Chapter: Psychology: Development

Physical and Sensorimotor Development in Infancy and Childhood

Physical and Sensorimotor Development in Infancy and

Childhood

The

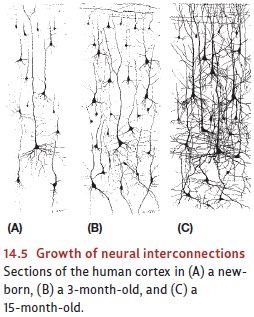

immaturity of the human infant is apparent if we examine the brain itself.

Figure 14.5 shows sections of the human cortex in a newborn, a 3-month-old, and

a 15-month-old child (Conel, 1939, 1947, 1955). Notice that the number of

neural interconnections

grows

tremendously during this period. Indeed, by one estimate, new neural

connec-tions are formed in the infant’s brain, and old ones removed, at an

astonishing rate of 100,000 per second (Rakic, 1995).

This

growth in brain size and complexity, and, indeed, growth in all aspects of the

child’s body, continues for many years, coming in spurts that each last a few

months. This pattern is obvious for growth of the body (Hermanussen, 1998) but

is also true for the child’s brain, with the spurts typically beginning around

ages 2, 6, 10, and 14 (H. T. Epstein, 1978). Each of these spurts leaves the

brain up to 10% heavier than it was when the spurt began (Kolb & Whishaw,

2009).

Even

at birth, the infant’s immature brain is ready to support many activities. For

exam-ple, infants’ senses function quite well from the start. Infants can

discriminate between tones of different pitch and loudness, and they show an

early preference for their mother’s voice over that of a strange female (Aslin,

1987; DeCasper & Fifer, 1980). Newborns’ vision is not yet fully developed.

Though quite near-sighted, newborns can see objects a foot or so away (the

distance to a nursing mother’s face) and readily discriminate brightness and

color, and they can track a moving stimulus with their eyes (Aslin, 1987;

Bornstein, 1985).

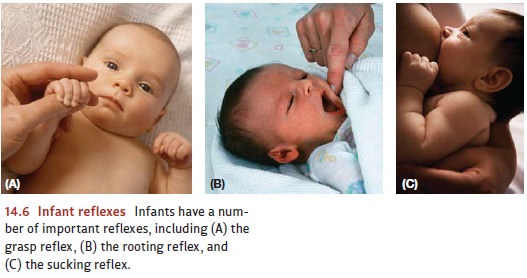

In

contrast to newborns’ relatively advanced sensory capacities, infants initially

have little ability to control their body movements. They thrash around

awkwardly and can-not hold up their heads. But they do have a number of

important reflexes (Figure 14.6), including the grasp reflex—when an object touches an infant’s palm, she closes

her fist tightly around it. If the object is lifted up, the infant hangs on and

is lifted along with it, supporting her whole weight for a minute or more.

Other

infantile reflexes pertain to feeding. For example, the rooting reflex refers to the fact that when a baby’s cheek is

lightly touched, the baby’s head turns toward the source of stimulation, his

mouth opens, and his head continues to turn until the stim-ulus (usually a

finger or nipple) is in his mouth. A related reflex, called the suckingreflex, then takes over and

leads the child to suck automatically on whatever is placedin his mouth.

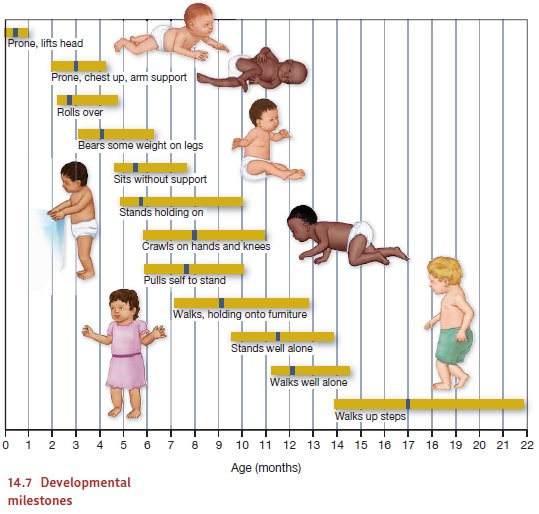

By

her first birthday, the child will have gained vastly better control over her

own actions, and this increase in skill continues over the next decade. These

skills emerge in an orderly progression, as shown in Figure 14.7. Infants first

learn to roll over (typically by 3 months), then to sit (usually by 6 months),

then to creep and then to walk (usually by 12 months). However, the ages

associated with these various achievements must be understood as rough

approximations, because there is variation from one infant to another and from

one culture to another. For example, the Kipsigis of Kenya begin training their

infants to stand and walk early on (Super, 1976), whereas the Ache of Paraguay

carry their children nearly everywhere, leading to delayed onset of walking

(Kaplan & Dove, 1987).

Related Topics