Chapter: Psychology: Development

Social Cognition and Theory of Mind

SOCIAL COGNITION AND THEORY OF MIND

The

social world provides yet another domain in which young children are

surpris-ingly competent (Striano & Reid, 2006). For example, infants seem

to have some understanding of other people’s intentions. Specifically, they understand the world they observe in

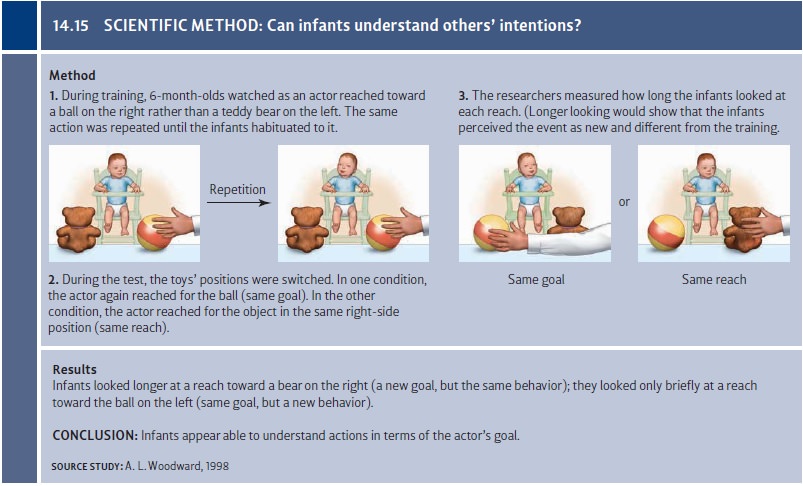

terms of others’ goals, and not just their movements. In one study, 6-month-old

infants saw an actor reach for a ball that was sitting just to the right of a

teddy bear. (The left–right position of the toys was reversed for half of the

infants tested.) The infant watched this event over and over, until he became

bored with it. At that point, the position of the toys was switched, so now the

teddy bear was on the right. Then the infant was shown one of two test events.

In one, the actor again reached for the ball (although, given the switch in position,

this was the first time the infant had seen a reach toward the left). In the

other condition, the actor again reached for the object on the right (although,

given the switch, this was the first time the infant had seen a reach toward

the teddy bear).

If,

in the initial observation, the infant was focusing on behavior (“reach

right”), then the reach-for-ball test event involves a change, and so will be a

surprise. If, however, the infant was focusing on the goal (“reach for ball”),

then it is the reach for the teddy bear that involves a change, and will be a

surprise. And, in fact, the latter is what the data show: Six-month-olds are

more surprised by the change in goal than by the change in behavior (A. L.

Woodward, 1998; Figure 14.15). Apparently, and contrary to Piaget, they

understand that the object reached for is separate from the reach itself, and

they are sophisticated enough in their perceptions that they understand others’

actions in terms of intended goals (see also Brandone & Wellman, 2009; Luo

& Baillargeon, 2005; Surian, Caldi, & Sperber, 2007; Woodward, 2009).

This

emerging understanding of others’ intentions is important, because it allows

the young child to make sense of, and in many cases predict, how others will

behave. However, understanding intentions is just one aspect of the young

child’s developing theory of mind—the

set of beliefs that someone employs whenever she tries to makesense of her own

behavior or that of others (Leslie, 1992; D. Premack & Woodruff, 1978;

H.

M. Wellman, 1990). The theory of mind also involves preferences—and the young child must come to understand that people

vary in their preferences and that people tend to make choices in accord with

their preferences. Here, too, we see early competence: In one study,

18-month-olds watched as experimenters made “yuck” faces after tasting one food

and smiled broadly after tasting another. The experimenters then made a general

request to these toddlers for food, and the children responded

appropriately—offering the food that the experimenter preferred, even if the

children themselves preferred the other food (Repacholi & Gopnik, 1997;

Rieffe, Terwogt, Koops, Stegge, & Oomen, 2001; for more on the child’s

theory of mind, see A. Gopnik & Meltzoff, 1997).

Yet

another aspect of the theory of mind involves beliefs. Suppose you tell 3-year-old Susie that Johnny wants to

play with his puppy. You also tell her that Johnny thinks the puppy is under

the piano. If Susie is now asked where Johnny will look, she will sensi-bly say

that he will look under the piano (H. M. Wellman & Bartsch, 1988). Like an

adult, a 3-year-old understands that a person’s actions depend not just on what

he sees and desires, but also on what he believes.

Let’s

be careful, though, not to overstate young children’s competence. If asked, for

example, what color an object is, 3-year-olds claim that they can find out just

as easily by touching an object as they can by looking at it (O’Neill,

Astington, & Flavell, 1992). Likewise, 4-year-olds will confidently assert

that they have always known something even if they first learned it from the

experimenter just moments earlier (M. Taylor, Esbensen, & Bennett, 1994).

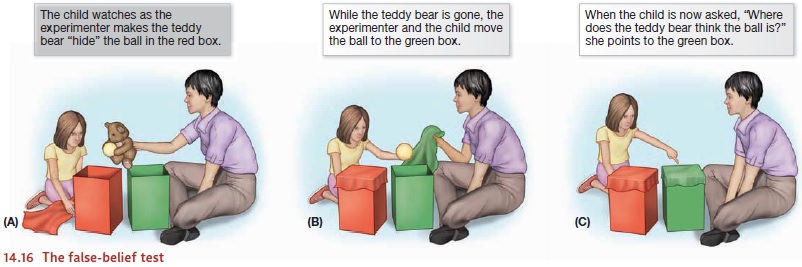

Another

limitation concerns the child’s understanding of false beliefs. According to

many authors, a 3-year-old does not understand that beliefs can be true or

false and that different people can have different beliefs. Evidence comes from

studies using false-belief tests (Wimmer & Perner, 1983; also Lang &

Perner, 2002). In a typical study of this kind, a child and a teddy bear sit in

front of two boxes, one red and the other green. The experimenter opens the red

box and puts a ball in it. He then opens the green box and shows the child—and

the bear—that this box is empty. The teddy bear is now taken out of the room

(to play for a while), and the experimenter and the child move the ball from

the red box into the green one. Next comes the crucial step. The teddy bear is

brought back into the room, and the child is asked, “Where will the teddy look

for the ball?” Virtually all 3-year-olds and some 4-year-olds will answer, “In

the green box.” If you ask them why, they will answer, “Because that’s where it

is.” It would appear, then, that these children do not really understand the

nature of belief. They seem to assume that their beliefs are inevitably shared

by others, and likewise, they seem not to under-stand that others might have

beliefs that are false (Figure 14.16).

However,

by age 4-1/2 or so, children get the idea that not all knowledge is shared. If

they are asked, “Where will the teddy look for the candy?” they will answer,

“He’ll look in the red box because that’s where he thinks the candy is” (H.

Wellman & Lagattuta, 2000; H. Wellman, Cross, & Watson, 2001). The

children now seem to have learned that different individuals have different

beliefs, and that one’s beliefs depend on access to the relevant information.

Related Topics