Chapter: Psychology: Development

Cognitive Changes in Adulthood

Cognitive Changes in Adulthood

Life

expectancies have increased dramatically. In the years of the Roman Empire,

people lived only two or three decades; early in the twentieth century, death

by age 40 was common. By 1955, worldwide life expectancy had reached 48 years;

the world aver-age was 68 in 1998 and is far beyond that today in many

countries (WHO, 1998). These demographic changes mean that a larger proportion

of the world’s population is old than ever before, and this has encouraged a

growing interest in the nature of age-related changes in cognitive functioning,

as well as the steps that can be taken to halt or even reverse the decline

associated with aging. A number of encouraging early studies have suggested

predictors of “successful aging” and other studies have offered mental training

programs or strategies that can help people retain and improve their cognitive

abilities (Baltes, Staudinger, & Lindenberger, 1999; Freund & Baltes,

1998; Hertzog, Kramer, Wilson, & Lindenberger, 2009). To appreciate this

work, we need to consider how cognitive performance changes with age.

CHANGES IN INTELLECTUAL PE RFORMANCE

Failing

memory has long been considered an unavoidable part of aging. However, some

aspects of memory—including implicit memory and some measures of semantic

memory—show little or no decline with aging. Age-related declines are evident,

however, in measures of working memory and episodic memory (see, for example,

Earles, Connor, Smith, & Park, 1998). The elderly also have trouble in accessing their memories; in fact, one

of the most common complaints associated with aging is the difficulty in

recalling names or specific words (G. Cohen & Burke, 1993).

The

broader decline in intellectual functioning is similarly uneven—the key

difference is between fluid and crystallized intelligence. As noted, fluidintelligence refers to a person’s

ability to deal with new and unusual problems, whereas crystallized intelligence refers to a person’s accumulated

knowledge, including his vocab-ulary, the facts he knows, and the strategies he

has learned.

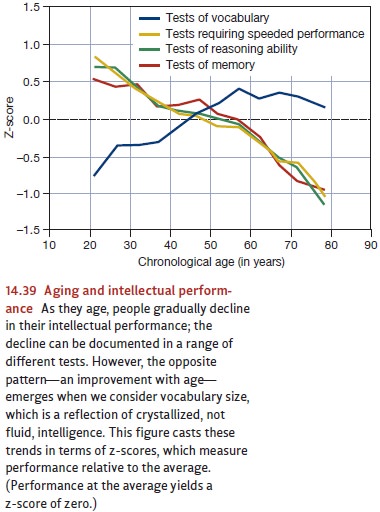

Crystallized

intelligence remains relatively stable across the life span and, in some

stud-ies, seems to grow as the individual gains life experience. Fluid

intelligence shows a very dif-ferent pattern. The decline starts when the

person is in his twenties and continues as the years go by (Figure 14.39).

However, the decline is gradual, and many individuals maintain much of their

intellectual capacity into their sixties and seventies (Craik & Salthouse,

2000; Salthouse, 2000, 2004; Schaie, 1996; Verhaeghen & Salthouse, 1997).

Figure

14.39 suggests that the decline in mental capacities proceeds steadily across

much of the life span. Why, therefore, do we notice the decline primarily in

the elderly? Why do people often lament the loss of cognitive capacities

between ages 60 and 80, but not comment on the similar drop-off between ages 20

and 40? One reason is that as one

matures, gains in crystallized

intelligence often compensate

for declines in fluid intelligence. Thus, as the years pass, people

master more and more strategies that help them in their daily functioning, and

this balances out the fact that their thinking is not as nimble as it used to

be. In addition, 30- or 40-year-olds might be less able than 20-year-olds, but

we do not detect the decline because the 30- or 40- year-olds still have more

than adequate capacity to manage their daily routines. We

detect cognitive decline

only later, when

the gradual drop-off in

mental skills eventually

leaves people with

insufficient capacity to handle their daily chores (Salthouse, 2004).

Common sense also

suggests that people

differ markedly in

how they age—some show a dramatic drop in mental

capacities but others experience very little loss. This may be an instance in

which common sense doesn’t match the facts. If we focus on individu- als who

are still reasonably

active and who

describe themselves as

being in “good

to

excellent

health,” then we find impressive consistency from one individual to the next in

how they are affected by the passing years (Salthouse, 2004). Put differently,

the drop- off we see in Figure 14.39 is not the result of a few unfortunate

individuals who rapidly lose their abilities and pull down the average.

Instead, the decline seems to affect most people, to roughly the same degree.

CAUSES OF AGE - RELATED DECLINES INCOGNITIVE FUNCTIONING

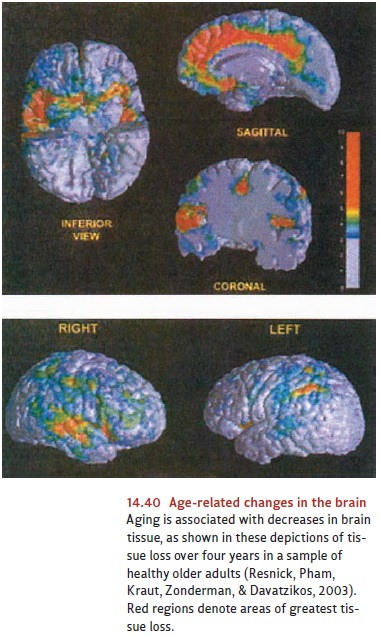

What

factors are responsible for age-related cognitive declines? Some investigators

pro- pose biological explanations, cast in terms of age-related changes in

blood flow or neu- roanatomy, or the gradual death of neurons across the life

span (Figure 14.40; Resnick et al., 2003).

Still others have

suggested that the

cause of many

of these cognitive changes is an age-related decline

in working memory or the capacity for paying atten- tion (Craik &

Bialystok, 2006). In fact, all of these hypotheses may be correct, and each may

describe one of the factors that governs how individuals age.

The

way each individual ages is also shaped by other factors. One factor is the

degree of stimulation in the individual’s life (Schaie & Willis, 1996);

those who are less stim- ulated are more vulnerable to the effects of aging. Also relevant are a wide variety of

medical factors. This reflects the fact that the cells making up the central

nervous sys- tem can function only if they receive an ample supply of oxygen

and glucose. (In fact, the brain consumes

almost 20% of

the body’s metabolic

energy, even though

it accounts for only about 2 or 3% of the overall body weight.) As a

result, a wide range of bodily changes that diminish the availability of these

resources can also impair brain functioning. For example, a decline in kidney

function will have an impact throughout the body, but because of the brain’s

metabolic needs, the kidney problem may lead to a loss in

mental functioning well

before other symptoms

appear. Likewise, circulatory problems (including problems with the

heart itself or hardening of the arteries) will obviously diminish the

quantity and quality of the brain’s blood supply, and so can con- tribute to a

cognitive decline (see, for example, Albert et al., 1995).

Finally, cognitive

functioning in the

elderly is also

affected by a

number of age- related diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, a disorder

characterized by a progres- sive and widespread loss of nerve cells, leading to

memory problems, disorientation, and, eventually, total helplessness. Evidence

has made it clear that genetic factors can increase someone’s risk of

Alzheimer’s disease (Goedert & Spillantini, 2006), but its exact causes

remain uncertain.

These

declines may sound downright discouraging, because they highlight the many

fronts on which we are all vulnerable to aging, but there are ways to slow the

process. For example, physical exercise has been shown to be good for not only

the body (maintaining muscle strength and tone, as well as cardiovascular

fitness) but also the mind. Although fitness programs are not a cure-all for

the effects of aging, physical exercise can, in many cases, help preserve

mental functioning in the elderly (Colcombe & Kramer, 2003; Cotman &

Neeper, 1996; A. F. Kramer & Willis, 2002). There is also a growing

literature on the effi-cacy of mental

exercise, although the jury is still out on the extent and breadth of gains

associated with mental exercise (Salthouse, 2006, 2007; Schooler, 2007).

Related Topics