Chapter: Psychology: Development

Socioemotional Development in Adolescence

Socioemotional Development in Adolescence

The

physical changes in adolescence are easily visible as young teens undergo a

whole-sale remodeling of their bodies. Even more obvious are the changes in the

adolescent’s social and emotional world as the adolescent asserts a new

independence, his focus shifts from family to friends, and he copes with a wide

range of new social, romantic, and sexual experiences.

The

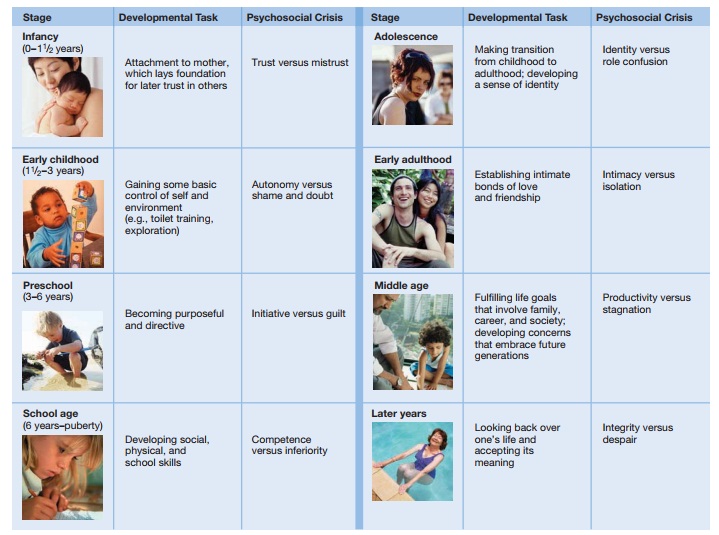

psychoanalyst Erik Erikson provided one influential framework for thinking

about these and other major life changes in his “eight ages of man” (Figure

14.35). According to Erikson (1963), all human beings endure a series of crises

as they go through the life cycle. At each stage, there is a critical

confrontation between the self the individual has achieved thus far and the

various social and personal demands relevant to that phase of life (Erikson

& Coles, 2000). The first few of these “crises” occur in early childhood.

However, a major new crisis arises in adolescence and lasts into early

adulthood. This crisis concerns self-identity, and Erikson referred to this

crisis as

identity versus role confusion.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF SELF - IDENTITY

One

of the major tasks of adolescence is determining who one is. As part of this

effort toward discovery, adolescents try on many different roles to see which

ones fit best—which vocation, which ideology, which ethnic group membership. In

many cases, this means trying on roles that will allow the adolescents to mark

the clear distinctions between them and their parents. If their parents prefer

safe behaviors, this will tempt the adolescents toward dangerous activities. If

their parents prefer slow-paced recre-ation, the adolescents will seek

excitement (J. R. Harris, 1995, 1998).

The crucial life task at this stage, in Erikson’s view, is integrating changes in one’s body, one’s intellectual capacities, and one’s role in a way that leads to a stable sense of ego identity, which Erikson defined as “a feeling of being at home in one’s body, a senseof ‘knowing where one is going,’ and an inner assuredness of anticipated recognition from those who count”. Developing an ego identity is difficult—and success is not guaranteed. Less satisfactory outcomes include identityconfusion, in which no stable identity emerges, or the emergence of a negative identity, based on undesirable roles in society, such as the identity of a delinquent.

RELATIONS WITH PARENTS AND PEERS

Traditionally,

adolescence has been considered a period of great emotional stress. In

adolescent years, children break away from parental control and seek to make

their own choices about their activities, diet, schedule, and more. At the same

time, adolescents are shifting the focus of their social worlds, so that they

spend more time with, and gain much more emotional support from, peers rather

than family members (Figure 14.36). These shifts allow adolescents to explore a

variety of newfound freedoms, including participating in activities away from

adult supervision—a prospect that is simultane-ously exciting and emotionally

stressful.

With

all of these changes, the stage seems to be set for tension between adolescents

and their parents, so it is no surprise that, across the centuries, literature

(and, more recently, film) has featured youths in desperate conflict with the

adult world. Perhaps surprisingly, a number of studies suggest that emotional

turbulence is by no means uni-versal among adolescents. There are conflicts, of

course, and the nature of the conflict changes over the course of adolescence

(Laursen, Coy, & Collins, 1998). But many inves-tigators find that even

though “storm and stress” is more likely during adolescence than at other

points (Arnett, 1999), for most adolescents “development . . . is slow,

gradual, and unremarkable”.

What

determines whether adolescence will be turbulent or not? Despite the grow-ing

importance of peers during this period, parenting styles continue to make a

clear difference. Evidence suggests that the adolescent children of

authoritative parents (who exercise their power, but respond to their

children’s opinions and reasonable requests) tend to be more cheerful, more

responsible, and more cooperative—both with adults and peers (Baumrind, 1967).

Teenagers raised by authoritative parents also seem more confident and socially

skilled (Baumrind, 1991). This parental pattern is also associated with better

grades and better SAT scores as well as better social adjustment (Dornbusch,

Ritter, Liederman, Roberts, & Fraleigh, 1987; Steinberg, Elkman, &

Mounts, 1989; L . H. Weiss & Schwarz, 1996). These are striking findings

and—impressively—are not limited to Western (individualistic) cultures.

Authoritative parenting is also associated with better adolescent outcomes in

collec-tivistic cultures (Sorkhabi, 2005; Steinberg, 2001).

No

matter what the parents’ style, adolescence poses serious challenges as young

adults prepare to become autonomous individuals. Sometimes the process does not

go well. Some adolescents engage in highly risky forms of recreation. Some end

up with unplanned (and undesired) pregnancies. Some commit crimes. Some become drug

users. Indeed, statistics show that all of these behaviors (including theft,

murder, reck-less driving, unprotected sex, and use of illegal drugs) are more

likely during adolescence than at any other time of life (Arnett, 1995, 1999),

although it bears emphasizing that only a minority of adolescents experience

serious negative outcomes.

Why

are risky and unhealthy behaviors more common among adolescents than among

other age groups? Several factors seem to contribute (Reyna & Farley,

2006). We have already mentioned one—the absence of a fully mature forebrain

may make it more difficult for adolescents to rein in their impulses. As a

further element, it seems in many settings that adolescents simply do not think

about, or take seriously, the dangers and potential consequences of their

behaviors, acting instead as if they are somehow invulnerable to harm or

disease (Elkind, 1978). Moreover, other evidence suggests that adolescents are

especially motivated to seek out new and exciting experiences, and this sensation seeking regularly exposes them

to risk (Arnett, 1995; Keating, 2004; Kuhn, 2006).

Hand

in hand with this relative willingness to take risks, adolescents seek more and

more to identify with their own generation. As a result, their actions are

increasingly influenced by their friends—especially since, in adolescence,

people care more and more about being accepted

by their friends (Bigelow & LaGaipa, 1975). They are also influenced by

other peers, including the circle of individuals they interact with every day

and the “crowd” they identify with—the “brains” or the “jocks” or the

“druggies” (B. Brown, Moray, & Kinney, 1994). And, of course, if their

friends engage in risky activi-ties, it is more likely that they will, too

(Berndt & Keefe, 1995; Reed & Roundtree, 1997).

We

need to be careful, though, not to overstate the problems caused by peer

influence. In fact, most teenagers report that their friends are more likely to

discourage bad behav-iors than to encourage them (B. Brown, Clasen, &

Eicher, 1986). More generally, most peer influence is aimed at neither good

behaviors nor bad ones, but behaviors that are simply different from those of the previous generation, like styles of

clothing, hair styles, and slang that adolescents adopt (B. B. Brown, 1990;

Dunphy, 1963). Of course, these styles change quickly. As they diffuse rapidly

into the broader social world and in some cases become adult fashions, new

trends spring up to maintain the differentiation.

Related Topics