Chapter: Psychology: Development

Piaget ’S Stage Theory

PIAGET

’S STAGE THEORY

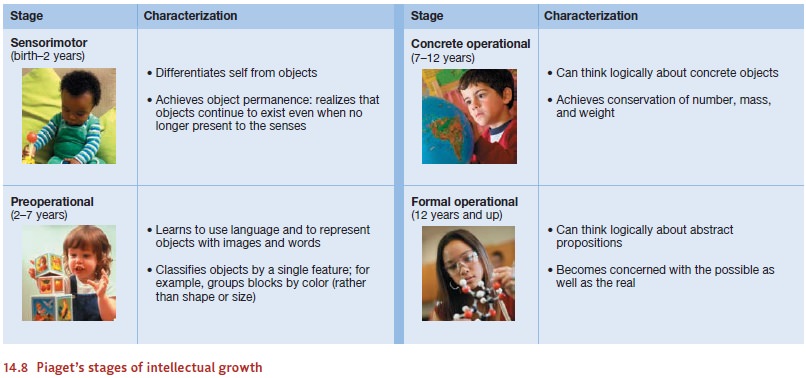

According

to Piaget, the child relies on a different type

of thinking than an adult does. In Piaget’s view, adult thinking emerges only

after the child has moved through a series of stages of intellectual growth

(Figure 14.8). They are the sensorimotor

period (from birth to about 2 years), the preoperational period (roughly 2 to 7 years), the concrete operational period (7 to 12

years), and the formal operational period

(approximately 12 years and up).

During

the sensorimotor period, Piaget

argued, the infant’s world consists of his own sensations. Therefore, when an

infant looks at a rattle, he is aware of looking at the rattle but has no

conception of the rattle itself existing as a permanent, independent object. If

the infant looks away from the rattle (and thus stops seeing it), then the

rat-tle ceases to exist. It is not just “out of sight, out of mind”—it is “out

of sight, out of existence.” In this way, Piaget claimed, infants lack a sense

of object permanence—the

understanding that objects exist independent of our momentary sensory or

motoric interactions with them.

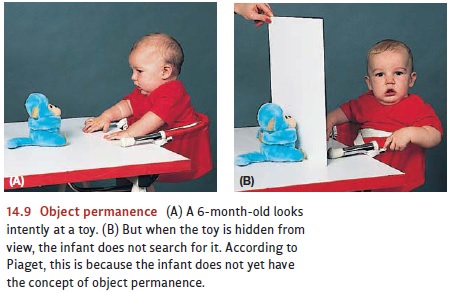

Piaget

developed this view based on his observation that infants typically look at a

new toy with delight, but if the toy disappears from view, they show little

concern (Figure 14.9). At a slightly later age, infants might show signs of

distress when the toy disappears, but they still make no effort to retrieve it.

This is true even if it seems perfectly obvious where the toy is located. For

example, an experimenter might drape a light cloth over the toy while an infant

is watching. In this situation, the toy is still easily within reach and its

shape is still (roughly) visible through the folds of the cloth. The child

watched it being covered just moments earlier. But still the infant makes no effort

to retrieve it.

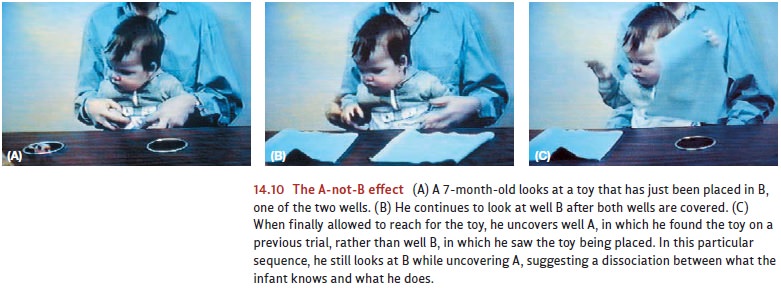

At about 8 months, infants do start to search for toys that have been hidden, but even then, their searching shows a peculiar limitation. Suppose, that a 9-month-old sees an experimenter hide a toy monkey under a cover located, say, to the child’s right. The child will happily push the cover off and snatch up the monkey. The experimenter now repeats the process a few times, always hiding the monkey under the same cover to the child’s right. Again and again the child pulls the cover off and retrieves the monkey. But now the experimenter changes the procedure slightly. Very slowly and in full view of the child, she hides the toy in a different place, say, under a cover to the child’s left. The child closely watches her every movement—and then does exactly what he did before. He searches under the cover on the right, even though he saw the experimenter hide the toy in another place just a moment earlier.

This

phenomenon is often called the A-not-B

effect, where A designates the

place where the object was first hidden and B

the place where it was hidden last (Figure 14.10). Why does this peculiar error

occur? Piaget (1952) argued that the 9-month-old still has not grasped the fact

that an object’s existence is independent of his own actions. Thus, the child

believes that his reaching toward place A (where he found the toy previously)

is as much a part of the monkey as the monkey’s tail is. In effect, then, the

child is not really searching for a monkey; he is searching for

the-monkey-that-I-find-on-the-right. No wonder, there-fore, that the child

continues searching in the same place.

According

to Piaget, a major accomplishment of the sensorimotor period is coming to

understand that objects exist on their own—even when they are not reached for,

seen, heard, or felt. Piaget held that what makes this accomplishment possible

is the infant’s increasingly sophisticated schemas—ways

of interacting with the world and (at a later stage of development) ways of

interacting with ideas about the

world.

Piaget

believed that newborns start life with very few schemas, and these tend to

involve the infant’s built-in reactions, such as sucking or grasping. In

Piaget’s view, these action pat-terns provide the infant’s only means of

responding to the world, and thus they provide the first mental categories

through which infants organize their world. Infants understand the world, in

other words, as consisting of the suckables, the graspables, and so on.

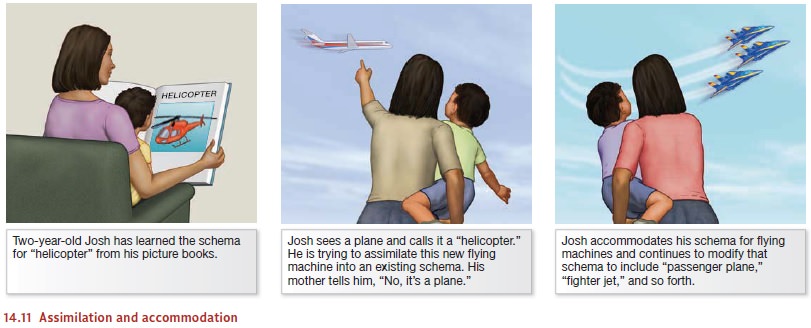

Across

the first few months of life, though, the child refines and extends these

schemas and learns how to integrate them into more complex ways of dealing with

the world. This evolution, according to Piaget, depends on two processes that

he claimed were responsible for all cognitive development: assimilation and

accommodation. In the process of assimilation,

children use the mental schemas they have already formed to interpret (and act

on) the environment; in other words, they assimilate objects in the environment

into their existing schemas. In the process of accommodation, the child’s schemas change as a result of his

experiences interacting with the world; that is, the schemas accommodate to the

environment (Figure 14.11).

Through

the processes of assimilation and accommodation, the child refines and

differentiates her schemas, which gradually leads her to create a range of new

schemas that enhance her ability to interact with the world. In addition, as

the child becomes increasingly skilled at using schemas, she eventually becomes

able to use more than one schema at a time—reaching while looking, grasping

while sucking. Coordinating these individual actions into one unified

exploratory schema helps to break the connection between an object and a

specific way of acting on or experiencing that object. This liberation of the

object from a specific action, in turn, helps propel the child toward

understanding the object’s independent existence—that is, it helps propel her

toward object permanence and a mature understanding of what an object is.

Piaget

believed that the sensorimotor period ends when children achieve object

per-manence (and, thus, the capacity for representational thought) at roughly 2

years of age. But, even so, the mental world of 2-year-olds is, in Piaget’s

view, a far cry from the world of adults. This is because 2-year-olds have not

yet learned how to interrelate their

mental representations in a coherent way. Piaget referred to the manipulation

of men-tal representations as operations,

and thus dubbed the period from age 2 to 7, before these mental operations are

evident, as the preoperational period.

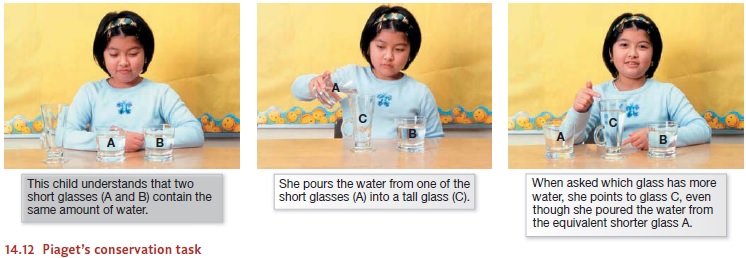

A

revealing example of preoperational thought is the young child’s apparent

failure to conserve quantity. One procedure demonstrating this failure uses two

identical glasses, A and B, which stand side by side and are filled with the

same amount of liq-uid. The experimenter then asks the child whether there is

more liquid in one glass or the other, then obligingly adds a drop here, a drop

there until the child is completely satisfied that there is “the same to drink

in this glass as in that.”

The

next step involves a new glass, C, which is taller but narrower than A and B

(Figure 14.12). While the child is watching, the experimenter pours the entire

contents of glass A into glass C. She then points to B and C and asks, “Is

there more in this glass or in that, or are they the same?” To an adult, the

amounts are obviously identical, since A was completely emptied into C, and A

and B were made equal at the outset. But 4- or 5-year-olds insist that there is

more liquid in C. When asked for their reason, they explain that the liquid

comes to a much higher level in C. They seem to think that the amount has

increased as it was transferred from one glass to another. They are too

impressed by the visible changes in liquid level to realize that the amount

nonetheless remains constant.

In

the preoperational period, children also fail tests that depend on the

conservation of number. In one such test, the experimenter first shows the

child two rows of pennies, and the child agrees that both rows contain the same

number of coins. The experimenter then rearranges one row by spacing the

pennies farther apart. Prior to age 5 or 6, chil-dren generally assert that

there are now more coins in this row because “they’re more spread out.” But

from about age 6 on, the child has no doubt that there are just as many coins

in the tightly spaced row as there are in the spread-out line.

Why

do preschool children fail to conserve? According to Piaget, part of the

problem is their inability to interrelate the different dimensions of a

situation. To conserve liquid quantity, for example, the children must first

comprehend that there are two relevant factors: the height of the liquid

column, and the width of the glass. They must then appreciate that a decrease

in the column’s height is accompanied by an increase in its width. Thus, the children

must be able to attend to both dimensions simultaneously and relate the

dimensions to each other. They lack this capacity, since it requires using a

higher-order schema to combine initially discrete aspects of a percep-tual

experience into one conceptual unit.

By

age 7 or so, once children have learned how to interrelate their mental

represen-tations, they enter the concrete

operational period. They now grasp the fact that changes in one aspect of a

situation can be compensated for by changes in some other aspect. They are also

able to transform their own mental representations in a variety of ways and

thus understand, for example, what would happen if the liquid were poured back

into its original glass. But according to Piaget, children’s intellectual

capacities are still limited in an important way: They can apply their mental

operations only to con-crete objects or events (hence the term concrete operations). It is not until

age 11 or 12 that formal operations are possible, and we will consider this

stage in the following sec-tion on adolescence.

Related Topics