Chapter: The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution, and Ecology: A history of fishes

Class Placodermi - Gnathostomes: early jawed fishes

Class Placodermi

Placoderms (“plate-skinned”) had tremendous success and diversity. Their name refers to the peculiar bony, often ornamented, plates that covered the anterior 30–50% of the body. Most placoderms had depressed, even flattened bodies, suggesting benthic existence. They may have preyed upon, and eventually replaced, pteraspidiform and cephalaspidiform fishes. As in ostracoderms, placoderms occurred first in marine habitats but later moved into fresh water. As in both ostracoderms and acanthodians (see next section), many placoderm groups show an evolutionary trend toward reduction in external armor, leading to a mobile existence in the water column. Placoderms had ossified haemal and neural arches along the unconstricted notochord and three semicircular canals. Placoderms arose in the Late Silurian, flourished worldwide in the Devonian, and disappeared by the Early Carboniferous. Their disappearance often correlates with the proliferation of chondrichthyans at the end of the Devonian, and ecological replacement is suspected.

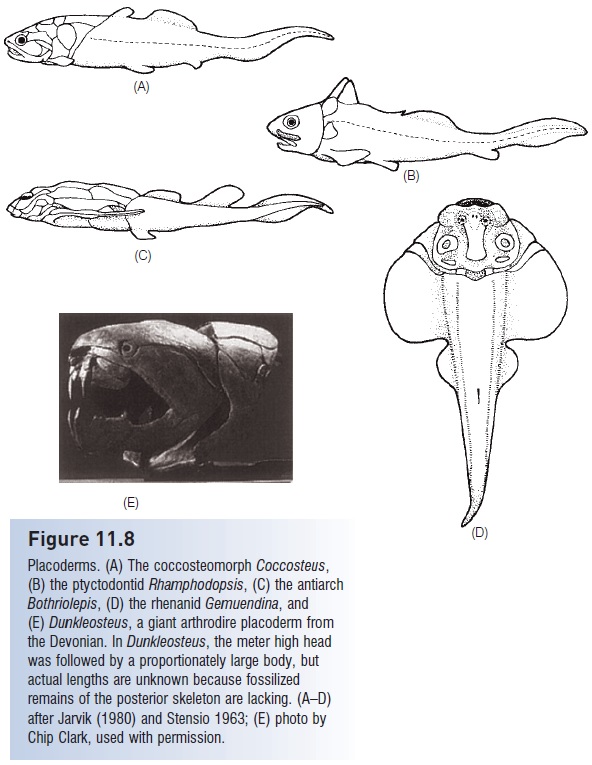

Six orders, 25–30 families, and perhaps 200 genera of placoderms are recognized (Fig. 11.8). Acanthothoraciformes from the Lower Devonian are the basal group and are therefore the oldest known jawed vertebrates. Arthrodiriforms (arthrodires, “jointed neck”) are the largest order, containing about 170 genera. They possessed a unique hinge at the back top of the head between the braincase and the cervical vertebrae, termed the craniovertebral joint. This joint allowed opening of the mouth by both dropping the lower jaw and raising the skull roof, thus increasing gape size. As the group evolved, this joint became larger and more elaborate, and dentition diversified into slashing, stabbing, and crushing structures. Arthrodires were among the largest of the placoderms. Dunkleosteus (Fig. 11.8E) was perhaps 6 m long, with a head more than 1 m high; some fossils suggest Dunkleosteus may have reached twice that size (Young 2003). Their large size and impressive dentition implicate the arthrodires as major predators of Devonian seas. Devonian arthrodires (e.g., Groenlandaspis) have also been found with fossilized silver and red pigment cells distributed in a pattern indicative of countershaded coloration. Red pigment cells suggest that color vision had already evolved in fishes more than 350 mybp

(Parker 2005).

None of the other placoderm orders attained the success of the arthrodires. Rhenaniforms were extremely dorsoventrally depressed and bore a striking resemblance to modern skates, rays, and angel sharks (e.g., Gemuendina, Fig. 11.8D), although their lateral fins were too heavily armored to be undulated or fl apped in the manner characteristic of modern skates and rays. The antiarchiforms (antiarchs, e.g., Bothriolepis, Fig. 11.8C) were predominantly freshwater, heavily armored, benthic fishes with a spiral valve intestine and jointed, arthropod-like pectoral appendages that had internal muscularization. Ptyctodontiforms greatly

Figure 11.8

Placoderms. (A) The coccosteomorph Coccosteus, (B) the ptyctodontid Rhamphodopsis, (C) the antiarch Bothriolepis, (D) the rhenanid Gemuendina, and (E) Dunkleosteus, a giant arthrodire placoderm from the Devonian. In Dunkleosteus, the meter high head was followed by a proportionately large body, but actual lengths are unknown because fossilized remains of the posterior skeleton are lacking. (A–D) after Jarvik (1980) and Stensio 1963; (E) photo by Chip Clark, used with permission.

Although the craniovertebral joint of many placoderms afforded increased jaw mobility compared to forms with a fixed upper jaw, placoderms lacked replacement dentition. Placoderm “teeth” consisted of dermal bony plates made up of a unique dentinelike material attached to jaw cartilage. This bone was often differentiated into sharp edges and points, producing “fearsome blade-like jawbones, which wore away during growth like self-sharpening scissors, to leave a hardened core forming massive stabbing blades” (Young 2003, p. 988). However, these blades were subject to breakage and wear, with no apparent repair or replacement mechanism. Placoderm jaw morphology and hinging also prohibited them from developing suction forces when feeding. The innovations of serially replaced teeth and of jaws that could create suction characterize the fish taxa that evidently replaced the placoderms and acanthodians.

Related Topics