Chapter: Psychology: Development

Differences in Attachment - Socioemotional Development in Infancy and Childhood

DIFFERENCES IN ATTACHMENT

Many

aspects of the attachment process are similar for all children. But we also

need to acknowledge that children differ in their patterns of attachment. To

study these differences, Mary Ainsworth and her colleagues developed a

procedure for assessing attachment—the so-called strange situation (Figure 14.24; Ainsworth & Bell, 1970;

Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978). In this procedure, the

12-month-old child is brought into an unfamiliar room that contains many toys

and is allowed to explore and play with the mother present. After a while, an

unfamiliar woman enters, talks to the mother, and then approaches the child.

The next step is a brief separation—the mother leaves the child alone with the

stranger. After a few minutes, the mother returns and the stranger leaves.

This

setting is mildly stressful for most children, and by observing how the child

handles the stress, Ainsworth argued that we can determine the nature of the

child’s attachment. Specifically, Ainsworth and subsequent researchers argued

that children’s behavior in this setting will fall into one of four categories.

First, children who are securely attached

will explore, play with the toys, and even make wary overtures to

thestranger, so long as the mother is present. When the mother leaves, these

infants will show minor distress. When she returns, they greet her with great

enthusiasm.

Other

children show patterns that Ainsworth regarded as signs of insecure attachment.

Some of these children are described as anxious/resistant.

They do not explore, even in the mother’s presence, and become quite upset when

she leaves. Upon reunion, they act ambivalent, crying and running to her to be

picked up, but then kick-ing or slapping her and struggling to get down. Still

other children show the third pattern, called anxious/avoidant. They are distant and aloof while the mother is

present,and, although they sometimes search for her in her absence, they

typi-cally ignore her when she returns.

Children

in the fourth category show an attachment pattern called disorganized (Main & Solomon, 1990). Children in this group

seem tolack any organized way for dealing with the stress they experience. In

the strange situation, they sometimes look dazed or confused. They show

inconsistent behaviors—for example, crying loudly while trying to climb into

their mothers’ laps. They seem distressed by their moth-ers’ absence, but

sometimes move away from her when she returns.

In

healthy, middle-class families, roughly 60% of the infants tested are

categorized as “secure,” 10% as “anxious / resistant,” 15% as “anxious

/avoidant,” and 15% as “disorganized” (van Ijzendoorn, Schuengel, &

Bakermans-Kranenburg, 1999). The proportion of chil-dren showing “secure”

attachment is lower in lower-income families and families in which there are

psychological or medical problems affecting either the parents or the children.

One study, for example, assessed children who were chronically undernourished;

only 7% of these were “securely attached” (Valenzuela, 1990, 1997). Likewise,

mothers who are depressed, neurotic, or anxious are less likely to have

securely attached infants (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1997).

Many

theorists argue that a child’s attachment status shapes his social world in

important ways. In part, this claim derives from the notion of a secure base: A securely attached child

feels safe, confident,

and

willing to take initiative in a wide range of circumstances, and these traits

will open a path to new experiences and new learning opportunities. Moreover,

securely attached children usually have a more harmonious relationship with

their caregivers and are therefore better able to learn from them; this, too,

can lead to numerous advantages in months and years to come (cf. Bretherton,

1990).

In

addition, Bowlby argued that the attachment relationship provides the child

with an internal working model of

the social world. This model includes a set of beliefs about how people behave

in social relationships, guidelines for interpreting others’ actions, and

habitual responses to make in social settings. This model grows out of the

child’s relationship with a caregiver, and according to Bowlby, it provides a

template that sets the pattern for other relationships, including friendships

and even romances. Thus, for example, if the child’s attachment figure is

available and responsive, the child expects future relationships to be

similarly gratifying. If the child’s attachment figure is unavailable and

insensitive, then the child develops low expectations for future relationships.

A

number of studies have demonstrated that these working models of attachment do

seem to have important consequences. For example, children who are securely

attached at 1 year of age are more attractive to other toddlers as playmates in

comparison to chil-dren who were insecurely attached (B. Fagot, 1997; Vondra,

Shaw, Swearingen, Cohen,

Owens,

2001; also B. Schneider, Atkinson, & Tardif, 2001; R. A. Thompson, 1998,

1999). Likewise, children who were securely attached show more helping and

concern for peers (van IJzendoorn, 1997; also see DeMulder, Denham, Schmidt,

& Mitchell, 2000). Even more impressive, children who were securely

attached as infants are more likely, as teenagers, to have close friends

(Englund, Levy, Hyson, & Sroufe, 2000; Feeney & Collins, 2001; Shulman,

Elicker, & Sroufe, 1994) and are less likely to suffer from anxiety disorders

in childhood and adolescence (Warren, Huston, Egeland, & Sroufe, 1997).

Unmistakably,

then, a child’s attachment pattern when he is 1 year old is a powerful

predictor of things to come in that child’s life. But what is the mechanism

behind this linkage? Bowlby argued that secure attachment leads to an internal

working model that helps the child in subsequent relation-ships. If this is

right, then secure attachment is associated with later positive outcomes because

the attachment is what produces these

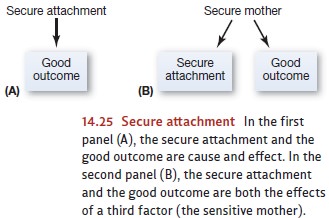

outcomes, as depicted in Figure 14.25A. However, other interpretations of the

data are possible. Imagine, for example, that a child has a sensitive and

supportive caregiver. This could lead both to secure attachment and to better adjustment later on. In

this case, too, we would expect secure attachment to be associated with good

adjustment later in life— but not because the attachment caused the later

adjustment; instead, they could be two different effects of a single cause

(Figure 14.25B).

The

cause-and-effect story is further complicated by the fact that someone’s

attach-ment pattern can change. Overall, attachment patterns tend to be

consistent from infancy all the way to adulthood (Fraley, 2002)—and so, for

example, a child who seems securely attached when first tested is likely to be

classified the same way when assessed months (or even years) later. Even so,

they may change, especially if there is an important change in the child’s

circumstances, like a parent losing a job or becoming ill. Thus, even if the

1-year-old’s attachment pattern does create a trajectory likely to shape the

child’s life, there is nothing inevitable about that trajectory, and this, too,

must be acknowledged when we try to think through how (or whether) a young

child’s attach-ment will shape life events in years to come (R. A. Thompson,

2000, 2006).

Related Topics