Chapter: Psychology: Development

Development of Moral Thinking - Socioemotional Development in Infancy and Childhood

THE DEVELOPMENT OF MORAL THINKING

One

last issue draws us back to the interplay between the child’s intellectual,

social, and emotional development. This is the issue of morality—and the

child’s growing sense of right and wrong. For many years, researchers framed

these issues in terms of claims offered by Lawrence Kohlberg. Kohlberg began

with data gathered with a simple method. He presented boys with stories that

posed moral dilemmas and questioned them about the issues these stories raised.

One often-quoted example is a story about a man whose wife would die unless

treated with a drug that cost far more money than the man had. The husband

scraped together all the money he could, but it was not enough, so he promised

the pharmacist that he would pay the balance later. The phar-macist still

refused to give him the drug. In desperation, the husband broke into the

pharmacy and stole the drug, and this led to the question for the research

participants: They were asked whether the husband’s actions were right or wrong

and why.

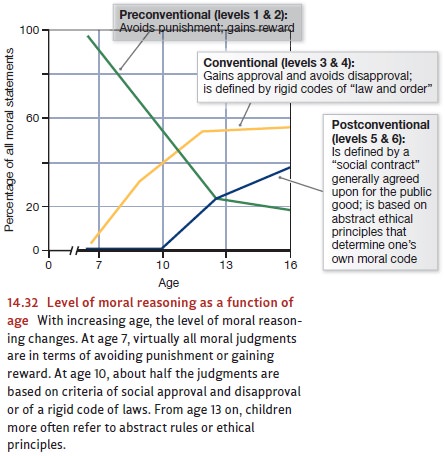

Kohlberg

posed this question and similar ones to boys of various ages. Based on their

answers, he concluded that moral reasoning develops through a series of three

broad levels; each level, in turn, is divided into an early stage and a late

stage, so that the entire conception contains six distinct stages. The first

pair of stages (and so the first level) relies on what Kohlberg calls preconventional reasoning—moral

judgments focused on getting rewards and avoiding punishment. A child at this

level might say, “If you let your wife die, you’ll get in trouble.” The second

pair of stages relies on conventional

reasoning and is centered on social relationships, conventions, andduties.

A response such as “Your family will think you’re bad if you don’t help your

wife” would be indicative of this type of reasoning. The final pair of stages

involves postconventional reasoning and

is concerned with ideals and broad moral principles:“It’s wrong to let somebody

die” (Figure 14.32).

Kohlberg intended his conception to describe all people, no matter who they are or where they live, but a number of scholars have challenged this claim. One set of con-cerns was raised by Carol Gilligan (1982), who argued that Kohlberg’s test did a better job of reflecting males’ moral reasoning than females’. In her view, men tend to see morality as a matter of justice, ultimately based on abstract, rational principles by which all individuals will end up being treated fairly. Women, in contrast, see morality more in terms of compassion, human relationships, and special responsibilities to those with whom one is intimately connected.

Gilligan’s

view certainly does not imply that one gender is less moral than the other. In

fact, studies of moral reasoning reveal no reliable sex differences on

Kohlberg’s test (Brabeck, 1983; L. J. Walker, 1984, 1995; but see Baumrind,

1986; L. J. Walker, 1989). Even with these demonstrations of gender equality,

though, the possibility remains that men and women do emphasize different

values in their moral reasoning—a claim that raises questions about the

universality of Kohlberg’s proposal.

A

similar critique focuses on cultural differences. A number of studies have

shown that when members of less technological societies are asked to reason

about moral dilemmas, they generally attain low scores on Kohlberg’s scale. They

justify acts on the basis of concrete issues, such as what neighbors will say,

or concern over one’s wife, rather than on more abstract conceptions of justice

and morality (Kohlberg, 1969; Tietjen & Walker, 1985; Walker & Moran,

1991; also see Rozin, 1999). This does not mean that the inhabitants of, say, a

small Turkish village are less moral than the residents of Paris or New York

City. A more plausible interpretation is that Turkish villagers spend their

lives in frequent face-to-face encounters with their community’s members. Under

the circumstances, they are likely to develop a more concrete morality that

gives the greatest weight to care, responsibility, and loyalty (Kaminsky, 1984;

Simpson, 1974). Given their circumstances, it is not clear that their concrete

morality should be considered—as Kohlberg did—a “lower” level of morality.

Even

acknowledging these points, there is clearly value in Kohlberg’s account.

Children do seem to progress through the stages he describes, so that there is

a strong correlation between a child’s age and the maturity of her moral

reasoning as assessed by Kohlberg’s procedure (Colby & Kohlberg, 1987).

Children also seem to move through these six stages in a sequence, just as

Kohlberg proposed (Colby & Kohlberg, 1987; Rest, Narvaez, Bebeau, &

Thomas, 1999). There also seems to be a link between a person’s moral maturity

(as assessed by Kohlberg) and the likelihood that he will actually behave

morally. In one study, college students were given an opportunity to cheat on a

test. Only 15% of the students who reasoned at a “postcon-ventional” level took

this opportunity, compared to 55% of the “conventional” stu-dents and 70% of

the “preconventional” students (Judy & Nelson, 2000; Kohlberg, Levine,

& Hewer, 1984).

Even

so, the relationship between someone’s capacity for moral reasoning and the

likelihood that he will behave morally is, at best, only moderate (Bruggeman

& Hart, 1996). This makes it clear that a number of other factors also

influence moral behavior in everyday life (Krebs & Denton, 2005).

Related Topics