Chapter: Psychology: Development

Attachment - Socioemotional Development in Infancy and Childhood

ATTACHMENT

As

children start learning about the social world—developing expectations for how

others will behave and learning to “read” the signals that others provide—they

are also forming their first social relationship, with their primary caregiver,

usually the mother. This is evident in the fact that, when they are between 6

and 8 months old, infants begin to show a pattern known as separation anxiety, in

which they become visibly (and sometimes loudly) upset when their caregiver

leaves the room. This is a powerful indication that the infant has formed an attachment to the caregiver—a strong,

enduring, emotional bond.

This

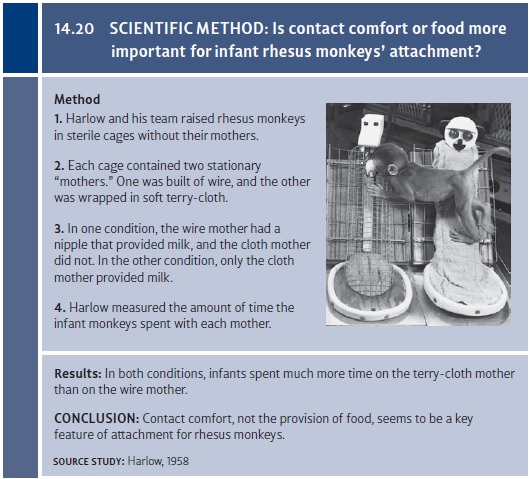

bond seems to grow out of the psychological comfort the mother provides the

infant. Evidence for this claim comes from many sources, including a series of

classic studies by Harry Harlow (1905–1981). Harlow (e.g., 1958) raised rhesus

monkeys with-out their mothers; each rhesus infant lived alone in a cage that

contained two station-ary figures, one built of wire and the other of soft

terry cloth. The wire figure was equipped with a nipple that yielded milk, but

the terry-cloth model had none. Which figure would the monkey infants

prefer—the one that provided nutrition, or the one that provided (what Harlow

called) “contact comfort”? In fact, the infants spent much

more

time on the terry-cloth “mother” than on the wire figure—especially when they

were frightened. When approached by a clanking mechanical toy, they invariably

rushed to the terry-cloth mother and clung tightly (Figure 14.20).

Is

comfort (and not nutrition) also the key for human attachment? British

psychia-trist John Bowlby argued forcefully that it is. In Bowlby’s view,

children become attached to a caregiver because this adult provides a secure base for the child, a

rela-tionship (and, for the young infant, a place)

in which the child feels safe and protected (Figure 14.21). The child uses the

secure base as a haven in times of threat, and, accord-ing to Bowlby, this

provides the child with the sense of safety that allows her to explore the

environment. The child is able to venture into the unknown, and explore, and

learn, because she knows that, if the going gets rough, she can always return

to the secure base (Waters & Cummings, 2000).

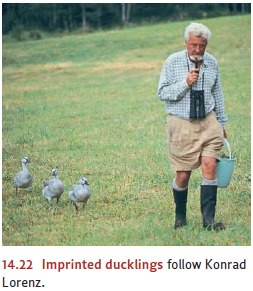

Bowlby

argued that this tendency to form attachments, and to rely on the

psycho-logical comfort of a secure base, is rooted in our evolutionary past,

and this is why we can easily find parallels to human attachment in other

species. For example, consider the process of imprinting, a kind of learning that, in many species, provides the

basis for an infant’s attachment to its mother (e.g., Lorenz, 1935). To take a

specific case, as soon as a duckling can walk (about 12 hours after hatching),

it will approach and fol-low virtually any moving stimulus. If the duckling

follows this moving object for about 10 minutes, an attachment is formed, and

the bird has now imprinted on this object. From this point forward, the

duckling will continue to follow the attachment object, show distress if

separated from it, and run to it in circumstances involving threat.

This

simple kind of learning is usually quite effective, since the first moving

stimu-lus a duckling sees is usually its mother. But imprinting can occur to

other objects, by accident or through an experimenter’s manipulations. In some

studies, ducklings have

been

exposed to a moving toy duck on wheels, or to a rectangle sliding back and

forth behind a glass window, or even to the researcher’s booted legs (Figure

14.22). In each case, the ducklings follow these objects as if following their

mother, uttering plaintive distress calls whenever the attachment object is not

nearby (E. H. Hess, 1959, 1973).

Do

human infants show a similar pattern of imprinting? Some studies have compared

the attachment of infants who had after-birth contact with their mothers to

those who did not (usually due to medical complications in either mother or

baby); the studies found little difference between the groups, and hence

provided no evidence for a specific period during which human newborns form

attachments (Eyer, 1992). Similarly, infants who must spend their initial days

with a nurse or in an incubator do not form a lasting attachment to either.

Clearly, then, the pattern of imprint-to-object-of-first-exposure, common in

many species, is not found in humans.

Even

with these differences between humans and other animals, the fact remains that

human infants form a strong attachment to a caregiver, usually the mother—

presumably because young children in most cultures spend the vast majority of

their time with their mothers (M. E. Lamb, 1987, 1997). What role does this

leave for the father? Infants do develop strong attachments to both parental

figures (Pipp, Easterbrooks, & Brown, 1993), but mothers and fathers

typically behave differently with their infant children, and there are

corresponding differences in attachment. Fathers tend to be more physical and

vigorous in their play, bouncing their children or tossing them in the air. In

contrast, mothers generally play more quietly with their chil-dren, telling

them stories or reciting nursery rhymes and providing hugs and caresses rather

than tumbles and bounces. The children act accordingly, tending to run to the

mother for care and comfort but to the father for active play (Figure 14.23;

Clarke-Stewart, 1978; M. E. Lamb, 1997; Parke, 1981).

Related Topics