmed, by the task’s demands.

Importantly, the child herself provides feedback to those around her that helps

maintain this level of guid-ance. Thus, caregivers are able to monitor the

child’s progress and, in some cases, the child’s frustration level, as a

project proceeds, and they can then adjust accordingly how much help they

offer.

The

child also plays an active role whenever the processes of learning or problem

solving involve the shared efforts of two or more people (after Rogoff, 1998).

In such cases, it is clear that we cannot understand development if we focus

either on the child or on the social context; instead, we must understand the

interaction of the two and how each shapes the other.

One

example of this interplay is seen in the child’s capacity for remembering life

events. This capacity might seem to depend entirely on processes and resources

inside the individual, with little room for social influence. Evidence

suggests, however, that the capacity for remembering events grows in part out

of conversations in which adults help children to report on experiences. When

the child is quite young, these conversa-tions tend to be one-sided. The parent

does most of the work of describing the remem-bered event and gets little input

from the child. (“Remember when we went to see Grandma, and she gave you a

teddy bear?”) As the child’s capacities grow, the parent retreats to a narrower

role, first asking specific questions to guide the child’s report (“Did you see

any elephants at the zoo?”), then, at a later age, asking only broader

questions (“What happened in school today?”), and eventually listening as the

child reports on some earlier episode. Over the course of this process, the

parent’s specific questions, the sequence of questions, and their level of

detail all guide the child as he figures out what is worth reporting in an

event and, for that matter, what is worth pay-ing attention to while the event

is unfolding (Fivush, 1998; Fivush & Nelson, 2004; K. Nelson & Fivush,

2000; Peterson & McCabe, 1994).

Of

course, parents talk to their children in different ways. Some parents tend to

elaborate on what their children have said; some simply repeat the child’s

comments (Reese & Fivush, 1993). For example, Mexican Americans and

Anglo-Americans differ in how they converse with their children and in what

they converse about, with Mexican Americans’ emotion talk tending to be less

explanatory than Anglo-Americans’. There are also differences in adult-child

conversations if we compare work-ing-class and middle-class parents (see, for

example, A. R. Eisenberg, 1999).

In

each case, these differences in conversational pattern have an impact on how

the child structures his or her memory. As one example, evidence suggests that

American mothers talk with their children about past events much more than

Asian mothers do (Mullen & Yi, 1995). These conversations may help American

children to start organiz-ing their autobiographical recall at an earlier age

than Asian children. Consistent with this suggestion, when Caucasian adults are

asked to report their earliest childhood memories, they tend to remember events

earlier in life than do Asian adults (Fivush & Haden, 2003; Mullen, 1994).

The same logic may help explain why women tend to remember events from earlier

in their lives than men do. This difference in memory may result from

differences in the way parents converse with their sons and daughters (Fivush

& Haden, 2003; Fivush & Nelson, 2004).

Related Topics