Chapter: Security in Computing : Security in Networks

Strong Authentication and Kerberos - Security in Networks

Strong Authentication

As we have seen in earlier

chapters, operating systems and database management systems enforce a security

policy that specifies whowhich individuals, groups, subjectscan access which resources

and objects. Central to that policy is authentication: knowing and being

assured of the accuracy of identities.

Networked environments need

authentication, too. In the network case, however, authentication may be more

difficult to achieve securely because of the possibility of eavesdropping and

wiretapping, which are less common in nonnetworked environments. Also, both

ends of a communication may need to be authenticated to each other: Before you

send your password across a network, you want to know that you are really

communicating with the remote host you expect. Lampson [LAM00] presents the problem of authentication in

autonomous, distributed systems; the real problem, he points out, is how to

develop trust of network entities with which you have no basis for a

relationship. Let us look more closely at authentication methods appropriate

for use in networks.

One-Time Password

The wiretap threat implies

that a password could be intercepted from a user who enters a password across

an unsecured network. A one-time password can guard against wiretapping and

spoofing of a remote host.

As the name implies, a one-time password is good for one use

only. To see how it works, consider the easiest case, in which the user and

host both have access to identical lists of passwords, like the one-time pad

for cryptography from Chapter 2. The

user would enter the first password for the first login, the next one for the

next login, and so forth. As long as the password lists remained secret and as

long as no one could guess one password from another, a password obtained

through wiretapping would be useless. However, as with the one-time

cryptographic pads, humans have trouble maintaining these password lists.

To address this problem, we

can use a password token, a device

that generates a password that is unpredictable but that can be validated on

the receiving end. The simplest form of password token is a synchronous one,

such as the SecurID device from RSA Security, Inc. This device displays a

random number, generating a new number every minute. Each user is issued a

different device (that generates a different random number sequence). The user

reads the number from the device's display and types it in as a one-time

password. The computer on the receiving end executes the algorithm to generate

the password appropriate for the current minute; if the user's password matches

the one computed remotely, the user is authenticated. Because the devices may

get out of alignment if one clock runs slightly faster than the other, these

devices use fairly natural rules to account for minor drift.

What are the advantages and

disadvantages of this approach? First, it is easy to use. It largely counters

the possibility of a wiretapper reusing a password. With a strong

password-generating algorithm, it is immune to spoofing. However, the system

fails if the user loses the generating device or, worse, if the device falls

into an attacker's hands. Because a new password is generated only once a

minute, there is a small (one-minute) window of vulnerability during which an

eavesdropper can reuse an intercepted password.

ChallengeResponse Systems

To counter the loss and reuse

problems, a more sophisticated one-time password scheme uses challenge and

response, as we first studied in Chapter 4. A challenge and response device looks like a simple

pocket calculator. The user first authenticates to the device, usually by means of a PIN. The remote

system sends a random number, called the "challenge," which the user

enters into the device. The device responds to that number with another number,

which the user then transmits to the system.

The system prompts the user

with a new challenge for each use. Thus, this device eliminates the small

window of vulnerability in which a user could reuse a time-sensitive

authenticator. A generator that falls into the wrong hands is useless without

the PIN. However, the user must always have the response generator to log in,

and a broken device denies service to the user. Finally, these devices do not

address the possibility of a rogue remote host.

Digital Distributed Authentication

In the 1980s, Digital

Equipment Corporation recognized the problem of needing to authenticate

nonhuman entities in a computing system. For example, a process might retrieve

a user query, which it then reformats, perhaps limits, and submits to a

database manager. Both the database manager and the query processor want to be

sure that a particular communication channel is authentic between the two.

Neither of these servers is running under the direct control or supervision of

a human (although each process was, of course, somehow initiated by a human).

Human forms of access control are thus inappropriate.

Digital [GAS89, GAS90]

created a simple architecture for this requirement, effective against the

following threats:

·

impersonation of a server by a rogue

process, for either of the two servers involved in the authentication

·

interception or modification of data exchanged between servers

·

replay of a previous authentication

The architecture assumes that

each server has its own private key and that the corresponding public key is

available to or held by every other process that might need to establish an

authenticated channel. To begin an authenticated communication between server A

and server B, A sends a request to B, encrypted under B's public key. B

decrypts the request and replies with a message encrypted under A's public key.

To avoid replay, A and B can append a random number to the message to be

encrypted.

A and B can establish a private

channel by one of them choosing an encryption key (for a secret key algorithm)

and sending it to the other in the authenticating message. Once the

authentication is complete, all communication under that secret key can be

assumed to be as secure as was the original dual public key exchange. To

protect the privacy of the channel, Gasser recommends a separate cryptographic

processor, such as a smart card, so that private keys are never exposed outside

the processor.

Two implementation

difficulties remain to be solved: (a) How can a potentially large number of

public keys be distributed and (b) how can the public keys be distributed in a

way that ensures the secure binding of a process with the key? Digital

recognized that a key server (perhaps with multiple replications) was necessary

to distribute keys. The second difficulty is addressed with certificates and a

certification hierarchy, as described in Chapter 2.

Both of these design

decisions are to a certain degree implied by the nature of the rest of the

protocol. A different approach was taken by Kerberos, as we see in the

following sections.

Kerberos

As we introduced in Chapter 4, Kerberos is a system that supports

authentication in distributed systems. Originally designed to work with secret

key encryption, Kerberos, in its latest version, uses public key technology to

support key exchange. The Kerberos system was designed at Massachusetts

Institute of Technology [STE88, KOH93].

Kerberos is used for

authentication between intelligent processes, such as client-to-server tasks,

or a user's workstation to other hosts. Kerberos is based on the idea that a

central server provides authenticated tokens, called tickets, to requesting applications. A ticket is an unforgeable,

nonreplayable, authenticated object. That is, it is an encrypted data structure

naming a user and a service that user is allowed to obtain. It also contains a

time value and some control information.

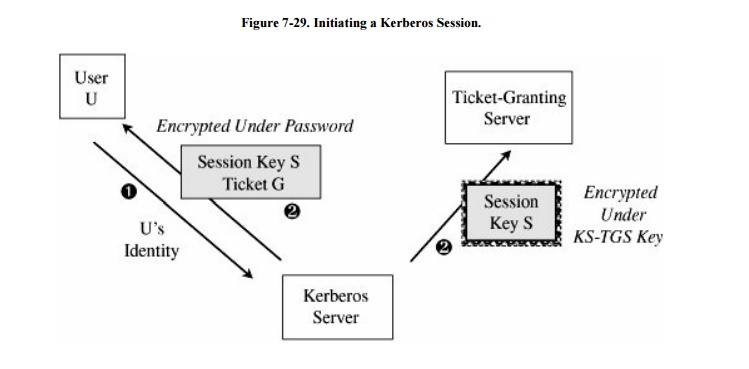

The first step in using

Kerberos is to establish a session with the Kerberos server, as shown in Figure 7-29. A user's workstation sends the

user's identity to the Kerberos server when a user logs in. The Kerberos server

verifies that the user is authorized. The Kerberos server sends two messages:

to the user's workstation, a session key SG for use in communication with the ticket-granting server (G) and a ticket TG for the ticket-granting server; SG is encrypted under the user's password: E(SG + TG, pw)

to the ticket-granting server, a copy of the session key SG and the identity of the user (encrypted under a key shared between the Kerberos server and the ticket-granting server)

If the workstation can decrypt E(SG

+ TG, pw) by using pw, the password typed by the user, then the user

has succeeded in an authentication with the workstation.

Notice that passwords are stored at the

Kerberos server, not at the workstation, and that the user's password did not

have to be passed across the network, even in encrypted form. Holding passwords

centrally but not passing them across the network is a security advantage.

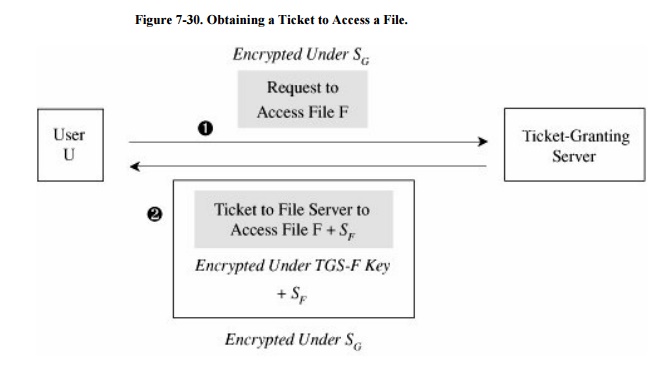

Next, the user will want to exercise some other

services of the distributed system, such as accessing a file. Using the key SG

provided by he Kerberos server, the user U requests a

ticket to access file F from the ticket-granting server. As shown in Figure 7-30, after the ticket-granting server

verifies U's access permission, it returns a ticket and a session key. The

ticket contains U's authenticated identity (in the ticket U obtained from the

Kerberos server), an identification of F (the file to be accessed), the access

rights (for example, to read), a session key SF for the file server

to use while communicating this file to U, and an expiration date for the

ticket. The ticket is encrypted

under a key shared

exclusively between the ticket-granting server and the file server. This ticket

cannot be read, modified, or forged by the user U (or anyone else). The

ticket-granting server must, therefore, also provide U with a copy of SF, the session key for the

file server.

Requests for access to other

services and servers are handled similarly.

Kerberos was carefully

designed to withstand attacks in distributed environments:

·

No passwords communicated on the network. As already described, a

user's password is stored only at the Kerberos server. The user's password is

not sent from the user's workstation when the user initiates a session.

(Obviously, a user's initial password must be sent outside the network, such as

in a letter.)

·

Cryptographic protection against spoofing. Each access request is

mediated by the ticket-granting server, which knows the identity of the

requester, based on the authentication performed initially by the Kerberos

server and on the fact that the user was able to present a request encrypted

under a key that had been encrypted under the user's password.

·

Limited period of validity. Each ticket is issued for a limited

time period; the ticket contains a timestamp with which a receiving server will

determine the ticket's validity. In this way, certain long-term attacks, such

as brute force cryptanalysis, will usually be neutralized because the attacker

will not have time to complete the attack.

·

Timestamps to prevent replay attacks. Kerberos requires reliable

access to a universal clock. Each user's request to a server is stamped with

the time of the request. A server receiving a request compares this time to the

current time and fulfills the request only if the time is reasonably close to

the current time. This time-checking prevents most replay attacks, since the

attacker's presentation of the ticket will be delayed too long.

·

Mutual authentication. The user of a service can be assured of any

server's authenticity by requesting an authenticating response from the server.

The user sends a ticket to a server and then sends the server a request

encrypted under the session key for that server's service; the ticket and the

session key were provided by the ticket-granting server. The server can decrypt

the ticket only if it has the unique key it shares with the ticket-granting

server. Inside the ticket is the session key, which is the only means the

server has of decrypting the user's request. If the server can return to the

user a message encrypted under this same session key but containing 1 + the

user's timestamp, the server must be authentic. Because of this mutual

authentication, a server can provide a unique channel to a user and the user

may not need to encrypt communications on that channel to ensure continuous

authenticity. Avoiding encryption saves time in the communication.

Kerberos is not a perfect

answer to security problems in distributed systems.

· Kerberos requires continuous availability of a

trusted ticket-granting server. Because the ticket-granting server is the basis

of access control and authentication, constant access to that server is

crucial. Both reliability (hardware or software failure) and performance

(capacity and speed) problems must be addressed.

· Authenticity of servers requires a trusted

relationship between the ticket-granting server and every server. The

ticket-granting server must share a unique encryption key with each

"trustworthy" server. The ticket-granting server (or that server's

human administrator) must be convinced of the authenticity of that server. In a

local environment, this degree of trust is warranted. In a widely distributed

environment, an administrator at one site can seldom justify trust in the

authenticity of servers at other sites.

Kerberos requires timely

transactions. To prevent replay attacks, Kerberos limits the validity of a

ticket. A replay attack could succeed during the period of validity, however.

And setting the period fairly is hard: Too long increases the exposure to

replay attacks, while too short requires prompt user actions and risks

providing the user with a ticket that will not be honored when presented to a

server. Similarly, subverting a server's clock allows reuse of an expired

ticket.

·

A subverted workstation can save and later replay user passwords.

This vulnerability exists in any system in which passwords, encryption keys, or

other constant, sensitive information is entered in the clear on a workstation

that might be subverted.

·

Password guessing works. A user's initial ticket is returned under

the user's password. An attacker can submit an initial authentication request

to the Kerberos server and then try to decrypt the response by guessing at the

password.

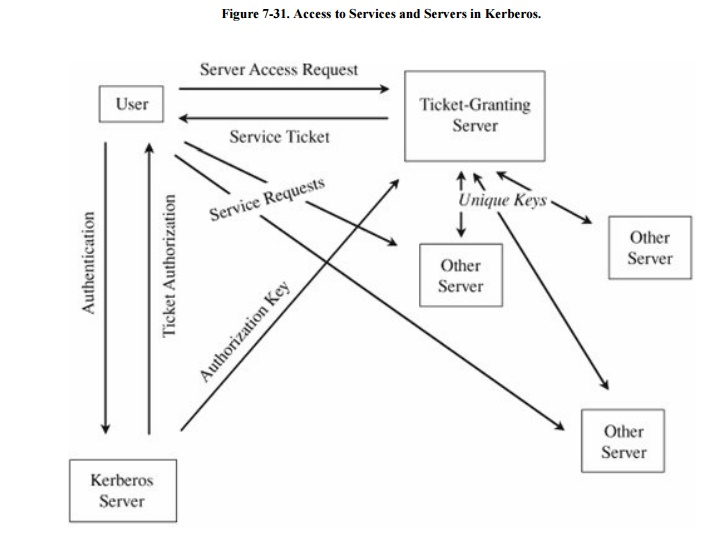

·

Kerberos does not scale well. The architectural model of Kerberos,

shown in Figure 7-31, assumes one

Kerberos server and one ticket-granting server, plus a collection of other

servers, each of which shares a unique key with the ticket-granting server.

Adding a second ticket-granting server, for example, to enhance performance or

reliability, would require duplicate keys or a second set for all servers.

Duplication increases the risk of exposure and complicates key updates, and

second keys more than double the work for each server to act on a ticket.

·

Kerberos is a complete solution. All applications must use Kerberos

authentication and access control. Currently, few applications use Kerberos

authentication, and so integration of Kerberos into an existing environment

requires modification of existing applications, which is not feasible.

Related Topics